Political Issues

It Is Not a Question of If but When: Wike, Florida Mansions, and the Weight of U.S. Justice -By Prof. John Egbeazien Oshodi

The U.S. system does not operate on that currency. No mansion in America buys judicial favor; no phone call to a prosecutor halts a federal inquiry. The silence that follows initial public allegations in the U.S. is not carelessness; it is the patience of investigators assembling a record. For someone habituated to acting loudly and immediately, that quiet is an unfamiliar and punishing surveillance.

A Moment of Collapse

There are moments in a nation’s life when denial collapses under the weight of evidence. For Nigeria today, that moment has a name: Nyesom Ezenwo Wike. Former governor of Rivers State, current Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, husband to a sitting Justice of the Court of Appeal, and father to three American children whose names now appear on Florida property deeds worth significant sums.

The point of this examination is not to single out one man for personal hatred — many public officials in many countries use the same methods of concealment — but to describe a pattern, to explain how U.S. law treats that pattern differently, and to offer a calm, clinical warning about what will follow if matters are not handled with discipline and counsel. The question before us is no longer if accountability will arrive. The only question is when.

J. Signature Hotel allegedly owned by Wike

Florida Properties, Nigerian Shadows

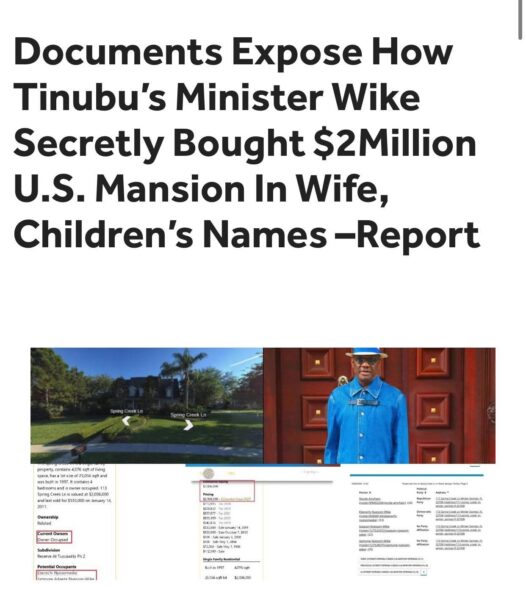

In Winter Springs, Florida, three houses stand on quiet streets. Each is titled to Wike’s children — Jordan, Joaquin, and Jazmyne — all American citizens. Each purchase, according to publicly reported records, was made with cash and transferred via quitclaim deeds, legal instruments families often use for convenience but which also enable the concealment of beneficial ownership. Justice Eberechi Suzette Wike, a Court of Appeal judge, is recorded in the paperwork as well.

Wike’s own name is not on the documents. Under U.S. law, however, the absence of a recorded name is not a shield. Investigators look for the beneficial owner — the person who funded, directed, or benefits from the asset — and U.S. statutes and practice are designed precisely to pierce the simple fiction that the name on the deed is the last word.

Channels TV Exchange: Wike Nails Himself (September 18, 2025)

On September 18, 2025, during a live Channels Television interview with Seun Okinbaloye on Politics Today, Nyesom Wike attempted to brush aside the U.S. property allegations. Instead, he may have handed American investigators exactly what they needed.

Seun pressed him directly: “You didn’t go to the houses you are said to have bought in the United States? The records are there. You don’t know what your wife and children own?”

Wike shot back: “What is my business? The houses are in their names. Which account did it pass through? Let anybody in this world say the money passed through Nyesom Ezenwo Wike or through my friend’s account.”

In trying to create distance, Wike actually exposed the pattern U.S. prosecutors are trained to pursue: cash-only property purchases, quitclaim deed transfers, and ownership placed under spouses and children rather than the official himself. He emphasized that his wife and children are Americans, as if that insulated him, but in reality it confirmed a classic money-laundering blueprint.

What Wike described as innocence — “what is my business if they own homes” — is exactly what investigators recognize as circumstantial confirmation of beneficial ownership. Those words are now frozen in the public record, available for replay not just on YouTube, but in a Florida courtroom.

Ironically, Wike did not need to incriminate himself in this way. A more disciplined approach would have been to keep the focus narrow — to say only that activist Omoyele Sowore was the one making these allegations online, while he was present to speak strictly on infrastructure and politics. That would have deflected without creating self-inflicted wounds. Instead, defiance carried him into dangerous territory, offering investigators the very thread they were hoping he would pull.

And here lies the psychological sting: Nigerian politicians are used to noise as protection — shouting down critics, mocking reporters, performing strength. But in America, silence is strategy, and patience is power. By speaking so loosely, Wike gave investigators more than documents; he gave them his own recorded words, the kind of evidence no prosecutor ever ignores.

