National Issues

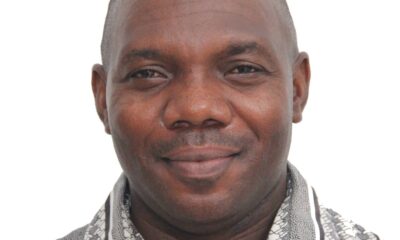

An Appraisal Of The Gombe State Sharia Court Of Appeal Rules, 2019 -By Ibrahim M. Attahir, Esq.

This development in Sharia Courts may not be unconnected with the provisions of Section 256 (1) (c) of the Evidence Act, 2011 which is to the effect that the Evidence Act is not applicable in Sharia Courts, Customary Courts, etc. My attention has also been drawn to a decision of the High Court of Borno State sitting on appeal in the case of FALMATA MOHAMMED KAWAR MAILA & ANOR. Vs. MALLAM BUKAR BINTUMI.

INTRODUCTION

In the Name of Allah the Compassionate the Merciful.

I recently read a news report in The Nigerian Lawyer blog that Rwanda scrapped 1000 colonial era laws. Here in Nigeria, it takes us half a century to amend a provision in one section of such colonial or post-colonial era laws and it becomes a subject of celebration.

In this our sad situation, the step taken by the Hon. Grand Kadi of Gombe State to come up with the Gombe State Sharia Court of Appeal Rules, 2019 (GM Rules) is commendable and worthy of emulation. His giant stride prompted me to undertake this appraisal with the aim of identifying, analyzing and commending the innovations. I will also point out some of the provisions of the Rules that need to be reconsidered whenever there will be an amendment of the Rules.

I hope it will not take this long again before we see changes in the new Rules. The digital technology comes with changes in all aspects of our life in a very speedy manner. It is referred to in ICT parlance as an age of disruptive technologies. If our laws remain static, they cannot govern our activities effectively.

HISTORY

The history of the Sharia Court of Appeal Rules is not long. Before the colonial era the courts used the Islamic books as their reference materials. Most of the classical books on Islamic jurisprudence do not separate between the substantive law, evidence and procedure. The three are discussed together while discussing substantive laws on each offence. Books of Islamic Law that appear to deal with evidence and procedure such as Ihkaam Al-Ahkaam and Tabsiratul Hukkaam , still combine the three. It was with the coming of the colonial era when the Muslim Court of Appeal, (the precursor of the Sharia Court of Appeal) was established that the Rules of Procedure were separately made for the Court.

The Sharia Court of Appeal Rules of Northern Nigeria (NN Rules) started at independence in 1960. When the regional arrangement was abolished in 1966, the six states created out of the defunct Northern Region in 1967 continued with the NN Rules. The North East Sharia Court of Appeal did not have its own Rules. Similarly, when the defunct North East was split into Bauchi, Borno and Gongola States in 1976, there was no new Sharia Court of Appeal Rules in Bauchi State. There was only the Sharia Court of Appeal Law.

When the former Bauchi State was split into the present Bauchi and Gombe States in 1996, the latter did not come up with Sharia Court of Appeal Rules.

Therefore, the NN Rules was used for 59 years. A breakdown of these years will show that 7 years were spent under Northern Region/Group of Provinces, 9 years under North Eastern State, 20 years under the former Bauchi State and 23 years under present Bauchi and Gombe States. One can excuse the years spent under Northern Region/Group of Provinces and North Eastern State because the Region/State was still at its formative stage. However, the former Bauchi State used the NN Rules from 1976 to 1996 (20 years) and after the creation of Gombe State from 1996 to 2019 (23 years) making a total of 43 years.

Gombe State used the NN Rules for 23 years. I am not aware of a single amendment in the two states before 2019. Therefore, even if what the present Hon. Grand Kadi did is just removing the name of Northern Nigeria and putting that of Gombe State, he must be commended for having the will to do just that. He has departed from the bad practice of retaining and having the so-called received English Law governing our affairs when the English people discarded same for close to a century.

