Global Issues

China’s Journey to Superpower: Lessons for Nigeria and the World -By Cynthia Moses

In adapting these lessons, Nigeria does not need to replicate China’s model wholesale. Its political system, cultural diversity, and democratic framework are distinct. But the underlying principles—strategic vision, disciplined execution, targeted investment, and inclusive development—are universally applicable. If Nigeria can internalise and apply these, it will own its transformation story.

As China commemorates the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, it does so with a profound sense of historical reckoning. From a nation once mired in poverty, rural backwardness, and colonial legacy, China has emerged as a global economic and technological power. Central to this remarkable national journey is a dual story: the pursuit of modernisation and the eradication of absolute poverty at an unprecedented scale.

When the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, the country was one of the poorest in the world. The aftermath of war and foreign occupation had left the economy devastated. Most of China’s population lived in rural areas under harsh subsistence conditions. Basic infrastructure was lacking, literacy rates were low, and disease was widespread. More than 80 per cent of Chinese citizens lived below the international poverty line, and economic life was primarily agrarian and informal.

Over the following decades, the Chinese state implemented successive development campaigns, often with mixed results. Early attempts at rapid industrialisation, such as the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, were met with minimal success. However, China’s modernisation took a decisive turn in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, who introduced market-oriented reforms and opened the economy to foreign investment. These changes marked the beginning of what became known as the “Reform and Opening-Up” era—a transformation that would fundamentally reshape the country’s economic landscape.

Over the next four decades, China underwent one of the most rapid industrial and technological expansions in modern history. Annual GDP growth averaged nearly 10 per cent for much of this period. Factories sprang up in coastal cities. Rural labour migrated en masse to urban centres. Foreign capital flowed in. Entire towns transformed into manufacturing hubs. The rise of special economic zones like Shenzhen became symbolic of the broader modernisation effort. The state heavily invested in infrastructure, education, and industrial policy, ensuring that economic gains were widely distributed, even if uneven at times.

Yet, modernisation was not pursued for its own sake. It was explicitly tied to the ambition of improving human well-being and eradicating poverty. In fact, few countries in history have made poverty alleviation as central to their national strategy as China. The government, working through both centralised plans and decentralised implementation, systematically connected economic growth to poverty reduction policies. In many regions, infrastructure development was deliberately targeted at enabling poor villages to access markets. Agricultural reforms gave farmers greater control over production and allowed them to sell surplus produce, vastly increasing rural incomes.

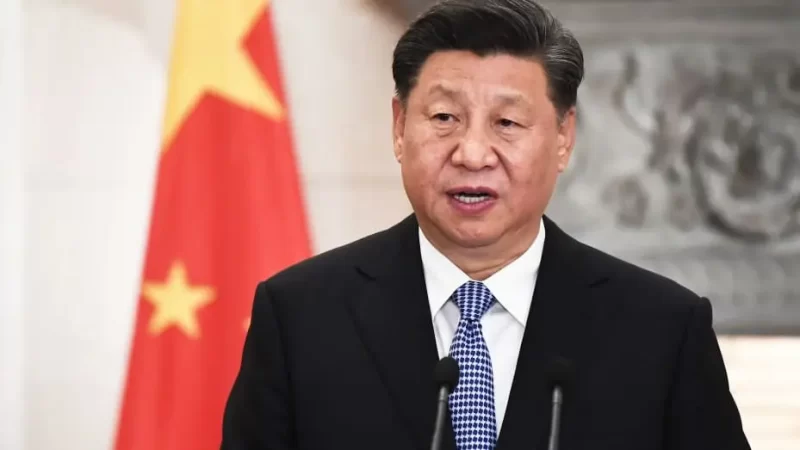

Despite these efforts, by the early 2000s, poverty remained entrenched in some areas—particularly in China’s remote, mountainous, or ethnic minority regions. At the same time, the country’s rapid economic growth had produced stark inequalities, especially between urban and rural populations. Recognising this, China began a new phase in its poverty alleviation campaign. In 2013, President Xi Jinping declared the goal of eliminating extreme poverty by 2020, an ambitious target that would define social and economic policy for the remainder of the decade.

The strategy that followed became known as “targeted poverty alleviation”, a multi-faceted approach that focused on identifying and addressing the unique needs of poor households and villages. Government officials were assigned responsibility for specific families. Data collection efforts were intensified to identify who was poor and why. Support measures were tailored accordingly—ranging from agricultural subsidies and vocational training to relocation programs for people living in environmentally fragile or inaccessible areas. The emphasis was on precision and accountability, marking a departure from broad, one-size-fits-all programmes.

By the end of 2020, Chinese authorities declared a complete victory in the fight against extreme poverty, stating that all 98.99 million people who had been living below the national poverty line since 2012 had been lifted out of poverty. Furthermore, 832 counties and 128,000 villages previously classified as impoverished were officially removed from the national poverty registry. These results were verified through third-party evaluations and confirmed by institutions including the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank, which praised the scale and speed of China’s achievement.

