National Issues

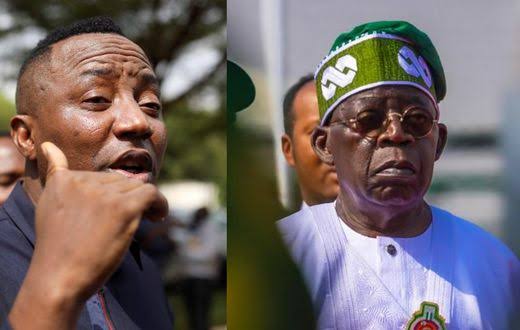

A Global Call to Vigilance: Sowore’s Ordeal, Police Overreach, and the President’s Chance to Safeguard a Fragile Democracy -By John Egbeazien Oshodi

In the days before his detention, Sowore stood alongside retired and serving police officers voicing grievances so ordinary they are rarely news—arrears unpaid, wages too thin to live on, and conditions that grind people down. For any institution, the public sight of its own members protesting is a sharp embarrassment. It does not merely speak of “discontent”; it points to promises unkept, to decay inside the walls, and to the possibility that leadership has stopped listening. When an outsider with a wide audience joins such a protest, that embarrassment deepens into a challenge.

This is an appeal framed in the language of restraint rather than fury. It asks only for light where there is shadow, for the paperwork that anchors trust, and for the medical assurance that turns down heat instead of feeding it. Omoyele Sowore is not just another name in a local dispute; he is a lawful permanent resident of the United States, with a wife and children in America. His case crosses borders not through political slogans but through the plain duties any state recognizes: consular notification, humane custody, timely access to counsel, and transparent court oversight. If these basic responsibilities are met quickly and openly, tensions ease. If they are not, what could be resolved quietly hardens into an unnecessary reputational wound.

The Invitation Turned Trap

The cruelty lies in the sequence. Omoyele Sowore did not arrive at police headquarters as a fugitive or a man in hiding; he came because the IGP’s Monitoring Unit invited him—stepping forward in the belief that process would be honored. What followed was not the civility owed to a citizen who answered a state’s call, but its inversion: an injured arm, gas in his cell, a forced transfer to an undisclosed location, and silence about his condition. To summon a man in the name of law and then harm him is not just a breach of procedure; it is a signal that erodes the trust on which lawful summons depend and stains the idea that the law protects those it commands.

What Lit the Fuse

In the days before his detention, Sowore stood alongside retired and serving police officers voicing grievances so ordinary they are rarely news—arrears unpaid, wages too thin to live on, and conditions that grind people down. For any institution, the public sight of its own members protesting is a sharp embarrassment. It does not merely speak of “discontent”; it points to promises unkept, to decay inside the walls, and to the possibility that leadership has stopped listening. When an outsider with a wide audience joins such a protest, that embarrassment deepens into a challenge.

What made this moment even more combustible is that Sowore has been an open and persistent critic of the current Inspector-General of Police, Kayode Egbetokun, questioning the legality of his appointment and the extension of his tenure. He has done so publicly and repeatedly, referring to him as an “illegal IGP.” In the hierarchies of uniformed command, such words are rarely taken as policy debate; they are felt as direct affronts. And when pride and authority feel exposed, the instinct often shifts from defending policy to defending position. In that space, retaliation can begin to look like enforcement, and enforcement like punishment.

But in a democracy, personal offense is not resolved with a cell and a baton. If a leader believes he has been wronged, the remedy is not detention and abuse — it is the civil court, where evidence is weighed and words are tested against law, not against the walls of a detention room.

A Question of Authority

Sowore has long raised questions about police leadership, including public challenges to the legality of the current tenure at the very top. Even if framed as constitutional critique, repeated in the open and carried by a loud megaphone, such questioning lands as a personal affront inside hierarchical institutions. Rank-and-file may shrug; command often cannot. In the psychology of power, the difference between policy criticism and status threat is not academic. Once an argument is heard as an assault on legitimacy, bureaucracies stop persuading and start protecting themselves.

The Turn Toward Punitive Logic

What followed, according to multiple accounts, looked less like an effort to answer the officers’ grievances and more like a re-centering of force on the loudest critic. Allegations surfaced—“forgery,” “incitement”—that read, to many observers, as catch-all charges used to create custody rather than test evidence. This is the juncture where rule-of-law hygiene matters most. The demand is not for favors but for sequence: show the warrant, show the order, show the file, show the time stamps. When the paperwork is clean and visible, the temperature drops. When it is hidden or shifting, people assume vengeance where the law should be.

Pain as a Message

Reports from counsel describe a violent transfer, a severely injured arm, and the use of a noxious agent inside a cell. If accurate, those details signal something beyond restraint—they suggest pain was part of the communication. States sometimes forget that pain talks. It says, “we can.” It also says, “we will.” In custodial settings, the ethical remedy is straightforward and non-political: immediate independent medical evaluation, documentation of injuries with photographs and measurements, a written treatment plan, and copies furnished to counsel and family. These are not concessions; they are the baseline duties set out by ordinary law and the Mandela Rules. Meeting them promptly does not weaken institutions; it protects them.

Courts in the Crosswind

There is also public speculation about efforts to secure a friendly judicial order—what Nigerians wearily call “shopping.” Whether true or not, the perception alone is damaging. Courts gain their authority from distance: distance from heat, from personalities, from the night’s emotions. When litigants appear to pick the room before they make the argument, the robe is dragged into the street.

