Entertainments

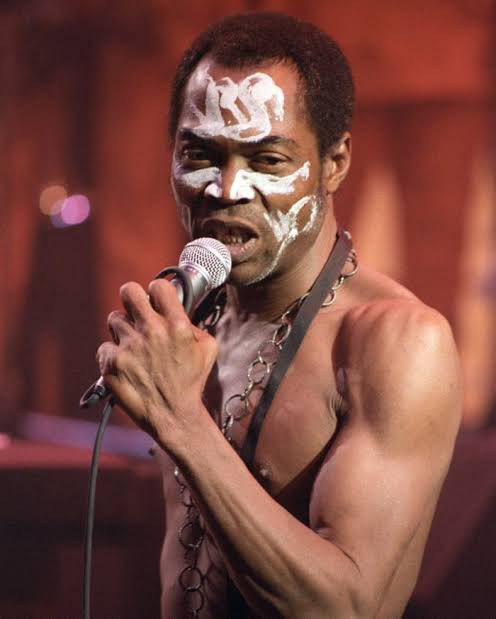

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti: The Man Whose Music Remains Iconic And Unmatched By The Modern Era -By Isaac Asabor

Artists across genres, jazz, hip-hop, rock, funk, and electronic music, have cited Fela as a foundational influence. His fingerprints are everywhere, even when unacknowledged. Entire academic disciplines have been built around his work. Broadway created Fela, not because of nostalgia, but because his life read like epic theatre. Few modern musicians, no matter how popular, can inspire that level of sustained scholarly, artistic, and political engagement.

There are legends, and then there are forces of nature. Fela Anikulapo-Kuti belongs firmly in the latter category. To compare his legacy with that of any modern-day musician is not just lazy, it is intellectually dishonest. Fela was not simply ahead of his time; he was operating on an entirely different plane of relevance, courage, originality, and consequence. His music did not beg for applause. It demanded reckoning. His life did not seek validation. It imposed meaning.

Today’s global music scene is crowded with stars, influencers, trendsetters, and chart-toppers. But none of them, none, carry the cultural weight, political danger, philosophical depth, and enduring revolutionary energy that Fela carried effortlessly, and often painfully. Fela was not just a musician. He was a phenomenon. More than that, he was a movement; one that still marches long after his death.

To understand why Fela cannot be compared, one must first understand what he was up against. Fela did not make music in safe studios insulated from consequences. He made music in a hostile state, under brutal military dictatorships, where truth-telling was punished with batons, bullets, prison cells, and firebombs. While many artists today flirt with “activism” on social media timelines, Fela confronted power face-to-face, naming names, calling out generals, mocking presidents, and exposing the rot of postcolonial African leadership with surgical precision.

And he paid for it, over and over again. His Kalakuta Republic was raided repeatedly. His mother, the formidable Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was thrown from a window by soldiers and later died from complications related to that assault. Fela was beaten, imprisoned, framed, harassed, and hunted. Yet he did not retreat. He did not dilute his message. If anything, the oppression sharpened his art. That alone already places him in a category modern musicians rarely approach.

Without a doubt, Fela’s greatness did not rest only on courage. It rested on creation. This is as Afrobeat, real Afrobeat, not the pop-friendly “Afrobeats” wave that dominates today, was Fela’s invention. He fused traditional Yoruba rhythms, highlife, jazz, funk, and African percussion into a sound so complex, so hypnotic, and so politically charged that it could not be ignored. His songs were long because his thoughts were long. His arrangements were layered because oppression itself was layered. His music was not designed for radio convenience; it was designed for liberation.

Each song was an essay. Each performance was a sermon. Each album was a manifesto. Where modern music often prioritizes brevity, virality, and algorithmic friendliness, Fela prioritized truth, immersion, and endurance. He trusted his audience to think, to listen, and to confront uncomfortable realities. Songs like Zombie, Coffin for Head of State, Sorrow, Tears and Blood, ITT (International Thief Thief), and Water No Get Enemy were not metaphors wrapped in ambiguity. They were direct indictments. Clear. Fearless. Unapologetic.

Fela sang in Pidgin English not because it was trendy, but because it was democratic. He wanted the market woman, the taxi driver, the student, and the factory worker to understand him without translation. His music crossed class lines effortlessly, something few modern artists, trapped in niche branding, can claim.

And then there was the performance. Fela on stage was not entertainment in the shallow sense. It was ritual. Sweat-soaked, trance-inducing, confrontational ritual. He did not perform for audiences; he performed with them, pulling them into a shared psychological space where music, politics, spirituality, and rebellion merged. The Afrika Shrine was not a concert venue; it was a parallel republic, a place where the Nigerian state’s authority did not apply.

Modern musicians tour arenas. Fela built countercultures. Globally, Fela’s reach was astonishing, especially considering the era he operated in, long before streaming, social media, and digital distribution. From Lagos to London, New York to Berlin, Paris to Tokyo, Fela’s music traveled on vinyl, word of mouth, bootlegs, and sheer reputation. He was studied by musicians, feared by governments, admired by intellectuals, and embraced by global countercultural movements.

Artists across genres, jazz, hip-hop, rock, funk, and electronic music, have cited Fela as a foundational influence. His fingerprints are everywhere, even when unacknowledged. Entire academic disciplines have been built around his work. Broadway created Fela, not because of nostalgia, but because his life read like epic theatre. Few modern musicians, no matter how popular, can inspire that level of sustained scholarly, artistic, and political engagement.

Crucially, Fela refused sanitization. He was flawed, controversial, contradictory, and human. He did not polish himself to appeal to Western sensibilities or local moral comfort. He rejected respectability politics long before the term became fashionable. His personal life sparked debate. His lifestyle unsettled conservatives. But even his critics understood one thing: Fela was authentic to the bone.

That authenticity is precisely what modern celebrity culture struggles to produce. Today, images are curated, controversies managed, statements vetted, and rebellion monetized. Fela could not be managed. He could not be packaged. He could not be owned. Governments could not silence him. Corporations could not sponsor him. Ideologies could not fully contain him. He belonged to himself, and, by extension, to the people.

When people say, “This modern artist is the new Fela,” they reveal a misunderstanding of scale. Fela was not a phase. He was a seismic shift. You don’t replace earthquakes with aftershocks.

His legacy is not measured in awards, charts, or streaming numbers. It is measured in courage passed down, in music that still sounds dangerous decades later, in political language he normalized, and in the audacity he made possible for future generations of African artists.

Fela taught musicians that it was possible, and necessary, to speak truth without permission. He showed Africa that culture could be weaponized against tyranny. He proved that music could be both beautiful and brutal, joyful and confrontational, spiritual and political.

The foregoing views are the reasons comparisons of Fela’s music and his legacy with any modern day musician fail. Modern musicians may be talented. Some may even be socially conscious. But none operate under the existential stakes Fela faced, and few would survive them. Fame today is often about visibility. Fela’s fame was about vulnerability, placing his body, his family, and his freedom on the line for what he believed.

Fela did not just sing about freedom. He lived it loudly, recklessly, and completely. In the end, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti was not trying to be remembered. He was trying to be effective. And that is why his legacy refuses to shrink with time. It expands. It confronts. It challenges every new generation to ask itself an uncomfortable question: “What are you willing to risk for the truth?”

Until a modern musician can answer that with blood, exile, broken bones, and unbroken spirit, the comparison should stop. Fela was not just music. Fela was history happening in real time.