Global Issues

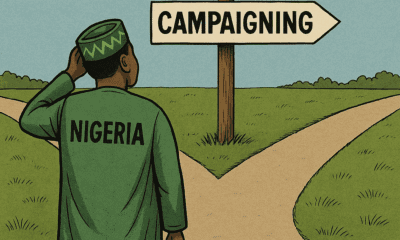

An Open Letter to British Minister Kemi Badenoch -By John Egbeazien Oshodi

In London, I see former Nigerian governors and ministers—men who looted their people—living in quiet wealth. They stroll through Chelsea and Kensington. They send their children to elite schools. They drive cars bought with stolen healthcare funds. These are men who should be rotting in jail—in Nigeria, in Britain, or elsewhere. And yet they are hosted, protected, even embraced.

I write this letter not with resentment, but with memory. Not with bitterness, but with clarity. I am a Nigerian—born of the land, shaped by its contradictions, and like you, now living outside its borders.

In 2010, during your campaign for Parliament in Dulwich and West Norwood, you made a heartfelt appeal that many Nigerians, myself included, still remember. You wrote:

“Like you, I am sick and tired of reading that Nigerians are fraudsters, terrorists, bombing aeroplanes, or slaughtering each other in places like Jos…. I am asking for your help now to support a Nigerian who will improve our national image and do something great here.”

You called Nigerians “fantastic.” You reached for our support. You built your launchpad upon the very identity you now choose to disown.

And so, when I hear you now declare that you “no longer identify as Nigerian,” when I hear you describe Nigeria as a country where “fear was everywhere” and “almost everything seemed broken,” I do not react with anger—but with sorrow. Because this is not only a public disavowal of a nation’s pain—it is a quiet betrayal of its people’s struggle.

I Understand Why You Might Distance Yourself

I say this not to judge you. In fact, I understand you—perhaps more than you expect.

I have watched the Nigerian news and felt my chest tighten. I have seen the police turned into private weapons for the elite. I have watched as courts echo orders from above, not the Constitution. I have seen entire communities silenced. I have watched students study in darkness while their leaders fly to Europe for treatment. I have watched young voices disappear for speaking out.

Like you, many of us left. We left because we were exhausted—by dysfunction, by danger, by the sense that nothing would change. We were shaped by the failures of our education, justice, and political systems. I do not romanticize it.

But unlike you, I cannot deny it. For all its brokenness, Nigeria remains the soil of my beginning. And that identity, no matter how complicated, is not one I am willing to erase. Not for approval. Not for power. Not for politics.

I wear my Nigerian name with all its history—its burdens and its beauty. Not because it is perfect, but because it is true.

The Brokenness You Describe Has Roots Beyond Nigeria

What you experienced in Nigeria was real. The trauma was valid. But I urge you now, with the weight of your position and the reach of your voice, to speak with historical honesty.

The rigid, authoritarian schools you endured as a child—the whippings, the rote memorization, the forced silence—these were not born of Nigerian culture. They were British inventions, imported and institutionalized during colonial rule. These schools were designed to produce quiet, obedient clerks for empire—not critical thinkers, not creators, not citizens.

And those systems still persist. You and I both suffered under them. But we must name them correctly.

When you call Nigeria “broken,” I ask you to remember: much of what shattered was never truly ours to begin with. And the breaking did not happen in isolation.

Ethnic rivalries. Economic sabotage. Military dependency. Resource extraction without infrastructure. These are not merely Nigerian failures. These are colonial legacies—unfinished wounds. The trauma is not just current. It is generational.

Even now, Nigerians live with the aftershocks. We live with psychological confusion, with cultural fragmentation, with mistrust in leadership, with a silence so deep that many have forgotten how to scream.

Madam Minister, You Have a Platform—Use It to Build, Not Just to Disown

You are now in power. You sit in the halls of British government. You are no longer just a survivor of Nigerian systems—you are a potential reformer of British complicity.

And what do you see from that seat?

In London, I see former Nigerian governors and ministers—men who looted their people—living in quiet wealth. They stroll through Chelsea and Kensington. They send their children to elite schools. They drive cars bought with stolen healthcare funds. These are men who should be rotting in jail—in Nigeria, in Britain, or elsewhere. And yet they are hosted, protected, even embraced.

