Forgotten Dairies

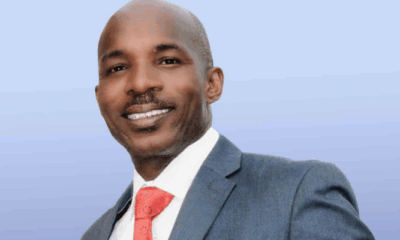

December 30 Without Olikoye: Celebrating A Health Minister Nigeria Never Replaced -By Isaac Asabor

Today, December 30, 2025 without Olikoye is more than a date on the calendar. It is a mirror, one that reflects how far Nigeria’s health sector has fallen, how low expectations have sunk, and how little justification there is for the continued decline. Until leadership is reclaimed as service rather than spectacle, the absence his birthday marks will remain not just personal, but national.

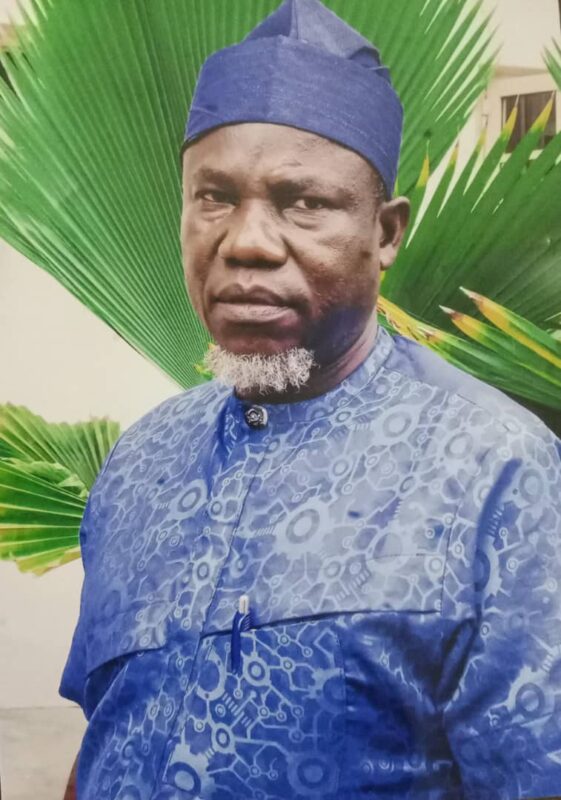

December 30 would have been Professor Olikoye Ransome-Kuti’s birthday were he alive. Instead, the date arrives each year as a sober reminder of a leadership vacuum Nigeria has never filled. It is not merely the absence of a man that this day underscores, but the disappearance of a standard, one that Nigeria’s health sector leadership has failed, or refused, to meet for more than two decades.

Ransome-Kuti was not a ceremonial minister. He did not occupy the office of minister of health as a political ornament or a reward for loyalty. He was a working minister in the strictest sense of the term. Between 1985 and 1992, he approached public health as a core national obligation, inseparable from economic development, social stability, and national security. At a time when governance was constrained by military rule and economic austerity, he insisted that the health of Nigerians was not negotiable.

What distinguished Ransome-Kuti was clarity of purpose. He understood, instinctively and intellectually, that a country unable to protect the health of its citizens was sabotaging its own future. Health, in his worldview, was not an afterthought to be addressed after “more important” sectors had been funded. It was foundational. Without healthy citizens, productivity collapses, education suffers, and poverty deepens. That understanding guided every major policy choice he made.

His record is not shrouded in myth. It is documented. Under his leadership, Nigeria’s immunization programmes were expanded aggressively, not hesitantly. Vaccination was treated as a national emergency, not a bureaucratic routine. Polio, measles, tetanus, and other preventable diseases were confronted with urgency and political will at a time when denial, superstition, and administrative inertia would have been easier paths. He chose the harder road: evidence-based intervention.