STYLE AND ARRANGEMENT

The GM Rules follows virtually the same style and arrangement of Orders and Rules with that of the NN Rules. The NN Rules started with “Title and interpretation” under its Order I while the GM Rules started with “Citation and interpretation” under Order 1. The noticeable difference is in use of citation instead of title and use of Arabic Numerals instead of Roman Numerals in the arrangement of the Orders. However, the GM Rules is longer than the NN Rules with the former having 24 Orders while the latter had only 14 Orders. This difference is understandably so because of the innovations brought about by the GM Rules. Both Rules have two Schedules. But the GM Rules has more forms in the First Schedule due to the many innovations introduced in it.

INNOVATION AND REPLICATION

When a new law is made after one that existed for more than half a century, new changes and departure from the old practices should be expected. Therefore, the GM Rules introduced many positive changes. I will attempt to identify and analyze the provisions in their serial arrangement as follows:

1. Order 1 of the GM Rules is on citation and interpretation. However, while the NN Rules interpreted only “the court” and “the court below”, the GM Rules interpreted a total of 11 words/phrases. The increase in the number of the interpreted items is due to many innovations in the GM Rules. Expression in the new provisions such as: “electronic device”, “endowment”, “holiday” have been interpreted.

2. Order 2 is on Sessions of the Court. The noticeable change is the reduction in the length of time of notice of sessions from three weeks to two weeks.

3. Order 3 relates to procedure on appeal. The NN Rules, Order III Rule 1 had only 3 Sub-Rules under it. But in the GM Rules Order 3 Rule 1 has Sub- Rules 1 – 5. The first new provision is under Order 3, Rule 3 (3) which specifically mentioned transmission of exhibits. There are other innovations in sub-rule 4 and 5 on failure to transmit record. Order 3 Rule 2 introduced 14 days as the time limit for appeal against interlocutory decisions which was not provided for in the NN Rules.

Order 3 Rule 4 (1) of the GM Rules is more or less a paraphrasing of Order IV of the NN Rules except that the former has specifically introduced personal service of notice of appeal. Order 3 Rule 4 (2) is a rider to the preceding sub-rule 4 (1). Order 3 Rule 4 (3) makes specific provision on substituted service and its mode. Unfortunately, no mention is made of pasting on the court notice board. Order 3 Rules 5 on address for service contains an innovation on giving active mobile telephone number, email and other electronic devices. However, there is no provision for filing an affidavit or attestation by the bailiff that effected service by substituted means and service through electronic means.

The provision of Order 3 Rule 6 of GM Rules is a reproduction of Order III Rule 5 of the NN Rules. The power given to a single Kadi to make an order for deposit of cost appears to be contrary to the constitutional provision on composition of the Court under Section 278 of the Constitution and Section 4 (3) of the Sharia Court of Appeal Law.

Order 3 Rule 8 (3) is another innovation that provides for filing of briefs. However, the use of “will” instead of “shall” and “is to file” instead of “shall file” do not appear to make the filing of briefs mandatory. The 21 days for appellant and 14 days for respondent appear to be tight especially where the counsel involved is very busy. It should be borne in mind that with the Federal High Court, NICN, State High Court and Sharia Court of Appeal around, there may be many addresses or briefs that counsel or office may file within a short time. Moreover, the Court of Appeal periodically sits in Gombe. The appellant should be given 30 days and respondent 21 days to file their respective briefs. The Sharia Court of Appeal is not like an Election Petition Tribunal that has time limit for hearing and determination of cases. I am not unmindful of the issue of the quarterly return of cases. However, with the introduction of written brief, many appeals can be heard in one sitting and reserved for judgment. The Court will not have problem with the quarterly returns.

