National Issues

007 and the Search for Sani Yusuf Sada’s “A Lookout For Sunrise” -By Odia Ofeimun

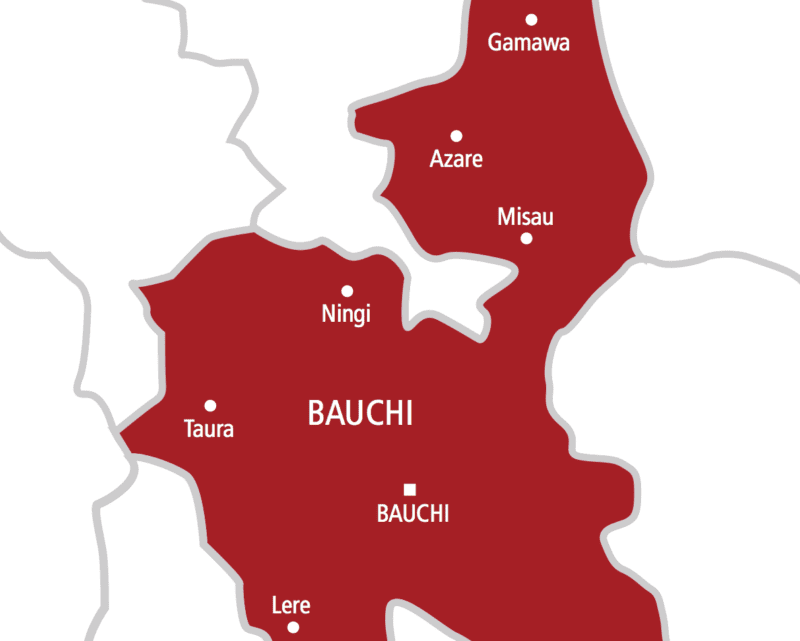

I could have proffered all that I have written so far on the first day after I met S.Y. (as all his friends called him). Our meeting was the kind that fate arranges with a certain formulaic zeal. It took place in the last quarter of 1975 in his hometown, Kankia, 58 kilometres to Katsina and 113 to Kano, where I had my primary assignment in the National Youth service Corps as Assistant Divisional Officer (ADO) in the office of the Divisional Secretary, overlooking the Divisional Council Chambers where I first met his grandfather, who was the District Head. There was something of a quiet solidity to the oldman which differentiated him from the vibrant Disrict Head of Musawa, the chair of the Council, who happened to be the father of the radical Marxist historian, Bala Usman, with whom I had opportunities to interact a number of times during the service year.

No poet I know writes like Sani Yusuf Sada (S.Y. for short). But he writes like every serious poet I have known – with a keen sense of the extraordinary truth and beauty of everyday life. This is a pointer to his uniqueness and the source of the fascination that his poetry must have for every serious lover of poetry who has encountered his works. His poems are finely honed vignettes with a complexity that derives from the very simplicity that freights his images. It is the kind of simplicity so many poets strive for but few achieve. Not for him the ‘educated’ lingo that forgets the source of experience in the everyday reality of our lives. He noses for the unspoken truth in personal relationships, the direness of power and the nemesis to come that will overtake those who do not have fellow-feeling as a standard of judgement. Whether in the English of the rostrum or classroom, pidgin of the streets and marketplace, or the occasional Hausa poem, S.Y. mesmerises by the sheer naturalness of his engagement with the world that is around and in all of us.

I account it a special duty and a matter of pride to identify with his poetry because I cannot forget how we met, struggled together as budding poets, and how, before he died, he fought valiantly to transcend the fear of drowning in either the maw of tradition or the silence that was overcoming a country in the grip of military dictatorship. Somehow, whatever was going right or wrong in his life, he never abandoned his poetry. It was part of the equipment with which he coped with a world made up of too many restraints in the form of a mis-primed religious conservatism, the ill-humour of political traditionalism and the insensate disregard for fellow human beings that mangled normal everyday interaction and stifled creativity and the love of progress that he could see among common people everywhere. His was a reaching for expressiveness in the tradition of the radical and revolutionary politics of the Aminu Kano School. Not in its more political fire-eating variety.

