National Issues

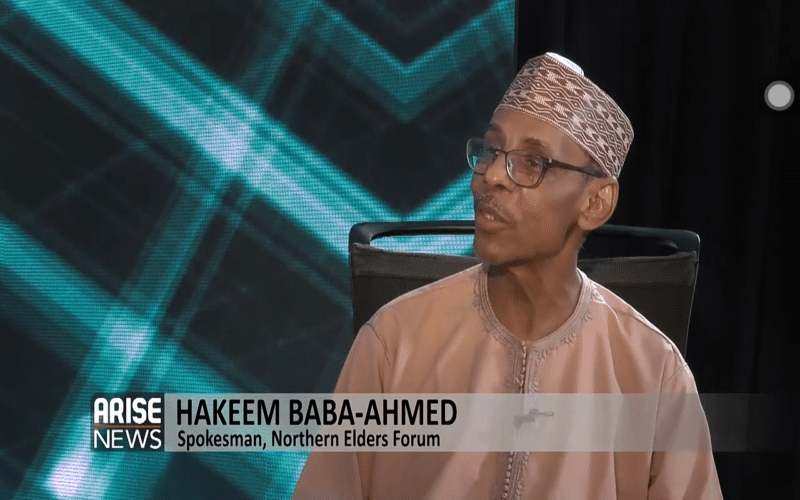

Life In A Bit Of The North -By Hakeem Baba-Ahmed

The bandits left after three hours with all seven on the list. No one knows what happened to them. In the three hours they waited, the leader of the bandits delivered a long lecture to the villagers to improve their relations with them, as nothing serious will change their situation. The villagers believed him. A few weeks ago, they agreed to send away all people who have been involved with vigilantes. The villagers now live in the hope that this is enough for a little more peace.

Over the space of 15 kilometers, 10 villages have existed for the last two or three years years completely under the control of the bandits. Their population of roughly five thousand has adjusted to a relatively new life. They belong to villagers who decided to stay put and continue an existence of sorts. Bandits who control their lives have their locations on the border with the villages. It was not an easy decision not to follow relations and neighbours who had moved as far away as they could from bandits who were forcing themselves on them as neighbours.

Moving to neighboring villages was no solution, because the bandits will, and did follow them there. Tales of villagers condemned to permanent run away from attacks have long filtered to the villagers. Relocating further to large towns was out of the question.Villagers who know only farming and keeping a few goats and sheep will find no solution to their plights in towns and cities where there are virtually no facilities for displaced families. Then, you have to consider the fact that you could lose your farm and homestead permanently if you leave without any knowledge of when you will return.They see security personnel sporadically, but only speeding past.They have not reported a case to the highly mobile security people in a long while. They could not chase away bandits planning to be settlers and their neighbours and overlords.

Actually, the bandits themselves had a lot to say in the villagers’ decision not to move. They needed the labour of the villagers. When the villages were emptying, the bandits discovered that they were losing a vital asset after their decision to settle in and around some of the villages and use them as bases for further attacks: human labour to produce food and help keep rustled livestock. Supply lines for food and fodder are erratic and becoming more expensive to negotiate with security men. Leaders of the local bandits struck a deal with the remaining villagers. If villagers stay and work on bandits’ farms and theirs, bandits will leave them in peace. Details were to be worked out later.

Details have not been worked out in the way you agree terms between equal parties. In real terms, the villagers live and work entirely under conditions dictated by the bandits. Basically, villagers first prepare abandoned farmlands now belonging to the bandit at the onset of the planting season and then move to their own farms. First, though, they pay ‘dues’ for the privilege of preparing their own farms. At every stage of the farming circle, these dues are negotiated intensely. Bandits start from millions and move down. They remind villagers that they have relations in towns and cities who are aware of their plight, and they will pay the millions demanded. The villagers routinely deny having rich relations. They also know their values to the bandit. Enforcing tough terms or millions of Naira encourage people to sneak out from villages at night, a trend that had been declining. In the end, two or three million Naira is agreed within a specified period.