Order 3 Rule 8 (4) and (5) are very good innovations that relate to departure from the Rules with regards to filing of briefs in exceptional circumstances such as where there is need for accelerated hearing or where one or both parties are not represented by counsel or where one counsel files brief and the other wants to concede to the appeal orally.

Order 3 Rule 10 is another innovation giving an automatic stay of execution for three months in matrimonial cases. This provision will safeguard the confusion that is caused where the divorced wife quickly contracts another marriage and becomes pregnant while there is a pending appeal on her previous marriage thereby foisting a condition of helplessness in the whole process. However, even without the automatic stay, a divorced wife must undergo waiting period which in most cases run up to three months before contracting another marriage. The period of automatic stay should be longer. I would have also loved to see a provision here that in monetary judgments an appellant seeking for stay of execution shall deposit the judgment sum to be kept in an interest-free bank account pending the determination of the appeal.

4. Order 4 is entirely a new provision. Order 4 Rule 1 limiting the number of amendments by a party to two apparently aims at speedy hearing of appeal, which is good. But such a tight provision may defeat the aim of justice in some circumstances. For example, where the amendment becomes necessary not because of anything on the part of the party seeking for it but because the other party applied and got leave to join other parties or amend his process which will necessitate consequential amendment after exhausting the two he is entitled to. This provision needs to be reconsidered. Speed should not be the ultimate aim of justice delivery. Administration of justice is not a mechanical process. A court of law may make return of one hundred cases in a month and still be rated low if its decisions are always set aside on appeal.

5. The whole of Order 5 is also a new provision specifically dealing with extension or enlargement of time for doing anything.

6. Order 6 is on appeals out of time. Order 6 Rule 3 (1) (c) requires attaching a copy of the ruling or judgment appealed against to the motion for extension of time. That was what we were doing even when there was no such provision just out of desire for good practice. Legal Practitioners in this jurisdiction have been putting GSM numbers and e-mail addresses on processes filed in court even when there were no such requirements. Order 6 Rule 5 is also a new provision on computation of time similar to that of the Interpretation Act .

7. Order 7 on execution and enforcement of judgments is substantially a replication of Order V of the NN Rules.

8. Order 8 is on power of the Court to exclude members of the public. It is a replication of Order VI of the NN Rules.

9. The whole of Order 9 is a new provision dealing with effect of non-compliance with any provision of the Rules. Most Rules of Court have similar provisions that aim at saving court processes that have defect affecting time, place, manner, form, etc. Such non-compliances are considered as mere irregularities which can be cured or regularized. I think the statement that “the failure shall not be treated as an irregularity” is an error. The correct statement should be “the failure shall be treated as an irregularity”. That is why the concluding part of that Rule reads: “but the Court may give directions as it thinks fit to regularize the irregularity”. If it were not an irregularity, there would not have been the need to regularize it.

10. Order 10 Rule 1(5) (c) is also a new provision taking care of a situation where the Court sou motu strikes out an appeal.

11. Order 11 is on witnesses. It is a replication of Order VIII of the NN Rules which is also on witnesses except that there are few changes in semantics and style.

12. Order 12 is on orders. It is a replication of Order IX of the NN Rules. However, Order 12 Rule 2 clarifies that it is not always that judgment will be delivered in open court. There is also an addition of Rules 5 and 6 that relate to the power to order for arrest of any person who disobeys orders of the Court.

13. Order 13 is on costs. It is a replication of Order X of the NN Rules but in a different style.

14. Order 14 is on bailiffs, messengers and interpreters. It is substantially the same with Order XI of the NN Rules on the same issue. However, in the heading and the content of the latter, there is no mention of bailiffs.

The Court needs to address the issue of interpreters/translators. Trained lawyers that know judicial language should be employed to handle the issue bearing in mind that when a cases go to the Court of Appeal, some members of the panel there may have to rely on whatever shabby translation is made.