In the circumstance of a very conservative Northern Nigeria, he belonged to a new generation that exuded a rigorous sense of equality, ineffably. And, not as a put-on. No. It was the very fibre of his psychological make-up; rather free-wheeling, yes, in the sense that it was not formally anchored on a religious or political ideology. But it was a bid for the youth of the North to express themselves in modernist terms without making progress an antinomy of religious piety or political loyalty. For this, he relied on a good ear for the humour of the ordinary people in neighbourhoods across the districts and cityscapes of Nigeria who were irked immensely by unproductive social restraints. He stood to his full height, morally, as a man possessed by a capacity for empathy, relishing, with extraordinary vigour, a need for sharing in the lives of not only those one may regard as his own but total strangers. The most salutary part of this was that he did not need to prove his Northern-ness in order to be adjudged culturally or politically correct. He was unobtrusively a man of spare habits, who made no big deal about life-style. He took people as they came and made no apologies for his own ways and views.

My encounters with Bala Usman were, in themselves, something of an introduction to the overarching cultural and ideological atmosphere that produced the poet I was yet to meet. We met eventually when he was visiting his hometown, Kankia, from his own primary assignment in Lagos, my famous city by the lagoon, where I had worked as petrol attendant, factory labourer and clerical officer before going to the University.

In his poetry, the truth of life as he saw and wove it across several incidents and issues, is intoned to create the peculiar beauty of Pax Nigeriana. He was irremediably, unapologetically, committed to it. From an uncanny ability to see beyond, while savouring, the rampart diversity of Nigerian life, he sought always to appreciate the ordinariness and commonality across the differences. Across the diverse cultures that may appear to be grating against one another, he was very sensitive to the common need for fellow-feeling and the spoken or unspoken search for an assured sense of belonging within and between communities. As a youth of the sixties and seventies, a period in national life heady with a certain easy luxuriation in the feel-good atmosphere of the oil-boom days, he was tripped by nationalism of the post-civil war era which said ‘Never-Again’ when confronted by the kind of gross sassiness that once led to war. He did not mind the ambiance of the preachy form of national unity so long as it did not devalue the peace that had been bought with so much bloodshed in 30 months of carnage. For him, education, and the upswing of radical ideas across Nigerian universities was the true touchstone for rejuvenating the nation.

Resistance to the militariat was a form of idealism that he endorsed in the spirit of the old Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU) that cantered across to the rhetoric of the People’s Redemption Party (PRP). Thankfully, like all true poets, he always managed to see beyond the political moment. He saw through the slogans and therefore always managed to humanise them to the point of ritually discarding them in mock heroics when they failed to serve the purpose of standing by the lived experience of the ordinary talakawa for whom the slogans were hatched. His poetry never failed, for this reason, to immerse itself in the very thought processes of those living under the boot of the minders of the system. His identification with the poor and the neglected underclass across Nigerian society was not based on wanting to reduce everything to the measure of their humble status but wishing for a higher ground, a raising of the people to a height that made it possible to see progress, Nasara, as a rendezvous of equal citizens able to speak for themselves. Howbeit, his poetry had to speak for those who could not speak for themselves.

It may sound rather abrupt to say so; but I could have proffered all that I have written so far on the first day after I met S.Y. (as all his friends called him). Our meeting was the kind that fate arranges with a certain formulaic zeal. It took place in the last quarter of 1975 in his hometown, Kankia, 58 kilometres to Katsina and 113 to Kano, where I had my primary assignment in the National Youth service Corps as Assistant Divisional Officer (ADO) in the office of the Divisional Secretary, overlooking the Divisional Council Chambers where I first met his grandfather, who was the District Head. There was something of a quiet solidity to the oldman which differentiated him from the vibrant Disrict Head of Musawa, the chair of the Council, who happened to be the father of the radical Marxist historian, Bala Usman, with whom I had opportunities to interact a number of times during the service year. First of the interactions came when he lecturered during our NYSC orientation month at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, and later during the Sallah break when I followed the Divisional Secretary to Musawa to felicitate with the ‘constituents’. I had to engage some cultural, ‘north-south’, points with him, eating from the same bowl of tuwo shinkafa in the house of the Chairman of the Kankia Council.

Anytime I talked about wanting to meet members of S.Y’s family because I wanted to save his poems, there was this look of incomprehension on many faces. “Ask 007, he should know”, was the standard answer. Whenever I asked to know about 007, virtually everybody I met laughed in my face. It began to look truly like a James Bond mystery until, too late, I was saved from my misery by one of his inlaws who decoded the 007 tag as Shehu Umaru Yar’adua. By which time, 007 had become President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. It was only then I realised why so many acquaintances had looked at me as someone who did not need any help to arrive at his destination. It dawned on me that ‘Talk to 007’ was a way of saying ‘Go to Aso Rock if you care or dare’.