Even Nigerian presidents—like the late Muhammadu Buhari—flew regularly to London for medical treatment, while hospitals back home crumbled. Nurses were unpaid. Medicines were scarce. Children died of treatable fevers. A two-year-old girl in Kano. A four-year-old boy in Cross River. A seventy-year-old grandmother in Benue. And you know this: all across Nigeria, they die because healthcare has collapsed—but London hospitals remain open to those who caused it.

Why are these escape routes still open?

You, Minister Badenoch, can help close them. You can support policies that block stolen wealth from entering British banks. You can name and shame those who have bled Nigeria dry. You can call for accountability—real accountability.

But instead, your words flatten the nation into a headline: “Fear everywhere. Everything broken.”

You speak of dysfunction, but not of resilience. You condemn the rot, but you forget the roots.

I Remember 2010—You Should Too

You once asked us—Nigerians in the diaspora—to believe in your candidacy. You said our support mattered. You said your success would reflect well on us all.

So what changed?

You once saw your identity as a bridge. Now you see it as a weight. You once spoke to lift a people. Now you speak in ways that make them smaller. I am not asking you to pretend. I am asking you to remember.

You did not rise in a vacuum. You rose with the help of the same Nigerians you now try to leave behind. The same people you called “fantastic” are now watching you describe them as shadows.

And you do this while Nigerian leaders continue to build mansions abroad, while foreign governments—including your own—remain complicit in shielding them. Just days ago, a U.S. commission publicly condemned Nigerian officials for financial irresponsibility. While Nigeria bleeds, its elites feast—often in foreign lands.

Where is your voice on that?

A Final Word from One with a Background in Nigeria, Living in America

I am a psychologist. I work with people shaped by broken systems—legal, educational, emotional. I understand trauma, displacement, and the deep urge to disconnect from where the pain began. I live that tension too.

But I’ve also learned that distance does not erase origin. Critique does not require contempt. And silence, though tempting, often betrays more than it protects.

So I ask, Madam Minister: if you must step away from Nigeria, do so with care. If you must speak of it, let it be with memory and truth—not just wounds. Even fractured roots deserve honest tending.

But I also know this: the answer to trauma is not denial. It is reckoning. It is transformation.

Yes, Nigeria’s leadership has failed. But Nigeria’s people remain remarkable. Especially culturally. Spiritually. Creatively. The systems are weak. But the spirit remains stubborn.

So I do not ask you to wave a flag. I ask you to be fair.

Speak with tenderness. Speak with memory. Speak with the depth of someone who has known both the sting and the shelter of home. Speak truth—but not the kind that erases. Speak as someone who once asked us to believe in her. And who, by that very asking, now owes us more than a departure—she owes us remembrance.

If you find it too heavy to embrace Nigeria, Madam Minister, I will not fault you. I know the weight of that soil, the sorrow it plants in those who leave. But I beg you—do not abandon it completely. And please, do not speak of it as if it never held you, never cradled you, never called you daughter.

Because what a beautiful, deeply cultural name you carry—Kemi—short for Olúwakẹ́mi, meaning “God pampers me.” A name from a people. A name born of language, of lineage, of longing. That name is not British. It was not given lightly. And when you disown the place it came from, you disfigure more than memory—you unravel something sacred.

This writer does not know any of the individuals involved; the focus is solely on upholding democracy, truth, and justice.

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, educator, and author specializing in forensic, legal, clinical, and cross-cultural psychology, with expertise in police and prison science, juvenile justice, and family dependency systems. Born in Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and the son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, his early immersion in law enforcement laid the foundation for a lifelong commitment to justice, institutional transformation, and psychological empowerment.

In 2011, he introduced state-of-the-art forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology. Over the decades, he has taught at Florida Memorial University, Florida International University, Broward College (as Assistant Professor and Interim Associate Dean), Nova Southeastern University, and Lynn University. He currently teaches at Walden University and holds virtual academic roles with Weldios University and ISCOM University.

In the U.S., Prof. Oshodi serves as a government consultant in forensic-clinical psychology and leads professional and research initiatives through the Oshodi Foundation, the Center for Psychological and Forensic Services. He is the originator of Psychoafricalysis, a culturally anchored psychological model that integrates African sociocultural realities, historical memory, and symbolic-spiritual consciousness—offering a transformative alternative to dominant Western psychological paradigms.

A proud Black Republican, Professor Oshodi is a strong advocate for ethical leadership, institutional accountability, and renewed bonds between Africa and its global diaspora—working across borders to inspire psychological resilience, systemic reform, and forward-looking public dialogue.