15. Order 15 is on court forms. It is also a replication of Order XII of the NN Rules. However, in the GM Rules the forms are found in the First Schedule and the Second Schedule. This is because the innovations brought by the GM Rules necessitated provision of many new forms. It is also noticeable that Order 15 Rule 2 has no sub-rules. What is separated in Order XII Rule 2 (1) and (2) in NN Rules is collapsed into Order 15 Rule 2 in GM Rules.

16. Order 16 is on fees. One of the funny things about the NN Rules is that it was in operation in this State up to 9th October, 2019 but the Scale of Fees in the Second Schedule Part II was in Pounds, Shillings and Pennies! Nobody saw the reason to change the Scale to Naira and Kobo which became legal tender since 1973. That is a period of 46 years. It means we lived in the past for that long time before the new Rules came into force.

This Order brought many changes apart from changing the name of the currency in which court fees shall be paid. The important changes include payment through bank, production of bank tellers to the court, reduction or remission of fees, exemption of official processes from payment of fees. However, the power given to a single Kadi under Order 16 Rule 4 (1) is apparently in conflict with constitutional provisions as earlier stated on similar provisions.

17. Order 17 is on records. It is a replication of Order XIV of the NN Rules. There is only a slight change in arrangement of the Rules under it and change of nomenclature from Registrar to Chief Registrar.

Order XIV is the last order of the NN Rules.

Therefore, Order 17 of the GM Rules is the last that has origin from NN Rules. Orders 18, 19, 20 21, 22, 23 and 24 of the GM Rules are entirely new provisions on sittings of Court and vacation, Al-Sulh, legal year and valedictory sessions, probate and general administration of estate, supervisory powers of the court, motions and other applications and revocation respectively.

18. Order 18 is on sittings of the Court and vacation. Introducing vacation makes it necessary to provide for a vacation panel to take care of urgent situations. The provision of Order 18 Rule 4 is to the effect that vacation period of the Court shall not be reckoned in computation of time. This provision can be a double-edged sword. We hope to see the advantages and disadvantages of the provision when it is operated for some time. The introduction of Ramadan Vacation is of benefit to the Hon. Kadis, litigants and counsel that may be preoccupied with religious rites, travels and other preparations for Sallah.

19. Order 19 on Al-Sulh (Arbitration) is a welcome development. Recourse to ADR is the modern trend in judicial circles. The concept of ADR is recognized and encouraged under Sharia especially in complicated cases as stated in Ihkaamul Ahkaam . There are many textual provisions supporting it. Both trial and appellate courts in Nigeria have a window for ADR. Mechanism of ADR is good especially in matrimonial, inheritance and other family related matters, which are within the jurisdiction of the Court.

However, the involvement of a panel of Kadis in the arbitration process may come with its challenges. The Hon. Kadis should not be involved in the arbitration. The Sulh mechanism should just have a desk officer or coordinator and supporting staff that should be trained in Sharia and modern ADR procedures. I am not comfortable with the provision of Order 19 Rule 3 that the Sulh Panel shall report its findings to the Hon. Grand Kadi for adoption. Is it the Hon. Grand Kadi that will adopt it, or he is to assign another panel for the adoption? The arrangement appears to be problematic/ awkward.

All the courts I know that have mechanism for ADR do not involve judicial officers in handling the ADR. A desk officer or coordinator or director or administrator is, mostly, put as head of the mechanism. The neighboring Borno State High Court has an ADR mechanism called “Borno Amicable Settlement Corridor” (BASC) under an Administrator/Coordinator. The BASC has its own Practice Directions . One of the Doors under the Corridor is that for Sulhu in cases of Islamic Law.

My findings indicate that the Sulhu Door has been operating successfully. Other Doors under the Corridor include Early Neutral Evaluation, Mediation and Arbitration. Article 6.1 of the Practice Directions provides that: “If a settlement of the dispute is reached, it shall be reduced to writing and signed by the parties and witnessed by their counsel. Where the matter is before a court, the parties or counsel shall within 10 (ten) days of the agreement, have the agreement filed with the Court and take appropriate steps to dispose of the action”.