Not all the money given by the villagers to the bandits is spent on buying guns, ammunition, drugs, information, motorcycles and fuel, medications and clothing. Using the intricate routes involving sellers, security people, middlemen, informers and bandits, chemicals, pesticides, fertilizer and implements are purchased by the bandits. These are also given to the villagers, or on occasions, sold to them at costs below what they will incur if they could go to markets outside the control of the bandits. In the last two or three years, this territory has seen harvests that compare well with the pre- bandit era. Cattle and other animals look well-fed. By contrast, you could travel 50 square miles from these villages without seeing a single cultivated farmland. You might see crumbling homesteads that are now regularly used as shelter or bases by bandits, but you will not see any agricultural activity. If you do see military or vigilante outposts, they are very likely to be heavily fortified, in all probability awaiting instructions to move with vehicles that have no fuel.

These villages under reference are not exactly small islands of peace at some costs. The bandits who control them value them as protection against regular forays by loud and frightening jets that periodically send bandits and villagers alike scurrying for cover. The villagers are the shields the bandit needs to avert destruction. To get them, the state has to commit a massacre. Villagers are also convenient as messengers and conduits. With the rest of their families detained by the bandit, few messengers have absconded so far.

If a visitor to these villages walks through them, he will be struck by a most unusual sight: no villager has a goat, sheep or even chicken. Or phones and transistor radio sets. Only the bandit section of these settlements have live animals of any type. There is no school in this cluster of villages. They had one many years ago, but the three teachers were abducted, released after payment of ransoms and had promptly relocated. The school now serves as residence of an extremely temperamental leader of the bandits and his assortment of relations and bodyguards.

The villages have no market in the traditional sense of a physical location where people buy and sell goods and products. Truth is, no one has anything to sell, and no one has any money to buy anything Virtually everyone lives off what they produce, and when they run short, neighbours pitch in with the little available.Bandits have money, but they get their supplies from markets and other sources far away from these villages.

There is a different life a little distance from the villages, made up of bandits usually drunk to their eyeballs or high on all types of drugs, women of easy virtue brought in from towns, musicians willing to brave it and itinerant people providing services, such as those who perform medical services, trainers on firearms and charm providers. There are also kidnapped people permanently surrounded by bandits, some as young as 14. On some nights, you will hear a mixture of music, screams and sporadic shootings. Generally, villagers are not encouraged to venture into bandit territory. Parents whose young men had long defected to the bandits wonder if their young ones are part of the merriments.

Life in the villages is regimented. Prayers are allowed, but the head bandit and advisers have discouraged call to prayers that often disturb their sleep. There are no Islamic schools or rural clinics. Women have died during childbirth. The villagers buried them quietly. There are very few young females in the villages. Forays by bandits who lined up pubescent females and young ladies and took them away twos or threes on motorcycles, sometime for weeks before they are returned, have forced parents and husbands to pay unofficial vigilantes to sneak them out of the villages at night. The few times they were caught, they were made telling examples to those who attempt to prevent or avoid being routinely gang-raped, activities the bandits approached with a pronounced sense of entitlement.

Last Sallah, the leader of the bandits donated a cow to the village. The next day, he came personally with his entourage to meet with hamlet heads of the 10 villages, their Imams and youth leaders. He had a list of seven secret vigilante members that lived among the villagers. His demand was simple: hand them over, or provide any seven persons in their place who will suffer the penalties usually reserved for vigilantes.

The bandits left after three hours with all seven on the list. No one knows what happened to them. In the three hours they waited, the leader of the bandits delivered a long lecture to the villagers to improve their relations with them, as nothing serious will change their situation. The villagers believed him. A few weeks ago, they agreed to send away all people who have been involved with vigilantes. The villagers now live in the hope that this is enough for a little more peace.