The Legal Contrast: Nigeria vs. the U.S.

The legal contrast is stark. In Nigeria, scandals of similar shape have often produced investigations that peter out, negotiated outcomes, or political settlements. In the United States, the matter triggers a different regime: statutes like 18 U.S.C. §§1956–1957 criminalize laundering and suspicious monetary transactions, while civil and criminal forfeiture mechanisms allow authorities to treat property itself as the object of a case — United States v. [Property] — when the asset is plausibly tainted by illicit proceeds.

Practically, that means prosecutors can move on property before—or independently of—a criminal conviction. They can issue subpoenas to owners and intermediaries, demand bank and escrow records, compel testimony, and, where justified, file civil forfeiture suits that aim to remove the asset from circulation.

Psychological Trauma of Losing Control

This is not abstract law; it has existential effects on the people involved. For an official who has long operated in a system where personal influence, patronage, and material gratitude buy deference, the psychological blow is deep. In many parts of Nigeria, power has been institutionalized through material generosity: houses for judges, contracts for allies, allocations for friends.

The U.S. system does not operate on that currency. No mansion in America buys judicial favor; no phone call to a prosecutor halts a federal inquiry. The silence that follows initial public allegations in the U.S. is not carelessness; it is the patience of investigators assembling a record. For someone habituated to acting loudly and immediately, that quiet is an unfamiliar and punishing surveillance.

A Pattern Beyond One Man

It is important to be fair and clear: the methods I describe are not unique to one person. These are tools of concealment employed by many who seek to protect wealth across borders. My purpose is not to heap moralistic scorn on a single family but to explain the forensic and psychological reality they now face — and to urge disciplined, professional action.

The more pointed truth is this: placing assets in relatives’ names or using family transfers does not remove liability; in some contexts it increases it, because it expands the circle of people subject to inquiry and potential legal jeopardy.

Immediate Practical Implications

There are three immediate practical implications:

1. Civil forfeiture means property can be restrained or seized even absent a criminal verdict; the houses themselves can become the case.

2. Recorded owners — in this case, a wife and adult children who are U.S. citizens — can be subpoenaed, compelled to produce documents, and asked under oath about the source of funds and the nature of the transfers.

3. Beneficial-ownership tracing is standard: banks, realtors, escrow agents, title companies, and correspondents are all sources of documentary evidence that reveal the financial chain.

If funds were moved through escrow, wire transfers, international intermediaries, or converted via cash pathways, those traces leave metadata and institutional records that American investigators diligently harvest.

Strategic and Psychological Shifts Required

Psychologically and strategically, the person at the center of this matter must act differently than he would at home. The U.S. process rewards patience and documentation, not bluster.

The best behavioral posture is to be quiet, disciplined, and legally represented:

• Hire competent U.S. counsel immediately (both Florida counsel experienced in asset forfeiture and federal white-collar defense).

• Assemble a narrowly trusted core team to manage documents and communications.

• Preserve all records — do not destroy, edit, or sanitize documents.

• Stop public performances and contradictory interviews.

• Prepare family members to obtain independent legal counsel.

Panic, theatrical denials, or impulsive travel create documentary traces and opportunities for investigators; calm containment preserves options.

The Institutional Question at Home

There is a domestic institutional question that must also be faced. Nigerians are rightly asking why, if the facts are what they appear to be, a domestic anti-corruption agency would not at least open a clear, visible preliminary inquiry.

The Ekweremadu precedent is instructive: when Nigerian institutions contorted themselves to protect a powerful figure, foreign courts still acted. The UK proceedings were not prevented by domestic obfuscation. The lesson is simple: once foreign systems act, Abuja’s shortcuts mean nothing.

For Nigerian agencies the imperative is twofold: act transparently where you can, however constrained you feel, and document that act. Even a procedural invitation to appear for questioning — recorded, dated, and publicized — signals to citizens that the rule of law retains a pulse.

Why Nigerian Institutions Must Act First

The shame is now Nigeria’s. Citizens are already asking: why must Florida act before Abuja? Why must Americans defend Nigerians from their own leaders?

The Ekweremadu case is the most brutal precedent. In that saga, Nigerian courts and immigration twisted themselves to protect power — even ordering the release of private information about the supposed “victim.” Yet all those undemocratic maneuvers collapsed before a UK judge. Ike Ekweremadu still went to prison for nine years. The lesson is simple: once cases cross into foreign jurisdictions, Abuja’s power evaporates. No Chief Justice, no president, no minister can phone an American prosecutor to bend the rules.

If Nigerian agencies like the EFCC and ICPC fail to act, history will record their silence as complicity. Even a minimal gesture — inviting Wike to answer questions — would be therapeutic for a broken public. The absence of such action confirms the people’s darkest suspicion: that our institutions are not guardians of the law but bodyguards of the powerful.