The Borno State Sharia Court of Appeal Rules, 2018 also has provision for Sulhu under Order 8. Order 8 Rule 1 provides for referral of the matter for Sulhu in appropriate circumstances. Order 8 Rule 2 provides that when the Court receives report from the Arbitrator, it may confirm the award or set it aside and fix a date for hearing of the appeal. There is a similar provision in the Bauchi State Sharia Court of Appeal (Amendment) Rules, 2019 .

20. Order 20 is on legal year and valedictory session. Apart from the ceremonial value, I do not know of any practical value of the legal year ceremony even in the High Court from where it is borrowed. Valedictory session is usually held either for a retiring or deceased judicial officer. I am not aware of any provision of Sharia that is against saying goodbye to a retiring colleague. However, Sharia is against turning death of any person to a ceremony. Therefore, I hope the Court will not extend valedictory sessions to cover death of Kadis. Happily, the wording of Order 20 Rule 1 (3) is not categorical on the type of valedictory sessions.

21. Order 21 is on Probate and general administration of estate. Fortunately or unfortunately, Order 1 Rule 2 that deals with interpretation has not defined what is meant by “Probate”. That means we are left to resort to dictionary and plain meaning of the word. According to an online dictionary/encyclopedia, “probate” means “a legal process in which a will is reviewed to determine whether it is valid and authentic. Probate also refers to the general administering of estate of a deceased person’s will or the estate of a person without will”. I think both meanings are applicable here because both concepts are mentioned under Order 21, Rule 2 (1).

I am unable to understand many things about the provisions on probate. On the face of the provisions, it appears that the intention is to address the problems associated with estate of deceased persons as stated under Order 21 Rule 1 (b). However, we are aware that there is a probate registry in the High Court. I do not know the line of demarcation between probate registries of the two courts because there is none in the Rules. If there is no proper demarcation, confusion and conflict may arise. May be after operating the new Rules for some time, the propriety or otherwise of some of the provisions will be appreciated especially if tested on appeal. For now, creation of probate registry by the Sharia Courts of Appeal appears to be the trend. See Order 19 of the Bauchi State Shari Court of Appeal (Amendment) Rules, 2019 .

In my humble opinion, there will be need for a legislative intervention by amending the Sharia Court of Appeal Law, the High Court Law and the Area Courts Law to provide for a clear demarcation so as to avoid possible conflicts. If there is no legislative intervention, we have to wait until judicial interpretation is sought before the courts and the issue is finally settled. The provisions on probate under the GM Rules are not elaborate enough to guide the operation of the probate registry.

Order 21 Rule 2 (1) (a) appears to give the Probate Registry too wide powers beyond the mandate of a probate registry. It says : “The Probate Registry has the power to take custody of Gifts, Endowment, Wills, Inheritance allotment of a minor and insane person and other related matters in the following circumstances – (a) custody of Wills Gifts, Endowment and other instruments by persons, which shall be under seal of both the person requiring custody of same and the Court.” Bauchi State Shari Court of Appeal (Amendment) Rules, 2019 also has similar provisions under probate registry.

I know that in classical and even some modern works on Islamic jurisprudence Hisbah and Waqf (endowment) are mentioned as part of the mandate of the judiciary . However, in the reality of contemporary governance, endowment is within the realm of executive arm/branch of government. Many Islamic countries have Ministries of Endowments and Islamic Affairs. That shows that they do not consider endowment as part of judicial mandate. The agencies or commissions for endowment established by some states in Nigeria are under the executive arm of their governments. Jurisdiction of the Sharia Court of Appeal over Wakf under Section 277 (2) (c) of the Constitution is in judicial not administrative capacity. Extending such jurisdiction to cover administration/management of Wakf is a bit confusing.

