National Issues

Our chaotic democracy -By Abdul Mahmud

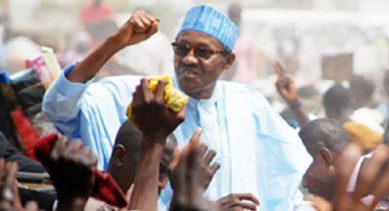

President Muhammadu Buhari

As many perceptive observers have correctly noted, chaos lies at the core of our democracy. They point to the madness, or, more profoundly, the struggle over “who gets what, when and how”, of those who squeeze the civic out of our democratic order to gain political notoriety, as evidence. The madness that characterizes fraudulent party selections and the chaos and violence that often follow our general elections make the evidence irrebuttable. Two points are implicit here: the first one concerns order as the nature of democracy.

The rooting of democracy is practically impossible in a polity reduced to chaos. The argument here is that how power is acquired is governed by rules and by the “principle of societal organization”. In effect, democracy must be rule-based in order to reduce or eliminate tension. The second one centers on representation as an essential character of democracy. For democracy to flourish the recognition of otherness and difference must exist to promote harmony and unity in the party political rank.

The evidence seems to point out the problem we are always confronted with when we elect folks who turn public offices into the wonderland of mad people, the asylum of those whom the gods have condemned to death by first making them mad with power. Do I tar everyone with the same brush? No. There are folks who unfortunately find themselves inside the insane asylum of the men and women of power and who, like Alice in Lewis Caroll’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’, despise the stereotyping because they were voted to be among mad people. I enjoin these folks to Cat’s message to Alice: “Oh, you can’t help that…I am mad. You are mad. You must be, or you wouldn’t have come here”. If the evidence truly exist, here it is: pugilists who turn the hallowed chambers of the legislature into boxing rings and their fellow colleagues into opponents or sparing partners. It doesn’t matter to them if the gavel, the symbol of legislative authority, becomes the hammer while the heads of their colleagues are the nails they hammer into nothingness.

No sane person undresses in the public and lashes at anything or everything in sight like the bull in a china shop. The emptying out of psychiatric inmates of the state asylum system into our national and states Houses of Assembly where they display animality is a yearly ritual in our part. Foucault describes this ‘emptying out’ as a voyage outside the city walls to where mad people become prisoners of their own departures. In our case, we don’t send our mad legislators outside the city walls; in fact, we send them with our votes to Abuja and the states capitals of our country to mock our collective unreason, conjure up images of our collective insanity, and create party political squabbles. No sane person undresses in the public only to put on rags of shame as our legislators have consistently done since the inception of civil democracy in 1999.

Politics makes things happen. In our case, politics makes things happen in strange ways. Consider, for example, the ceaseless Boko Haram attacks on innocent citizens in the northeast and elsewhere, conflict over land ownership and grazing rights in the north-central, the increasing theft of crude oil in the Niger-delta, and homes riven by hunger and hardship. To address these problems we need a programme of constitutional and legislative reforms and a stable legislature. How can all of this be possible when our legislators display a certain proclivity for laziness and utter disregard for the pain we endure? The problem I see here is the high purchase on power that huge pomp, emoluments, allowances, salaries and entitlement afford our political leaders that they repudiate the very essence of politics thereby making our democracy empty.

The appeal to force, might and power to resolve political conflicts, rather than seeking to mediate them through compromises and cooperation, makes our democracy chaotic. It is this appeal that births the idea that the will of the godfather is supreme or that it is the will of the godfather that constitutes the supremacy of the party, regardless of other competing wills. Not true. The idea that a political party represents the collective interests and aspirations of all members quite rightly makes the party supreme. The non-recognition of competing wills, otherness and difference, or “the difference of the other”, is most worrying. Yes, it is worrying, but I doubt if our politicians make sense of the destruction they unleash on our democracy and the chaos that threatens it. Bukola Saraki appears to make sense of this destruction when he tweeted recently, “it is time to remind ourselves of the solemn promise to deliver real change, which can’t be achieved in atmosphere distracted politics” (sic).

Will our politicians make sense of Saraki’s reminder and begin to act in a manner that makes politics less distractive or our democracy less chaotic? I doubt it. Here, the politics of chaos merely allows our politicians to negotiate new terms and framework favorable to their pursuits and engagements and to enjoy new privileges and entitlements. Saraki’s reminder, though correct, is a curious one, which makes sense only if our politicians accept that representation is not about sharing “two hundred positions” as a certain Abdulmumin Jibrin gleefully let out as the odious carrots of reward at the disposal of his House principal, Yakubu Dogara.

Can our politicians redeem themselves? Can we fix our politics? Can we bring order back to our democracy? Yes, but it appears already late. The bull is no longer in a china shop; it is rampaging through our quarters of governance. Consider this: two acting Directors-General were announced at the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) within three days. That too is chaos!