National Issues

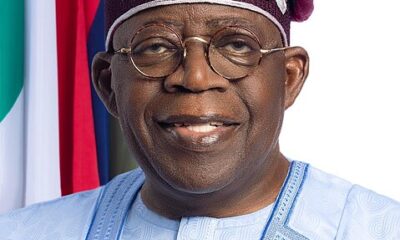

How the North Was Lost -By Chris Ngwodo

Chris Ngwodo

August 8, 1950 would have been an even more significant date if the course of Nigerian history had turned out differently. The definitive tragedy of Northern Nigeria was not, as one popular narrative holds, the assassination of the Premier Ahmadu Bello by mutineers in January 1966, heinous though that crime was. It was, instead, the deployment of chicanery and intimidation by the conservative NPC and its confederates in the British colonial administration to ensure that NEPU did not win political leadership of the Northern region. Had NEPU won, the history of the North and of Nigeria would have been dramatically different.

Exactly sixty-five years ago, eight young men of like minds met at No.4, Ibadan Street in the Sabon-Gari district of Kano city. The product of this conclave was the formal launching of the Northern Elements Progressive Union which soon became the radical nationalist bulwark of opposition to the conservative tendency represented by the Northern Peoples’ Congress. NEPU’s slogan was ‘Sawaba’ meaning “freedom” from both local despotism and external domination. NEPU’s class-based critique of the political order defined the adversaries of the people as the British colonialists and their local allies, the native authority and its vassals. Emancipation lay in throwing off the yoke of colonialism as well that of local feudal institutions.

The NEPU’s leading luminary was Mallam Aminu Kano, a scion of the Fulani aristocracy and an ardent advocate of the talakawa who made it his life’s cause to terminate the conservative power structures that he deemed responsible for their poverty. Like his fellow radicals, Aminu believed that the Northern masses had to be emancipated from the stranglehold of what he called the “Anglo-Fulani aristocracy” – the British and their local clients.

Aminu championed universal education, women’s rights and the social emancipation of a people bent double under the yoke of feudal oppression. A democratic socialist and an Islamic scholar, he synthesised leftist social analysis with Islamic liberation theology to galvanise the masses against the ruling elite who used the creed as a means of sociopolitical control. NEPU was vastly popular and it took a combination of brutal suppression by the Native Authority and electoral chicanery orchestrated by the British to ensure that the party did not win seats in the regional parliament.

August 8, 1950 would have been an even more significant date if the course of Nigerian history had turned out differently. The definitive tragedy of Northern Nigeria was not, as one popular narrative holds, the assassination of the Premier Ahmadu Bello by mutineers in January 1966, heinous though that crime was. It was, instead, the deployment of chicanery and intimidation by the conservative NPC and its confederates in the British colonial administration to ensure that NEPU did not win political leadership of the Northern region. Had NEPU won, the history of the North and of Nigeria would have been dramatically different.

NEPU’s birth in Sabon Gari, Kano, signalled its defiance of colonial divide-and-rule tactics and demonstrated its stated abhorrence of “religious discrimination”, its belief “that all persons are children of God” and its rejection of all efforts “to create a wedge between Northerners and Southerners.” This worldview informed NEPU’s friendships.

Nigerian politics is often discussed in binary terms as a struggle between a Muslim North and a Christian South. In fact, the fundamental roots of the North-South dichotomy are neither religious nor ethnic. There is a substantial population of Muslims in the South just as there is a significant number of Christians in the North. The North-South divide in contemporary Nigeria is fundamentally socio-economic and stems from a regional educational imbalance.