Having endowments managed under a court may also create a conflict when eventually disputes arise from the endowments. The court may be joined as a party. It will be awkward. Moreover, the Sharia Court of Appeal is an appellate court that does not have jurisdiction at first instance. Therefore, if any dispute arises, the matter will have to go to an Area Court which is lower in rank. The case may eventually rise on appeal to the Sharia Court of Appeal and it may look like the Court is sitting as judge in its own case.

22. Order 22 is on supervisory powers of the Court.

This is a welcome development. However, the provisions are too scanty. The supervisory powers of the Court as contemplated under Section 277 (1) and (2) of the Constitution should be beyond review and stay of proceedings especially that the nature of the review has not been limited. There is need for elaborate provisions on the judicial review which should include something akin to certiorari, mandamus, prohibition, etc.

23. Order 23 is on motions and applications. There are many innovations under this Order. The most prominent one is associated with written addresses and time for filing same. However, there is no provision in the circumstances where the parties that file and exchange addresses do not appear. There is a similar lacuna in Order 3 Rule 8 (3) on filing of briefs. The practice in all other courts is that where a brief or written address is filed, the mere absence of the counsel or party will not affect the processes. It will be deemed adopted. Without such a clear provision, the Court may be tempted to strike out the process.

There is an emerging disagreement on use of affidavits in Sharia Courts, the GM Rules provides for use of affidavits. However, the Borno State Sharia Court of Appeal Rules, 2018 has discarded use of affidavits and provides for motion to be supported by statement of facts and opposed by counter-statement of facts. Similarly, the Bauchi State Sharia (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2001 specifically provide that: “A motion need not be supported by affidavit but shall be supported by sufficient argument, explanation or evidence in favour of the grant thereof”. On the other hand, the Bauchi State Sharia Court of Appeal (Amendment) Rules, 2019 provides for use affidavit.

This development in Sharia Courts may not be unconnected with the provisions of Section 256 (1) (c) of the Evidence Act, 2011 which is to the effect that the Evidence Act is not applicable in Sharia Courts, Customary Courts, etc. My attention has also been drawn to a decision of the High Court of Borno State sitting on appeal in the case of FALMATA MOHAMMED KAWAR MAILA & ANOR. Vs. MALLAM BUKAR BINTUMI. The Court held that: “In deed, in all humility, we are of the view that the emerging practice of filing motions supported by affidavits before Sharia Courts is erroneous. Affidavit as a means of proving an asserted fact is alien to Sharia. Sharia Courts should discountenance it and remain true to their calling. Facts alleged before Sharia Courts shall be established in accordance with the applicable law in that court. Importing such alien law practices, as proof by affidavit is, serves neither the Sharia nor the society…” The case of ABEBI VS. AMBALI ALAO is another example. The Kwara State Sharia Court of Appeal held that affidavit evidence is an assertion which is subject of proof once challenged.

It is not in doubt that affidavit is alien to Sharia. According to Black’s Law Dictionary , an affidavit is: “A voluntary declaration of facts written down and sworn to by the declarant before an officer authorized to administer oaths, such as a notary public”. Going by this definition, there is no much difference between an affidavit and statement of facts. The Difference may be in terms of who is the declarant, the person authorized to administer oath, the mode of taking the oath, etc. There is also the argument that Sharia has its own means of proof, which do not include affidavit. However, it is important to note that Sharia has its own dynamism and does not reject everything merely because it is alien. There are many things of colonial origin in the Nigerian Legal System. My humble opinion is that when the GM Rules and Rules of other sister states will be reviewed in future, this issue of propriety or otherwise of use of affidavit in Sharia Courts should be critically reconsidered.

Contemporary writers on practice and procedure under Sharia accept the use of evidence obtained through modern technologies such as fingerprint, police dogs, exhumation, CCTV footages, etc though they may be considered alien to Sharia. The jurists only insist that some conditions must be met and the court must always warn itself before relying upon them because of the possibility of tampering with such technologies. Notary Public may also be considered as alien to Sharia. However, Article 93, 94, 95 and 96 of the Saudi Arabian Royal Decree M/64, 1395/1975 provide for Notaries Public. Article 96 provides that: “Documents issued by notaries public under the powers provided in Article 93 shall have dispositive power and shall be admitted as evidence in courts without additional proof. Such documents may not be contested except on the ground that they violate the requirements of the Shari’ah principles or that they are forged”.