And yet, empathy is necessary here. I have no doubt that many inside the EFCC, the ICPC, and even the judiciary want to act. They know what is right. They know what Nigerians expect. But they also know the danger: to dare might mean sudden removal, fabricated charges, or being sacrificed as an example. The political system punishes courage. Still, even within those constraints, there is room for modest acts of integrity. A small, procedural inquiry, a documented letter, or even a public invitation to account can signal to Nigerians that the rule of law has not completely died. It is precisely because the risks are real that such gestures of courage matter so deeply. I would say: before the U.S. system steps in, just be bold enough to demand — even if only “just for talk” — that a minister appear and respond. That symbolic act, however limited, is better than silence.

A Family at Risk

For the family implicated, there are human costs. A sitting judge married into this drama faces reputational and ethical consequences at home. A registered partisan affiliation in a foreign system may run afoul of domestic judicial codes. Adult children who are U.S. citizens may face legal exposure in the country they call home.

Those personal stakes should not be reduced to political theater. They require careful legal advice and psychological support. Investigations are stressful; families make mistakes under duress. Arranging confidential counseling, legal firewalls, and distinct counsel for each person named on a deed can prevent a cascade of harmful actions.

Not a Demand for Instant Ruin

This is not a demand for instant ruin. Many things may be explained, clarified, or legitimately documented. The point is this: do not gamble on delay. The U.S. system is quiet, patient, and rigorous. It will take time to assemble an airtight file; that time is not your friend if you have been reactive in public.

The strategic posture that minimizes harm is simple: silence, counsel, document preservation, and careful preparation.

Political Arithmetic and the Risk of Abandonment

There is also political arithmetic worth noting. Power is transactional. In 2023, alliances helped secure outcomes in Abuja. But political usefulness is ephemeral. The same actors who once shielded powerful men can set them aside when the calculation changes.

That is the bitter truth of politics, and it has a social psychology: when a leader is no longer indispensable, the protection fades. The person who once held influence may find himself, like many before him, suddenly exposed and materially alone — and that social abandonment is in itself a form of trauma.

Prayer Is Not a Strategy

He can pray and hope Florida never follows up — and perhaps he already is — but prayer alone is not a strategy. If U.S. federal or Florida state authorities choose to act, the consequences could be severe: seizure of assets, long and costly legal battles, reputational ruin, and potential criminal exposure.

The American system is different; it will not be deterred by local loyalty, phone calls, or domestic favors. That is a sober fact, not a threat. It should prompt a sober response: prepare quietly, secure counsel, and preserve the factual record.

Closing Appeal: Institutions and the Public

Finally, to the institutions and to the public: this moment is an opportunity to rebuild trust. A small, visible act of transparent process by domestic anti-corruption bodies — even a preliminary invitation, carefully framed and legally defensible — would be healing. It would not have to end in prosecution; it would only have to show that the rule of law still matters.

For a wounded public, those small rituals of accountability repair civic faith more effectively than grand promises.

Final Note

This piece is not a prosecution in prose. It is not a demand for blood. It is, rather, a clinical reading of what is likely to unfold and of what is required to respond with dignity and prudence. Many political actors use the same mechanisms described here. That is part of the systemic problem.

The difference now is that those mechanisms have been placed under a legal microscope that does not operate on the currency of local influence. America is not Nigeria. In that truth lies both danger and a last, slender hope: that evidence, process, and patient law can accomplish what domestic politics has so often failed to do.

About the Author

Prof. John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, educator, and public affairs analyst specializing in forensic, legal, clinical, and cross-cultural psychology. Born in Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, he has dedicated his career to linking psychology with justice, education, and governance. In 2011, he introduced advanced forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology.

He is currently contributing faculty in the Doctorate in Clinical and School Psychology at Nova Southeastern University; PhD Clinical Psychology, BS Psychology, and BS Tempo Criminal Justice programs at Walden University; Professor of Leadership Studies/Management and Social Sciences (Virtual Faculty) at ISCOM University, Benin Republic; and virtual faculty at Weldios University. He also serves as President and Chief Psychologist at the Oshodi Foundation, Center for Psychological and Forensic Services, United States.

Prof. Oshodi is a Black Republican with interests in individual responsibility, community self-reliance, and institutional democracy. He is the founder of Psychoafricalysis (Psychoafricalytic Psychology), a culturally grounded framework centering African sociocultural realities, historical memory, and future-oriented identity. He has authored over 500 articles, multiple books, and numerous peer-reviewed journal articles spanning Africentric psychological theory, higher education reform, forensic and correctional psychology, African democracy, and decolonized therapeutic models.