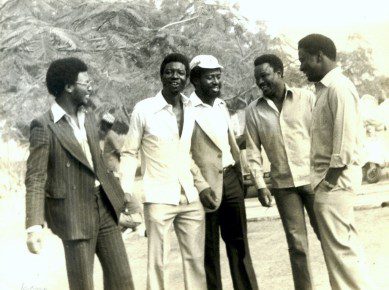

My encounters with Bala Usman were, in themselves, something of an introduction to the overarching cultural and ideological atmosphere that produced the poet I was yet to meet. We met eventually when he was visiting his hometown, Kankia, from his own primary assignment in Lagos, my famous city by the lagoon, where I had worked as petrol attendant, factory labourer and clerical officer before going to the University. It was as if we exchanged places. I left Lagos for his hometown and he had to go to Lagos. We were brought together by an admirer of his, Mallam Isa, who worked as a general factotum in the same Office with me but with whom I could not have a normal conversation because he spoke Hausa and I could not reach him in English. Mallam Isa knew me as someone always reading and writing. He had assured me he was going to bring me a friend, a man of books like me, who was serving in Lagos. One day in September, they came looking for me. They missed on a first attempt to catch me at the Health centre where I had my lodgings. I was away to Katsina, the nearest place for a cold beer in the days before I became a teetotaller.

But I met S.Y. on the streets of Kankia and found we did not need too much of an introduction. It was as if we had known each other from childhood and were merely picking up the conversation from where we left it off the day before. In a snap, I got to know about his primary school in Kankia, his secondary school in Katsina, and then Bayero University in Kano. It was in a way like meeting a younger version of his grandfather, rather taciturn and of gentle soul, as the oldman looked to me at Council meetings. His father, living in kaduna, was a civil servant who, in the future, would become one of the principal staff officers around President Shehu Shagari while I became Private Secretary to the virtual leader of Opposition.

One of the great experiences of my National Youth Service Corps year came from that visit by S.Y. to his hometown. In a fit of sassy bonhomie, he insisted he had to take me to see the kule, the women’s quarters in his grandfather’s house, supposedly out of bounds to strangers, to meet his grandmother and his many siblings – some of them students in the nearby secondary school run by a Reverend Sister. It was a treat. All the mythologies about the kule did not lead me to expect a compound very much like the one in which I grew up. But there it was. Too disappointingly similar to the compound in which I spent the first seventeen years of my life.

S.Y. had become the Director of Culture in the newly created Katsina State but had been dismissed from his job. I had heard a newsroom joke about the Governor who sacked his Director of Culture for entering a blank video tape for a national cultural competition. But I never linked it with anyone I knew. Also, I had read about the unlucky cultural officer who was summarily dismissed by Governor Madaki of Katsina State without knowing that S.Y. was the officer involved. I did not get to know the truth until his death.

His grandmother’s quarters were like those of my own grandmother who, like his own, was the oldest wife in a compound of many wives. We sat down and jisted for a while in a manner that was meant, I could see, to normalise my interaction with my new environment. Against the background of the many hair-raising stories I had heard about how different the North was from the South, he made me see it as part of the religious propaganda deployed to create a divide that distanced reality from lived experience. A divide that many played upon for purposes of power. It was a big deal for me. The reactions to me by many, young and old, in the compound, told me that mine was a visit of privilege which only an S.Y. could have pulled off. It gave me, in all our subsequent interactions, a feeling of shared conspiracy against divisive ideologues and ideologies of culture seeking to profit politically from setting Nigeria apart. It was one thing the NYSC was supposed to prepare us for. Or wasn’t it?