The emirates’ resisted Western education fearing that Christian missionaries would use it to proselytise. For their own part, the British sought to avoid facilitating the educational bequest that had created not servile Anglophiles as they had hoped, but educated worldly-wise freedom-demanding Islamists in Egypt and anti-colonial agitators in Southern Nigeria. As Shehu Shagari and Jean Boyd noted in their biography of Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio, Sir E.P. Girouard who had served in Egypt, and was Governor of Nigeria from 1907 to 1909 was anxious to avoid what he termed the mistakes that had produced “nationalistic demagogues” and discouraged the any plan to equip Northerners with the education they needed to assume full agency for their post-colonial destinies starting with the English language. This reluctance to permit education in the North endured for decades under the colonial administration.

The British authorities worked hard to prevent Southern anti-colonial enthusiasms from infiltrating the North. In Clash of Identities, Husseini Abdu details the elaborate matrix of ethno-racial segregation with which the colonialists separated Europeans, Syrians and Lebanese, the indigenous population, non-indigenous Northerners and southern Christians who they referred to as “native foreigners” and, for whom “Sabon Garis” were established as settlements. Segregation fortified the sense of otherness among various groups and thereby militated against the emergence of a common citizenship.

NEPU’s birth in Sabon Gari, Kano, signalled its defiance of colonial divide-and-rule tactics and demonstrated its stated abhorrence of “religious discrimination”, its belief “that all persons are children of God” and its rejection of all efforts “to create a wedge between Northerners and Southerners.” This worldview informed NEPU’s friendships. According to the foremost historian of the movement, Alkasum Abba, NEPU’s relationship with the Nnamdi Azikiwe-led National Council of Nigerian Citizens was so close that colonial authorities regarded it as the latter’s Northern arm.

Significantly, in 1953 and 1966, NEPU members protected southerners during episodes of anti-Igbo violence.

NEPU’s revolutionary agenda zeroed in on the fundamental problem of the North by lamenting that in 1950 its fifteen million people who had been under British rule for nearly a century had only one doctor, and not a single engineer, economist, lawyer or educationist. The progressives astutely understood that the education gap between North and South fuelled Northern paranoia about its potential post-colonial domination by the better resourced Eastern and Western regions and also fortified the status of the conservative elite in a backward milieu.

The closure of the North to education had left the region ill-equipped for the post-colonial proto-capitalist economy. In most Northern towns, Southerners (particularly, Igbos) were the agents of capitalist modernity bringing posts, telegraphs and rail lines into remote locales and also served as a nascent merchant middle class. In his book, Instability and Political Order, the scholar B.J. Dudley argued that this coincidence of ethnic and class divides set the stage for sporadic inter-ethnic clashes that began in the 1940s and reached a brutally ugly crescendo in the mid 1960s. Significantly, in 1953 and 1966, NEPU members protected southerners during episodes of anti-Igbo violence.

The 2010 Nigeria Education Data Survey showed that the chances of a typical child attending primary school in Anambra, Ekiti, Lagos or Bayelsa State are more than thrice those of such a child in Zamfara, Kebbi or Borno State. This lingering disparity has fed into other regional imbalances in economic opportunity, upward mobility, access to healthcare, teledensity and banking transactions – all of which do not favour the farthest Northern states.

The problem is not Islam but its politicisation by a parasitic elite intent on creating a supine class of destitute millions in the North with the myth of a pan-Islamic solidarity between the obscenely opulent and the criminally deprived. Socio-economic inequality exists all over Nigeria but it is especially pungent in Northern Nigeria.

In plural societies suffering adverse socio-economic conditions, issues of identity typically become more salient so it is not surprising that the North-South divide is commonly interpreted in ethno-religious terms on both sides of the Niger. In the North, it has helped nurture a Muslim Hausa-Fulani identity construct with a self-perception of being alienated and marginalised. In the South, it inspires ignorant (and Islamophobic) critiques of the North and Islam. Yet these do not explain why Southern Muslim communities are, on the average, better educated than those in the North, or why Muslims from Auchi or Ogbomosho will typically have greater chances of social mobility than their brethren in Funtua or Talata Mafara.

