Global Issues

Deradicalisation In Refugee Camps and Beyond -By Alon Ben-Meir

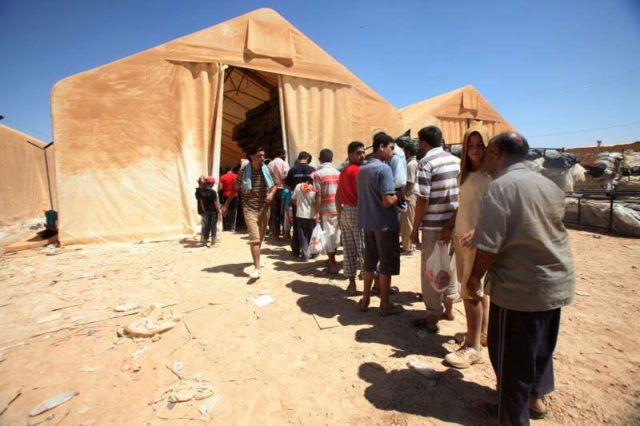

The influx of millions of Syrian refugees to Europe is more than likely to become another source of radicalisation that could increase the number of violent extremists among the refugees and lead to further acts of terror in their host countries. Depending on how long the refugees stay in camps and the way they are treated, terror attacks will either be reduced in number, frequency, and scope, or become increasingly acute once they are permanently resettled. Host countries must employ special methods to thwart any infiltration attempts by violent extremists under the guise of being refugees, and develop a countering violent extremism plan that encompasses all aspects of deradicalisation.

Host countries have little choice but to do just that because a single attack could come at the enormous cost of dozens of casualties and massive destruction, not to speak of the fear, panic, and economic dislocation that would spread throughout the community; the attacks in Paris and Brussels speak for themselves.

To achieve their objective, host countries must consider every aspect of what the refugees have experienced, both psychologically and physically, and carefully assess the short and long-term impacts that every measure will have on the mindset of the refugees so as to reduce their anxiety and enable them to embrace this new chapter in their lives.

The focus on internal security in the camps and the gathering of intelligence must receive top consideration. It should be emphasised, however, that no amount of policing or sophisticated intelligence gathering will suffice unless such activities are taken in conjunction with a host of other preventive measures.

To begin with, host countries must judiciously reflect on the trauma that nearly every refugee experiences as a result of being abruptly and often forcibly removed from their homes, leaving behind much of their possessions, family, and friends, let alone the torturous emotional ordeal of not knowing what is in store for them.

To ease this individual and group trauma, local authorities need to provide psychological counseling to the refugees, with a special focus on youth between the ages of 15 and 25, who are the most susceptible to radicalisation and may otherwise become easy prey for violent extremist groups to recruit while awaiting resettlement.

In addition to counseling, they need to be occupied with positive activities, for example, helping in the relief efforts in the camps and other administrative duties, to feel useful and relevant, which would help them regain their self-esteem.

They should also be provided new outlets for communal engagement, including professional training, sports activities, and education, not only to allay the trauma they are experiencing but also to begin the process of adjustment to a new and productive life.

Education, however, should not be limited to the youth. Teachers should also receive counter-radicalisation training and develop curricula that underscore the horrible downside of violent extremism. In addition, the families of young boys and girls should be included in the education process, as parents could hold extremist views because of their past bitter experiences.

Indeed, idleness and boredom breed contempt, resentment, and impatience. The young need to be kept informed about when their trials may come to an end, what to expect once they leave the camps, and what means they will be provided with to live with their families in dignity.

It is well-documented that the longer refugees stay in camps, the greater the risks are for radicalisation, which is further aggravated when the camps are overcrowded, unsanitary, and isolated with little or no access to the outside world.

In years past, many Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan, as well as Afghan refugees in Pakistan in the 1990s, became radicalised, and today we are witnessing the slow emergence of a similar phenomenon among Syrian refugees.

Although law enforcement is critical to prevent outbreaks of violence and criminal activity, police officers must not treat young offenders with harshness and abuse. Taking punitive action disproportionate to the severity of the crime can breed deep resentment and lead to new violent crimes and radicalisation.

To substantially reduce the level of crime, authorities should in particular conduct field studies, initiate regular outreach programmes, and engage the refugees in dialogue—listening to and acknowledging their grievances, and making every effort to address their legitimate complaints.

This is important because the refugees must believe, through day-to-day encounters, that the host country is doing all it can to support them and alleviate their pain and concerns. Outreach efforts also become an important public source to gather information and detect radical activity, terror plots, and recruitment by extremist organisations such as ISIS.