For God’s sake, not an Abuja judge—not this time. The Chief Justice of Nigeria, Kudirat Kekere-Ekun, should make it clear that in this case the nation’s judiciary will not be used as a tool to silence a critic. She can, and should, affirm that Omoyele Sowore has the right to speak without fear of judicial convenience being turned into a muzzle.

Here, the antidote is procedural sunlight—random assignment, open hearings, reasons on the record, and timelines that cannot be bent by phone calls. No speeches required; just process that can be read and re-read.

The Presidency’s Long Silence

The highest office has, so far, spoken softly or not at all. Silence can be strategic; it can also be misread. In moments like this, a limited, carefully worded statement does a quiet kind of repair: an affirmation of the right to protest within the law; an instruction that custodial standards—including medical care and access to counsel—be audited and certified; a reminder that the courts, not emotions, will decide. None of this requires choosing sides. It simply declares that the constitution still has a voice.

Quietly Turning the World’s Gaze

In moments like this, the health of any democracy is measured not by the comfort of its leaders, but by the space it allows for dissent—especially dissent that unsettles the powerful. Omoyele Sowore has often spoken against Nigeria’s highest offices: the presidency, the police leadership, the judiciary. In some systems, such voices are celebrated as evidence of resilience. In others, they are treated as irritants to be removed.

The current silence from within Nigeria’s institutions is why the eyes of friends abroad matter. Nations that speak often of democratic partnership—countries like the United States, Germany, Canada, Britain, and France—do not need to be told what is at stake here. Their own histories have taught them that the suppression of one voice can, over time, shrink the rights of many.

For decades, repressive states have hidden behind the tired phrase “don’t interfere in our internal affairs”—as if sovereignty were a shield for abuse. But in a world joined by treaties, trade, and shared values, that shield no longer holds when rights are trampled in the open. Human rights are not an internal matter; they are the common currency of the global order.

This is not about instructing Nigeria; it is about affirming the values these nations already share with it—values written into charters, treaties, and diplomatic pledges. By quietly encouraging the full observance of due process, humane custody, and judicial independence, they help ensure that this moment does not harden into a precedent where criticism of leadership becomes a punishable act.

In doing so, they would not be taking sides in Nigeria’s political disputes. They would be standing on the side of the constitutional promises Nigeria has already made to its own people—and the world.

The Trans-Atlantic Thread

Because Sowore is a U.S. permanent resident with immediate family who are American citizens, the case implicates routine (not dramatic) cross-border steps: confirmation that consular channels are open; verification of contact with family; facilitation of independent medical review; and clarity about charge status, venue, and schedule. These are the kinds of bureaucratic acts that prevent congressional queries, human-rights letters, and newspaper editorials from hardening into diplomatic problems. They also reassure a family trying to sleep in another time zone.

What Responsible Actors Can Do—Quietly, Now

Prosecutors can either file a complete, coherent charge within a fixed timetable or publicly acknowledge the need to release while investigations continue. Police leadership can certify, in writing, that the detainee has been seen by an independent doctor, that analgesia and immobilization have been provided if required, and that counsel met with the client without interference. Courts can require production of medical notes and the custody log at first appearance. The national human rights body can be invited—invited, not cornered—to observe. International partners can request updates through ordinary channels rather than press conferences. None of this is theatrical. All of it is stabilizing.

Why This Moment Matters Beyond One Man

Every democracy periodically faces a small, combustible moment when pride, pain, and process collide. The quickest path out is not moral victory; it is administrative clarity. If due process is seen to work when tempers are hottest, institutions grow taller. If not, citizens learn a different lesson—that power answers embarrassment with injury, and that courts arrive last. That lesson is expensive; it is paid in cynicism, in silence, and eventually in exits.

A Measured Call

This is not a complicated demand; it is the bare minimum a lawful state owes to itself: produce the orders, treat the wounds, name the court, allow the lawyer, inform the family, file the charge—or let him walk free. Anything less feeds the rumor that the police fear the light, that the courts can be bent, and that the presidency will watch while its own democracy is diminished. And it leaves a family—far from home—gripping the kind of fear no government should willingly create.

The writer has no personal relationship with any party in this matter and no stake in Nigeria’s domestic rivalries. The concern expressed here is only for the health of democratic practice, the protection of due process, and the quiet growth of institutions that are stronger when they are transparent.

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, educator, and author specializing in forensic, legal, clinical, and cross-cultural psychology, with expertise in police and prison science, juvenile justice, and family dependency systems. Born in Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and the son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, his early immersion in law enforcement laid the foundation for a lifelong commitment to justice, institutional transformation, and psychological empowerment.

In 2011, he introduced state-of-the-art forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology. Over the decades, he has taught at Florida Memorial University, Florida International University, Broward College (as Assistant Professor and Interim Associate Dean), Nova Southeastern University, and Lynn University. He currently teaches at Walden University and holds virtual academic roles with Weldios University and ISCOM University.

In the U.S., Prof. Oshodi serves as a government consultant in forensic-clinical psychology and leads professional and research initiatives through the Oshodi Foundation, the Center for Psychological and Forensic Services. He is the originator of Psychoafricalysis, a culturally anchored psychological model that integrates African sociocultural realities, historical memory, and symbolic-spiritual consciousness—offering a transformative alternative to dominant Western psychological paradigms.

A proud Black Republican, Professor Oshodi is a strong advocate for ethical leadership, institutional accountability, and renewed bonds between Africa and its global diaspora—working across borders to inspire psychological resilience, systemic reform, and forward-looking public dialogue.