The problem is not Islam but its politicisation by a parasitic elite intent on creating a supine class of destitute millions in the North with the myth of a pan-Islamic solidarity between the obscenely opulent and the criminally deprived. Socio-economic inequality exists all over Nigeria but it is especially pungent in Northern Nigeria. The politicisation of religion in the North may have been inevitable given its history as a terrain, large parts of which were ruled by a caliphate for a century but socio-economic conditions have seeded a culture of violent zealotry that in the past forty years designated the southerner and the Christian as the villainous other. It has also inspired the emergence of a militant neo-Christian political identity in the Middle Belt which thrives on Islamophobic anti-Hausa-Fulani populism.

The assaults on the radical Northern progressive tradition first by the British colonialists, the conservative NPC and its successors, and finally, terminally, by military dictatorships during the 1980s, is the signal tragedy of recent Northern history. It was also during the 1980s that neoliberal economic policies wiped out the blue collar working class in places like Kano and Kaduna leaving behind a sprawling rustbelt. The South also suffered deindustrialisation but its far stronger technical and educational capacities enabled it to transit from industrial age commercial formations to information age and service sector economic constructs.

In sum, what the radical historian, Bala Usman described as “the political manipulation of religion” is why Northern Nigeria had become a theatre of sectarian strife even before Boko Haram arrived on the scene. The terrorist group is the most extreme manifestation of that tendency that rejects Western education and all other elements of Western rationality such as democracy, human rights and nation-states.

The assaults on the radical Northern progressive tradition first by the British colonialists, the conservative NPC and its successors, and finally, terminally, by military dictatorships during the 1980s, is the signal tragedy of recent Northern history. It was also during the 1980s that neoliberal economic policies wiped out the blue collar working class in places like Kano and Kaduna leaving behind a sprawling rustbelt. The South also suffered deindustrialisation but its far stronger technical and educational capacities enabled it to transit from industrial age commercial formations to information age and service sector economic constructs.

In the absence of the progressives, certain politicians have been able to use Islamo-populism, invoking Sharia less as a nod to piety than to sectarian dog-whistling for political gain. For the avoidance of doubt, Islamo-populism is about cynical electoral strategy rather than theology. In the absence of progressive critiques of an unjust social order and in a climate rife with disdain for mainstream politics and a derelict state, Jihadists have also emerged preaching violence, hate and anarchy. Herein lies the appeal of Boko Haram and similar groups.

Poverty is the experience of the majority of Nigerians but it is structurally embedded in the North because of its human capital deficit. Northern Nigeria has reared a surplus of unschooled and unskilled young adults of working age sequestered in densely populated ghettoes marinating in idleness – a virtual army of malcontents in waiting.

Poverty is the experience of the majority of Nigerians but it is structurally embedded in the North because of its human capital deficit. Northern Nigeria has reared a surplus of unschooled and unskilled young adults of working age sequestered in densely populated ghettoes marinating in idleness – a virtual army of malcontents in waiting. The theme of Northern poverty elicits little national sympathy because the region’s elite are perceived to have been politically ascendant for decades. Apart from the necessary federal reconstruction programme for the conflict-afflicted Northeast, northern state governors must simply knuckle down and deliver governance.

The recent political ascendancy of three important figures offers hope. President Muhammadu Buhari is a politician after the order of Aminu Kano. Possessed of Spartan discipline, ascetic comportment and a reputation for being incorruptible, he brings a moral authority to national leadership that will benefit both Nigeria and the North. The Emir of Kano, Muhammadu Sanusi II, a banker and a public intellectual, has brought a reformist temper to a conservative traditional institution and is an advocate of education. In Kaduna, Governor Nasir El-Rufai has unveiled a transformative agenda and has rightly prioritised education.

It is no coincidence that both Buhari and Sanusi narrowly escaped assassination by terrorists last year. This progressive trinity typifies the sort of synergy that is needed to rescue the North – a blend of federal and state political authority with the moral capital of an influential traditional institution to turn the tide in favour of progress.

Chris Ngwodo is a writer, analyst and consultant.