After that first meeting, we had graduation breaks and other breaks in the Youth Corps year to thank for meeting again in Lagos where he was serving. We exchanged, discussed and haggled over poems. After the Youth Corps year, we did not meet for a while until 1979 when, as Chief Awolowo’s private secretary, I followed my principal to Kano for the Presidential campaigns of that year. Each time we were in the city, he came to the rallies to seek me out. On one occasion I bailed out of the campaign trail to cruise around the city with him and a number of friends to see something of the city that I simply could not get enough of during my Youth service. I seized the flare of chance for the purpose of just enjoying my love of city-space. All the while we talked poetry. Lost in our own world of poesy, as I realise now on looking back, we did not mind who did not mind whoever failed to care about poetry. Whenever and wherever we met thereafter, I made sure he promised or delivered his latest poems. Over the years, I got to meet a lot of young writers who were not fastidious about how they kept their manuscripts. He was one of three – the others being Chiedu Ezeanah and late Idzia Ahmad, the chap from Gudi station, near Jos, whose death robbed Nigeria of a most promising poet.

My first thought after the initial shock was: what would happen to his poems? I immediately began the process of trying to get the final versions of the poems that he had sent to me over the intervening decade. I had sent back to him each batch of the poems that he sent to me, with suggestions for emendations. I could not be sure if the versions I had with me were the same as the ones that he eventually perfected.

Need I add: those were days before the GSM, internet and emails foreshortened all distances. Sometimes, we made no contacts for over a year, especially after he finished his Master’s degree in Kano and moved to teach at Uthman dan Fodio University in Sokoto. We never managed to see again and talk except through mutual friends, who seemed to know less and less about him and what was most clamant in my relationship with him, his poetry. He moved from Sokoto to the School of Oriental and African studies (SOAS) in London. Although I was in Oxford on a fellowship, I did not know about it until much later. We never met. Even when I moved to London on the expiration of my fellowship, we never met. This dovetailed with the era of the June 12 imbroglio when I had to return to Nigeria feeling genuinely incommoded by the three-monthly visas that kept me in research exile. It was a real emergency brewing at home that I felt should not happen behind my back. Not to forget: Those were the last days of the gap-toothed dictator General Ibrahim Babangida pitching into the more nationally divisive pursuit of peace and unity under General Sani Abacha’s dictatorship.

One day on a visit to a friend in Festac Town, after I returned to Lagos from my four year stay in the UK, I met a fair lady in a friend’s house who introduced herself as Mrs. Sada. I asked if she knew S.Y. and very chirpily she said “S.Y. is my step son”. It was like trying to knock me down with a feather. I took a second look at her and felt rather offended to see someone so young calling S.Y. her step son. Although I am myself a child of a polygamous home and ought to have understood, I yielded to the surprise. I allowed myself to be more scandalised than I should be. The good thing was that the evening brought me some news about S.Y. I noticed that this step mother was trying not to volunteer some information that literally tripped around her lips. But I let it pass.

Perhaps, if I hadn’t been too stand-offish, I may have got a hint of what I later got to know: that S.Y. had become the Director of Culture in the newly created Katsina State but had been dismissed from his job. I had heard a newsroom joke about the Governor who sacked his Director of Culture for entering a blank video tape for a national cultural competition. But I never linked it with anyone I knew. Also, I had read about the unlucky cultural officer who was summarily dismissed by Governor Madaki of Katsina State without knowing that S.Y. was the officer involved. I did not get to know the truth until his death. The sad and jolting news was delivered in the usual mode of the rumour industry in the newsroom which said his deputy in the Arts Council of Katsina State, who was out to get him out as the Director of Culture, had swapped the correct video with a blank one to get he man who just died. The man who just died turned out to be my friend.

I worried endlessly that the poems could suffer the fate of manuscripts left behind by many writers whose relations really had no interest in their literary careers. For me, the most tragic had been the case of Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, whose politics I did not like but whose literature was gem enough for any serious literary enthusiast to want to go to war for. In Tahir’s case, I missed saving his manuscripts because I failed, for some ungainly existential reason, to make the journey to Bauchi to meet him after he offered to make me the publisher of the second of a trilogy, titled The Last Imam…I still feel responsible for the loss that Nigerian literature suffered in the process.

My first thought after the initial shock was: what would happen to his poems? I immediately began the process of trying to get the final versions of the poems that he had sent to me over the intervening decade. I had sent back to him each batch of the poems that he sent to me, with suggestions for emendations. I could not be sure if the versions I had with me were the same as the ones that he eventually perfected. I had no way of knowing whether he accepted or rejected my suggestions. My search for anyone who could answer the questions kept turning out blanks.