24. Order 24 is on revocation or repeal of the NN Rules and provision for part-heard cases which will continue under the repealed Rules.

25. There are two schedules to the Rules. The First Schedule is on forms. There are many new forms because of the new provisions in the body of the Rules. There are now 24 forms instead of the 8 forms in the NN Rules. The Second Schedule is in two parts. The Second Schedule Part I relates to allowances to witnesses while the Second Schedule relates to court fees. The notable change is that of the currency. Pound, Shilling and Pence have been replaced with Naira and Kobo.

Surprisingly, though the Rules introduced filing of briefs of argument, there is no fee provided for filing of briefs of argument by parties in the Schedule. There is also no provision on cross-appeal and consolidation. These omissions may not wait until when next the Rules will be amended. However, a practice direction may be issued to address such issues in the interim.

26. CONCLUSION

a. I must again commend the will of the Hon. Grand Kadi and his team for coming up with the GM Rules after the NN Rules was used for 59 years. The present generation of Grand Kadis has shown determination to make a difference. In just two years (2018 and 2019), the Sharia Court of Appeal in Borno, Bauchi and Gombe States have new Rules.

b. I must also commend the good work in the GM Rules. I am only able to detect very few grammatical errors. I am not able to detect any spelling or punctuation error. This is an indication of a thorough job by the committee that drafted the Rules.

c. However, there cannot be any human endeavor that is perfect. I have pointed out some of the provisions that need to be reviewed and I hope that the Rules will be reviewed soon.

d. Whenever there will be any review, a workshop should be organized like the one NBA had recently in Gombe in respect of domestication of the ACJA, 2015. The presentations at the workshop, the discussions and contributions should be collated in a report. The report should be given to any committee to be charged with the amendment of the Rules to serve as a working document. Representatives of relevant stakeholders should be included in the committee.

WORKS CITED

1. ABEBI VS. AMBALI ALAO (UNREPORTED) KWS/SCA/CV/M/IL/O2/982. Al-Kafi, Muhammad Bin Yusuf, (ND) Daar Al-Fikr, Beirut3. Al-Khayyat, A. A. I. (1999), Al-Nizaam Al-Siyaasiy Fi Al-Islam, Dar Al-Salam, Cairo.4. Al-Zahraaniy, S. D (2002) Taraa’iqul Hukm Al-Muttafa Alaihaa Wal Mukhtalaf Fiyhaa Fi Al-Shariy’ah Al- Islamiyyah, Al- Safaa Printers, Makkah.5. Bauchi State Shari;ah Courts (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2001.6. Bauchi State Sharia Court of Appeal (Amendment) Rules, 2019.7. Borno State Amicable Settlement Practice Directions, 20098. Borno State Sharia Court of Appeal Rules, 2018.9. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as altered)10. Evidence Act, Cap E14, 2011.11. FALMATA MOHAMMED KAWAR MAILA & ANOR.Vs. MALLAM BUKAR BINTUMI (UNREPORTED) APPEAL No. BOHC/MG/CA/55A/09.12. Ibrahim, Abul Wafa’ (2009) Tabsiratul Hukkaam, Al-Quds, 13. Interpretation Act, Cap 123, LFN, 200414. Sharia Court of Appeal Rules, Cap 122 Laws of Northern Nigeria, 196015. Sharia Court of Appeal Law, Cap 145, Revised Laws of Bauchi State, 1991 applicable to Gombe State.16. www.investopedia.com (retrieved 01:11:2019)17. www.saudiembassy.net (retrieved 26/11/2019)

November, 2019