The host countries need to utilise social media to provide a counter-narrative to the voices of violent extremists who are trying to lure the youth to their ranks. This counter-narrative should not come exclusively from government officials of the host country, as many refugees view that as self-serving or potentially entrapping. It should come, in the main, from respected religious scholars, imams, and other revered individuals from within the refugee community.

Using a religious counter-narrative is critical because radical Islamist organisations resort to extreme religious precepts, however contrived, to persuade the young to join. Indeed, zealous believers do not feel the need to produce evidence to support their convictions that they are operating according to the will of God. For this reason, violent religious narratives can be effectively countered only with moderate Islamic teachings, with an emphasis on non-violent traditions and the virtue and morals of Islam.

There are two other important factors to consider in the effort to minimise radicalisation in the refugee camps. First is the proximity of the camps to the country of origin, which allows for the smuggling of weapons and drugs, and the infiltration of violent extremists into the camps, who remain inactive until such time when they are ready to commit acts of terror in the host country or bordering states.

Being that the vast majority of refugees are the victims of circumstance, they should be treated humanely and with sensitivity. Indeed, even some violent extremists can be disarmed by demonstrating compassion and understanding toward the whole refugee community, and treating them humanely and with respect.

Second, the need to provide refugees with their daily necessities may prompt tension with surrounding indigenous communities, especially if they are poor and lack access to services being provided to the refugees, such as healthcare and education. For this reason, host countries must ensure that the surrounding communities are not neglected at the expense of providing aid to the refugees.

To be sure, ignoring the surrounding communities could instigate violent conflicts between the two sides and lead to the radicalisation of young refugees in particular; these types of incidents have been cited in Jordan, Turkey, and Germany. Thus, the host country must carefully consider where to build a refugee camp and how that might impact the surrounding area.

The above measures could substantially reduce, but not eliminate, the chances of a determined violent extremist infiltrating through waves of refugees, or a refugee becoming radicalised in the camps. For this reason, host countries should continue the process of deradicalisation, mainly through integration, once the refugees are permanently resettled.

How and where to resettle refugees is a critical factor that has long-term effects on absorption and integration. It is only natural that people of the same background, who have gone through the same horrifying experiences, would gravitate to one another, but host countries should avoid concentrating thousands of refugees in one location because this prevents integration with mainstream society.

Previous waves of Muslim immigrants who settled in London, Brussels, Paris, and other European cities provide stark examples of such insular communities. Whereas families should stay together, the host countries must not create a situation where they prevent the integration process, which is central to deradicalisation.

Learning from past experiences, host countries should focus on the youth by integrating them into the local communities through activities in which their indigenous counterparts are involved.

In addition, instead of indoctrination, the youth should be provided with holistic educational experiences that draw on cognitive, affective, and performative modes of learning to help them restore their senses of self-worth.

Another important activity is to familiarise the youth in particular with the rest of the country by organising trips, joined by native peer groups, to explore their new country first-hand. This activity allows young men and women to develop a sense of belonging.

Non-governmental organisations should also play a constructive role in accelerating the process of absorption and integration by offering, for example, internships and other office work that utilises the talents these youth have while learning and adapting to a new work environment.

Host countries must ensure that prisons do not become incubators for radicalisation. Violent extremism will persist for a long time, and could dramatically increase the number of extremists within the prison population at a prohibitive cost.

To counter this, the authorities should develop a comprehensive rehabilitation programme, as reformed prisoners would best serve as role models to deradicalise other individuals, especially at-risk youth.

Finally, it is of the utmost importance to engage communities of refugees in sustainable development projects of their own choice, initially funded by the government. These types of projects allow the refugees to develop a sense of pride and achievement, provide job opportunities, and build the foundation for self-sufficiency and productivity.

Participatory projects require trainers, facilitators, and organisers, which host countries can initially appoint, but they will ultimately be run by members of the community itself, empowered by their own creative resources.

Needless to say, it is easier said than done to adopt the measures outlined above, but given that violent extremism will otherwise only fester, host countries have little choice but to invest time and resources to mitigate the plight of the refugees, starting with the refugee camps and continuing throughout their resettlement process.

Host countries cannot be long on talking and short on funding. Any government committed to deradicalising young men and women must invest, along with private donors and foundations, as much as needed to address the epidemic of violent extremism.

Moreover, whereas violent extremism can be contained or even defeated by Western countries by taking the measures briefly outlined above, the ideology of groups such as ISIS cannot be defeated any time in the foreseeable future.

We must bear in mind, however, that as we address the radicalisation phenomenon, we cannot allow ourselves to be possessed by it or permit it to undermine our social and political values, which are the strongest weapons we have to defeat violent extremism.

Alon Ben-Meir is a professor of international relations at the Centre for Global Affairs at NYU. He teaches courses on international negotiation and Middle Eastern studies, and can be reached through alon@alonben-meir.com; www.alonben-meir.com