Democracy & Governance

Fubara’s Journey Of Submission To Powers Bigger Than Him -By Isaac Asabor

Gone was the fiery rhetoric. In its place was a tone of accommodation, a recognition that survival in Nigeria’s political jungle requires compromise, even capitulation. That speech marked the final burial of the Fubara who once swore to chart his own path.

For close to two years, Rivers State has been the theater of a political tragedy in which Governor Siminalayi Fubara, once hailed as a defiant underdog, has now found himself swallowed by forces larger than his office, his will, and even his rhetoric.

At the outset, Fubara projected the image of a man determined to resist the overbearing shadow of his predecessor and benefactor, Nyesom Wike. He spoke tough, his words dripping with defiance. He wanted the world to know that though he ascended the governorship seat through Wike’s structure, he was no puppet. He declared that he would not be cowed, and in those moments, he won the admiration of Rivers people, and other Nigerians; including this writer, who saw him as a David daring to challenge a Goliath within his own political household.

But as the months rolled on, it became clear that the battle was not merely personal. It was systemic. The Governor was up against entrenched powers, federal influence, the legislative machinery, judicial pronouncements, and the political cunning of a seasoned godfather. His loudest cry came when he told Rivers people that his “spirit had left the Governorship position.” That was not mere resignation rhetoric; it was an admission of defeat, a realization that the forces arrayed against him were not only political but also existential.

That sentiment was echoed in his first public speech after being suspended by President Bola Tinubu and placed under emergency rule. On May 12, 2025, during a Night of Tributes for the late elder statesman, Chief Edwin Kiagbodo Clark, Fubara declared openly: “If I had my way, I wouldn’t want to return… my spirit left Government House long ago.” Those words were not offhand. They captured the essence of a man cornered by circumstances, confessing before elders, supporters, and detractors alike that the battle had drained him. He even admitted that he looked healthier and enjoyed more peace outside Government House. To many observers, that speech marked the symbolic death of Fubara’s resistance.

Then came the humiliation of a six-month emergency rule, during which a sole administrator, Vice-Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas (retd.), governed in his place. Fubara was silenced, sidelined, and stripped of relevance. Yet, when the state of emergency ended, his response further underscored how much he had been bent by the system. In a statewide broadcast on September 18, 2025, he explained why he refused to challenge the legality of the emergency rule:

“As your governor, I accepted to abide by the state of emergency declaration and chose to cooperate with Mr. President and the National Assembly, guided by my conviction that the sacrifice was not too great to secure peace, stability, and progress of Rivers State. This was why I also resisted the pressure to challenge the constitutionality of the declaration of the state of emergency.”

The Fubara who once warned that he would not be intimidated had now publicly embraced submission as a virtue. He went further to thank President Tinubu for “brokering peace,” and openly declared that he, Wike, and the Rivers State House of Assembly had all “accepted to bury the hatchet.” It was a moment of political surrender, dressed up in the language of peace and reconciliation.

Gone was the fiery rhetoric. In its place was a tone of accommodation, a recognition that survival in Nigeria’s political jungle requires compromise, even capitulation. That speech marked the final burial of the Fubara who once swore to chart his own path.

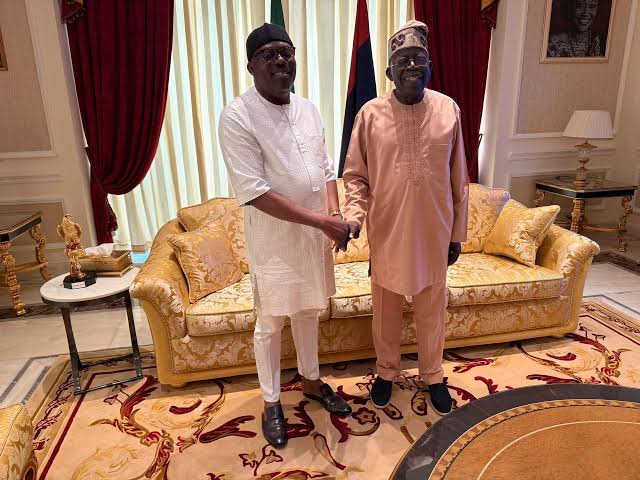

And then came the final act: on Monday, September 22, 2025, President Bola Tinubu received Fubara at the State House in Abuja. It was their first known encounter since his reinstatement. That visit was not merely a courtesy call; it was a seal of submission, a symbolic pilgrimage that underscored where real power resides. By walking into Aso Rock, Fubara acknowledged, in action if not in words, that Rivers’ political future is decided in Abuja, not Port Harcourt.

In truth, Fubara has succumbed. He has surrendered to the powers bigger than him. The forces he once resisted have now tamed him into compliance. His political journey has become a cautionary tale about the limits of individual defiance in Nigeria’s patronage-driven democracy. No matter how loud the rhetoric, no matter how strong the initial resolve, the system bends men until they break or fall in line.

Rivers people who once looked at him as a symbol of resistance must now reconcile with the reality that their governor has crossed to the other side. The firebrand who once claimed his spirit had left the office has now re-entered it, not as his own man, but as one reconciled with his overlords.

In the end, Fubara’s story is not just about one man. It is about the Nigerian federation, where state governors who imagine themselves powerful are reminded that they are tenants of a larger political estate. In his defiance, Fubara inspired hope. In his submission, he reminds us of the tragedy of power in Nigeria, that no governor, however emboldened, can withstand the convergence of godfathers, federal might, and a political system that rewards loyalty over independence.

In all of this, the greatest casualty is not Siminalayi Fubara, it is democracy itself. What has played out in Rivers State is nothing short of a desecration of democratic principles. A sitting governor was suspended by presidential fiat, a sole administrator imposed, and the so-called resolution was a coerced submission packaged as peace. That is not democracy; it is the rape of democracy, a brutal reminder that Nigeria’s political class continues to bastardize the very ideals they swore to uphold.

If the will of the people can be so easily subverted, if a governor elected by millions can be turned into a pawn by a few powerful men, then the claim that Nigeria practices true democracy becomes laughable. The Rivers saga shows us that power is not with the electorate but in the hands of those who control the levers of state. And that, no matter how it is dressed up, is not good for Nigeria’s democracy, not good for Rivers people, and certainly not good for the future of this country.