I kept to harassing all acquaintances who could have known him. Or who could give information that could lead to someone who could have known him. Of course, many of them could not understand why I was getting all wired up and passionate about some poems that may have been published in some student journals at Bayero or Uthman dan Fodio and long forgotten with the magazines that published them. For one thing, it was a period in which I could not have indulged my love of travel by going to Katsina to seek out members of his family. Under General Sani Abacha’s dictatorship, it was not politic for the Chairman of the Editorial Board of the TheNews and Tempo magazines, so called guerrilla outfits, to get too adventurous. The times were truly precarious for the guerrilla media outfits being hunted and roughed up by the military dictatorship.

At some point, my search narrowed down to, as his friends and acquaintances assured me, meeting only one friend of his called 007 whom everybody thought I should have known if I knew S.Y. 007 and S.Y. were said to be such bosom friends, equally committed to unusual ways of doing things, equally avant garde and bohemian, if you please, in their commitment to social activism.

Although I needed to make that long overdue journey to the next-door city of my National Youth Service Corps days, prudence dictated a different kind of approach to the search for members of his family who would know how to retrieve the poems from whatever closet he had them. I worried endlessly that the poems could suffer the fate of manuscripts left behind by many writers whose relations really had no interest in their literary careers. For me, the most tragic had been the case of Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, whose politics I did not like but whose literature was gem enough for any serious literary enthusiast to want to go to war for. In Tahir’s case, I missed saving his manuscripts because I failed, for some ungainly existential reason, to make the journey to Bauchi to meet him after he offered to make me the publisher of the second of a trilogy, titled The Last Imam. Tahir was dead before I got to know that a fire gutted and took away about seven of his hand written novels. I still feel responsible for the loss that Nigerian literature suffered in the process.

I wasn’t too sure that it was a journey well worth making. Or, imagine going to Aso Rock to look for poems on a day when the President of Nigeria was in a special meeting with party stalwarts demanding this or that or bidding for Ghana Must Go Bags that the man was nonplussed about. To enter such a scene in search of poems!

I did not want such a pass to befall S.Y.’s poems. At some point, my search narrowed down to, as his friends and acquaintances assured me, meeting only one friend of his called 007 whom everybody thought I should have known if I knew S.Y. 007 and S.Y. were said to be such bosom friends, equally committed to unusual ways of doing things, equally avant garde and bohemian, if you please, in their commitment to social activism. I had not even vague recollections of S.Y. saying something about 007. I thought I met the whole circle except one, Umaru who, on the day we could have met in Kano, had gone to Katsina. Hopelessly, I reached for all the photographs taken by our resident photographer on the campaign trail in Kano. The only one in which S.Y. appeared had other faces that I could identify or get anyone I knew to identify. Besides, over the years they may have changed beyond recognition.

Anytime I talked about wanting to meet members of S.Y’s family because I wanted to save his poems, there was this look of incomprehension on many faces. “Ask 007, he should know”, was the standard answer. Whenever I asked to know about 007, virtually everybody I met laughed in my face. It began to look truly like a James Bond mystery until, too late, I was saved from my misery by one of his inlaws who decoded the 007 tag as Shehu Umaru Yaradua. By which time, 007 had become President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. It was only then I realised why so many acquaintances had looked at me as someone who did not need any help to arrive at his destination. It dawned on me that ‘Talk to 007’ was a way of saying ‘Go to Aso Rock if you care or dare’. I could imagine myself daring and being halted and asked why I needed to see the President and hearing myself say he is the only one who is supposed to know where I could find poems written by a mutual friend of ours who died a few years back. But asking the President to look for poems at a time when he was undergoing his many treatments abroad?

I wasn’t too sure that it was a journey well worth making. Or, imagine going to Aso Rock to look for poems on a day when the President of Nigeria was in a special meeting with party stalwarts demanding this or that or bidding for Ghana Must Go Bags that the man was nonplussed about. To enter such a scene in search of poems! Even if he was present-minded enough to have put his friend’s poems in fair safe keeping, they were likely to be in some obscure file, too obscure now to be remembered from among so many other papers over-swamped by political junk. I almost gave up but for a chance encounter with the novelist, Labo Yari, a Katsina indigene. His promise to locate S.Y.’s family had been the most assured I got earlier on when I began the search for the poems. I worried him incessantly in the early days of my search but had allowed a lull when it seemed it was leading nowhere.