Primary healthcare was strengthened deliberately as the backbone of the system. Ransome-Kuti resisted the elite temptation to concentrate resources in a few urban hospitals while neglecting rural and peri-urban communities. He understood that no health system can function effectively if it ignores the grassroots. Clinics, not just teaching hospitals, mattered. Preventive care, not just curative medicine, was prioritized. Maternal and child health programmes received focused attention, backed by policy discipline rather than empty declarations.

He worked with limited resources and under difficult circumstances. Nigeria’s economy was under strain. External debt was mounting. The political environment was hardly conducive to long-term planning. Yet outcomes were delivered. That reality alone dismantles one of the most convenient excuses repeatedly offered by contemporary leaders: that Nigeria’s health failures are inevitable or purely structural. They are not. They are failures of leadership, vision, and seriousness.

Since Ransome-Kuti’s death in 2003, Nigeria has had no shortage of ministers of health. Names have come and gone. Tenures have begun with fanfare and ended in quiet irrelevance. What Nigeria has lacked is conviction. The office has steadily drifted from a position of responsibility into a transactional post, allocated for political balance, regional arithmetic, or party reward rather than competence, courage, or vision.

In recent decades, health policy has been reduced to performance theatre. Strategic plans are launched with glossy brochures. Committees are inaugurated. Roadmaps are unveiled. International conferences are attended. Yet hospitals continue to crumble. Primary healthcare centres remain understaffed or nonexistent in many communities. Essential drugs are unavailable. Medical equipment lies broken and unrepaired. Healthcare workers, demoralized and underpaid, migrate in alarming numbers in search of dignity abroad.

Nigeria today spends more on health in absolute terms than it did during Ransome-Kuti’s era, yet achieves less in outcomes. This is not a matter of nostalgia; it is a matter of data. Teaching hospitals that once served as centres of excellence now struggle with basic functionality. Referral systems barely work. Preventable diseases persist. Maternal mortality remains a national disgrace. Infant mortality continues to mock official statistics and political speeches.

Out-of-pocket health spending remains crushing. Millions of Nigerians are forced to choose between medical care and survival. Illness routinely pushes families into poverty. Health insurance coverage remains shallow and ineffective. These are not mysteries. They are the predictable consequences of a system governed without urgency, accountability, or moral seriousness.

What set Ransome-Kuti apart was not only expertise but character. He was blunt to the point of discomfort. He was disciplined and intolerant of mediocrity. He believed public office was a trust, not an entitlement. He demanded data, accountability, and measurable impact. He did not govern by press release or social media applause. He governed by results. That ethos, unfashionable, demanding, and uncompromising, is precisely what has been missing from Nigeria’s health sector leadership since his passing.

Ransome-Kuti did not pretend that reform was easy. He understood resistance, bureaucracy, and political pressure. But he did not allow those obstacles to become alibis for inaction. Today, by contrast, excuses have become institutionalized. Every failure is blamed on funding, federalism, population growth, or global trends. Rarely is responsibility accepted. Rarely is incompetence named for what it is.

It is tempting to romanticize the past, but this is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is an exercise in comparison. And the comparison is unforgiving. Ransome-Kuti delivered under military rule, with fewer resources and weaker institutions. Today’s ministers operate under civilian democracy, with larger budgets, international partnerships, donor support, and technological advances. Yet basic outcomes remain elusive. The problem is not complexity. It is courage.

On this December 30, remembering Olikoye Ransome-Kuti should go beyond polite tributes and ceremonial wreaths. It should provoke discomfort. It should force a reckoning. Nigeria did not merely lose a former minister; it lost a model of leadership it has shown no interest in reproducing. Until the country produces a health minister who matches his seriousness, integrity, and commitment, every birthday remembrance will double as an indictment.

Today, December 30, 2025 without Olikoye is more than a date on the calendar. It is a mirror, one that reflects how far Nigeria’s health sector has fallen, how low expectations have sunk, and how little justification there is for the continued decline. Until leadership is reclaimed as service rather than spectacle, the absence his birthday marks will remain not just personal, but national.