This feat is even more striking when viewed in a global context. According to the World Bank, over 70 per cent of global poverty reduction since the 1980s has occurred in China. The country’s contribution to human development has reshaped the global poverty map.

In absolute terms, it has lifted more people out of poverty than any other nation in history.

But China’s modernisation has not stopped at economic development or poverty eradication. In recent years, Beijing has articulated a broader vision of what it calls “Chinese-style modernisation.” This concept, heavily emphasised in government white papers and speeches, refers not only to economic indicators but also to social equity, cultural confidence, environmental sustainability, and national cohesion. It is a model that diverges from the Western template of modernisation, rooted instead in China’s unique political system, long civilisational history, and centralised policy planning.

One of the central elements of this model is technological advancement. China now leads the world in several areas of innovation, including 5G deployment, artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, and high-speed rail. State-led investment in science and education has created an ecosystem in which technological modernisation supports not only economic growth but also public services, agriculture, and rural connectivity. This approach has allowed previously underserved regions to access digital platforms, mobile healthcare, and distance learning—further closing the development gap.

At the same time, the government has transitioned from a poverty alleviation agenda to what it calls “rural revitalisation”. This shift reflects recognition that lifting people out of poverty is only the beginning. Long-term development requires sustainable livelihoods, education, healthcare, infrastructure, and community institutions that enable prosperity to continue across generations. Rural revitalisation aims to ensure that the progress achieved is irreversible.

Nevertheless, a few challenges remain. Income inequality persists, particularly between urban and rural areas. An ageing population threatens to strain public services and pension systems. Youth unemployment is a growing concern.

China’s journey from one of the world’s poorest nations to a global superpower is not without complications. Still, it stands as one of the most important development stories of the modern age. The combination of economic modernisation and poverty reduction has transformed not only the structure of the Chinese economy but also the daily lives of its people.

It is a story of planning, innovation, mobilisation, and sheer scale—one that will continue to shape the 21st century.

For Nigeria, China’s transformation offers more than inspiration—it provides tangible lessons in how to structure national development around long-term planning, inclusive growth, and strategic investment.

One of the takeaways is the necessity of long-term national planning that transcends political cycles. While China maintained decades of continuity in its development agenda, Nigeria has often struggled with policy inconsistency and the politicisation of development programmes. A focused, multi-decade plan—especially in areas like infrastructure, industrial policy, and agricultural modernisation—would provide the stability needed for sustainable progress.

China’s poverty alleviation strategy also demonstrates the power of data-driven, targeted intervention. Nigeria’s current poverty rate remains high, particularly in rural and conflict-affected regions. Rather than relying on generalised anti-poverty programmes, Nigeria could emulate China’s approach by identifying the specific causes and demographics of poverty at a household level. This would allow for precise policy responses—whether in the form of agricultural support, skills training, healthcare, or relocation assistance.

Infrastructure investment, especially in underserved rural areas, was a cornerstone of China’s success. Nigeria’s persistent infrastructure deficit continues to impede growth. Learning from China, future investments should aim not just at urban megaprojects but also at connecting remote communities to economic opportunities through improved roads, electrification, and digital connectivity.

Agriculture reform is another key area. China’s decision to give farmers more autonomy and market access significantly increased rural incomes. Nigeria, with vast arable land and a large rural population, can replicate this by securing land tenure, supporting mechanisation, and investing in agricultural extension services and rural agribusiness.

Moreover, China’s use of Special Economic Zones to attract investment and build manufacturing capacity offers a template Nigeria can adapt. Nigeria’s own SEZs have been hampered by poor infrastructure and regulatory uncertainty. A renewed focus on making these zones viable—through governance reforms and better integration into national industrial policy—could catalyse job creation and export growth.

Another critical lesson lies in the prioritisation of education and technology. China’s rapid ascent in high-tech industries was no accident—it was the product of sustained investment in STEM education and innovation ecosystems. Nigeria must similarly prioritise education, research, and digital infrastructure to unlock the potential of its young, tech-savvy population.

Perhaps most crucially, China’s success hinged on coordinated governance—clear roles for central and local governments, and strict accountability. Nigeria’s federal structure presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Building more effective collaboration between federal, state, and local authorities will be essential to translating policy into tangible outcomes.

Finally, just as China transitioned from poverty eradication to rural revitalisation, Nigeria must also think beyond survival. It must build systems and institutions that foster sustainable prosperity, equitable growth, and social cohesion. Only then can it ensure that gains made today are not lost tomorrow.

In adapting these lessons, Nigeria does not need to replicate China’s model wholesale. Its political system, cultural diversity, and democratic framework are distinct. But the underlying principles—strategic vision, disciplined execution, targeted investment, and inclusive development—are universally applicable. If Nigeria can internalise and apply these, it will own its transformation story.

Cynthia, a public analyst, writes from Abuja via cymoses93@gmail.com