I have chosen to deny myself the editor’s imprimatur and to present this particular poet, warts and all, as he was and as he would have preferred it. There are occasional pieces that he wrote in a joker’s mood which have their own quaint power of address beyond the more serious pieces. The impulse to publish such pieces either in a separate volume or in a special section has not appealed to me as a good way to represent a poet for whom being politically correct was not an issue to be forced. I also think that a poet should be allowed his sense of humour even in the grip of the most heated undertaking.

I brushed it all aside when in year 2000 I became self publisher of my own poetry…Then I met Labo Yari again at an Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) meeting. In Abuja. I renewed my demand for information about Sani Sada and his family. I believed he owed me a responsibility not only as an indigene of Katsina, as a fellow writer, but as a trustee of the Association of Nigerian Authors. I had not seen him at an ANA meeting since the execution, for treason, of Major General Mamman Vatsa, host of the fifth annual conference of ANA in Abuja in 1985. Although he was yet to bring me news, the fresh exchange of phone numbers was as reassuring as the first time.

In the age of the GSM that had dawned, one certainty was that even if Labo could forget, he would not be allowed to. He was not one of those who would wonder why I was. Each time I reminded him, he gave me the same old assurance: If the poems are available somewhere in Katsina, he was going to find them. One way or another, through his daughter, he would reach out to the family. In the end, he delivered. I received the poems in 2013. I was all piping hot with gratitude. Enormous gratitude, too, for members of S.Y.’s family, especially his wife and daughter who preserved the poems. Surely, S.Y. was lucky. All the poems that I remembered from our many interactions were available in the collection that Labo Yari sent to me. I wondered if there were no new things that he wrote thereafter. But I could not press an Oliver Twist syndrome too hard or too far after I got what I knew to be there.

A very rare pleasure I have felt, I mean, to be able to share S.Y.’s poetry with the whole world. A poet tends to be saved for eternity by the diligence with which the best of his and her poems are preserved. So much weeding off is often done of juvenilia and other efforts that may be considered incongruous with his general ouvre. But I have chosen to deny myself the editor’s imprimatur and to present this particular poet, warts and all, as he was and as he would have preferred it. There are occasional pieces that he wrote in a joker’s mood which have their own quaint power of address beyond the more serious pieces. The impulse to publish such pieces either in a separate volume or in a special section has not appealed to me as a good way to represent a poet for whom being politically correct was not an issue to be forced. I also think that a poet should be allowed his sense of humour even in the grip of the most heated undertaking. Hence, I have chosen to allow not so much a chronology to exist, as he wished it in his arrangement of the poems, but to let the more serious ones enter a realm of banter with the less momentous of the poems. That way, a picture of how the poet worked in moods that were not linear is turned into a part of his self-presentation.

Sani Sada happened to be a poet who, in the way he lived, bridged the gaps between the high and the low. It was a force in his life that I think deserves to be reflected in putting together his life’s work as a poet.

Or may be, I should just confess that as a poet, I have been a victim of rejection slips for poems that, when published, turned out to have a larger audience than the supposedly more correct ones. I simply would not like to see another poet suffer a fate I had escaped. Thus, I have found the pidgin poems, for instance, too powerful in their short and sharp rendering of our times, to be discarded. Nor do I want to belittle them by sectioning them. The joy of having all the poems together in a mix and knowing that they were not lost or burnt as with Tahir Ibrahim’s manuscripts dis-inclines my use of the editorial spike. I am rather indifferent to the rash aesthete who may have winnowed out many of the poems that I have accommodated without specifying their status as juvenilia.

Happily, poems that once made us laugh and others that were written to bite off the equanimity of the powers that be are still able to evoke the same force as when they were first written. This is my rationale for putting all of the poems together without attempting to be more than a proof-reader. I had all the arguments I needed to have had with the poet while he was on this side of the metaphysical divide. Unfair as it might seem to ramp them together, as it were, there is a beauty to each of the poems not to be distanced from the rest without detracting from the overall power of the whole collection. Sani Sada happened to be a poet who, in the way he lived, bridged the gaps between the high and the low. It was a force in his life that I think deserves to be reflected in putting together his life’s work as a poet.

Odia Ofeimun, a poet, political and cultural historian, writes from Lagos. He is author of the acclaimed The Poet Lied and several other collections.

This is Odia Ofeimun’s Introduction to Sani Yusuf Sada’s A Look for Sunrise, to be published by Hornbill House soon.