National Issues

On the New National Minimum Wage -By Uddin Ifeanyi

After a fashion, the ongoing discussion around a new national minimum wage for the country is turning into a metaphor of how poorly governed our space is — and how difficult it will be to fix this. When impediments to both productivity growth and the competitiveness of an economy are discussed, almost invariably, labour market reforms (making it easier for more people to be hired nearly always means making it easier to fire too) top the agenda. In this reading of the problem, collective bargaining (centralised and at the national level) has increasingly come to be identified as part of the lets to labour market flexibility in the country.

The leverage these collective negotiating structures grant labour unions means that off a good bargaining round, they may drive up the returns to their members. But higher outlays on wages, all other variables remaining the same, simply show up as increased cost to employers of labour. In the end, they make the use of capital goods more appealing, and drive up unemployment for all but the highly skilled. To this anti-competitive impulse is added the fact that set too high, minimum wages distort the resource allocation mechanism, both across and within industries.

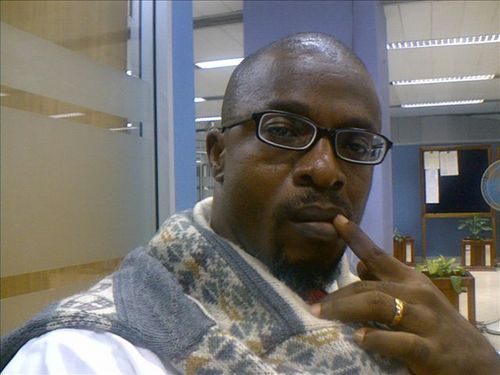

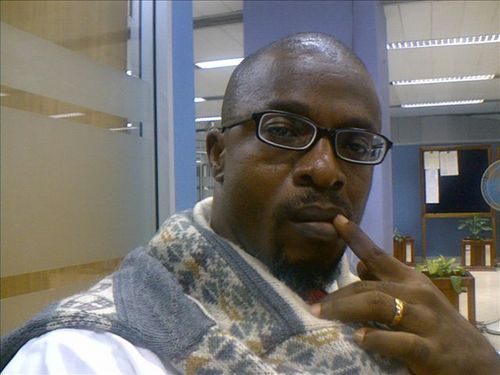

Ifeanyi Uddin

To all of these, one large advantage in our peculiar circumstance. Because the relationship between the demand for and supply of labour has broken down in our country, the higher proposed minimum wage ought not to hurt the chances of younger workers finding jobs — by pricing them out of the market, for instance. Currently, unemployment and underemployment are highest in those parts of the country where the only source of demand for new labour is from itinerant preachers. And the supply of labour is of a quality consistently unsuited to the needs of a modern economy.

Nonetheless, our practice adds the spectacle of central, state, and municipal governments headed towards a new higher wage agreement, even when most of them have had difficulties meeting the old wage bills. One of the tales told by the poor numbers out of the economy in the April to June period is how soft consumer spending has been since the economy emerged from its most recent recession. Until recently responsible for about two-thirds of domestic output, flat domestic demand has meant that the oil sector has had to bear much of the responsibility for growth since the last recession.

So, there is a strong case to be made for increasing the national minimum wage in a roundabout way — to the extent that it could lend the much needed fillip to domestic spending. However, by worsening fiscal deficits across the three tiers of government and driving our governments’ new bulimia for borrowing, the downsides to a higher public sector wage bill more than compensate for the positives. Add to this the fact that the structure of public spend (70 per cent recurrent) does not favour growth in the economy’s productivity rate. Or that by driving up labour costs ahead of countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, we simply commit not to be able to take off China the more labour-intensive jobs it is shedding as its economy shifts outward on the production possibility curve.

In considering all these, it is important that we understand that the rate of increase in the reward to labour suggested by the proposed minimum wage is clearly higher than the growth in domestic productivity. So, it is fair to assume that without improvements to the economy’s use of capital goods (better infrastructure, more efficient public sectors, a better/healthier workforce, etc.), the new wage will hurt the economy’s competitiveness. And yet, not only are we saddled with budgets in which capital expenditure accounts for less than a third of the total outlay. But at the end of each fiscal cycle, hurdles, including the economy’s increasingly limited capacity to absorb real spending, mean that we never implement half of what consensus already considered a tight-fisted outlay on capital spending.

Despite all of these, the bigger worry is that the short-run boost to domestic spending associated with salary increases of the nature being proposed may not happen. It will take a pretty large increase in workers’ wages (at the bottom of the employment log) for wage earners to feel compensated for the toll that rising prices have taken on their disposable incomes over the years. And so, not just will the spending from the new wage levels be inadequate to boost demand. In all likelihood, much of it will be spent rebuilding household balance sheets shredded by the pay-day borrowing that has sustained most public sector workers up to this point.

But how much do all this matter, given the number of voters that may be persuaded either way by the outcome of the discussions on the new national minimum wage? Ultimately, neither the answer to this latter question, nor deeper reflection on the contradictions addressed earlier will count for much. As I was recently reminded, this is “going to be a political decision. One made easier given where we are in the electoral cycle”!

Uddin Ifeanyi, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.