Global Issues

The Politics of Liberation: Bob Marley in Postcolonial Discourse -By Patrick Iwelunmor

Through the metaphor of Babylon, Marley diagnosed the postcolonial condition with prophetic clarity. Babylon was not just ancient scripture; it was the IMF strangling African economies, the CIA scripting elections, the apartheid regimes of the South, the ghettoes of Kingston, and the silence of churches that blessed oppression. Wonder why Kofi Awoonor talks about “A huge senseless cathedral of doom? Zion, by contrast, was not merely Africa as geography but Africa as dignity—a spiritual homeland, a reclamation of wholeness.

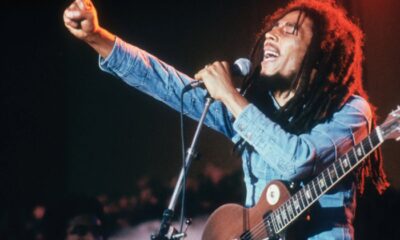

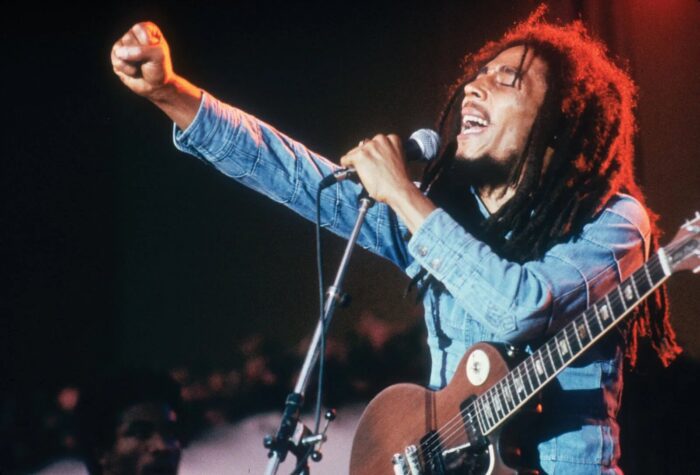

Bob Marley was not just a man with dreadlocks, a guitar, and a reggae beat. He was the conscience of a broken world, the griot of a scattered people, and the prophet of a generation still nursing the wounds of empire. To read Marley through the lens of postcolonialism is to confront the raw memory of colonial violence—wounds unhealed, histories fragmented, and yet voices defiantly rising from the ruins.

Jamaica, Marley’s birthplace, was never a natural nation but a colonial construction—an island carved by slavery, watered by blood, and policed by laws that served the Crown. Out of this crucible of exile, reggae emerged, not as entertainment but as survival. For Marley, the guitar was not an instrument; it was an axe – what Zulus call the mambazo, shattering the walls of imperial lies. The microphone was his pulpit, and his congregation was the African diaspora, still wandering, yearning for Zion.

Postcolonial theorists speak of “decolonising the mind.” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o reminds us that freedom begins not with flags but with language. Marley understood this. His embrace of Jamaican patois was not stylistic decoration—it was rebellion. It was his refusal to let the tongue of empire dictate the truth of the oppressed. In his patois, the world heard resistance clothed in rhythm.

But Marley was not naïve. He saw that postcolonialism is filled with paradox. Flags change, anthems change, but the chains remain—invisible, yet heavy on the mind. His voice in Redemption Song cuts to the marrow:

“Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our minds.”

Here, Marley echoes Frantz Fanon, who warned that true liberation is not about replacing colonial rulers with local elites, but about dismantling the structures of inferiority and greed they left behind. Marley’s fire burned not only against white colonial masters but also against black governors who became mimic men—guardians of the same empire they claimed to overthrow.

Bob Marley

This is why Marley’s songs carry both celebration and warning. When he sang Zimbabwe, he was present at the dawn of independence. He rejoiced, but he also cautioned:

“Every man got a right to decide his own destiny.”

Freedom, Marley insisted, is not a gift bestowed by leaders but a discipline embraced by peoples. In this, he aligns with Homi Bhabha’s notion of a “third space”—the fragile negotiation between imposed structures and authentic agency.

Through the metaphor of Babylon, Marley diagnosed the postcolonial condition with prophetic clarity. Babylon was not just ancient scripture; it was the IMF strangling African economies, the CIA scripting elections, the apartheid regimes of the South, the ghettoes of Kingston, and the silence of churches that blessed oppression. Wonder why Kofi Awoonor talks about “A huge senseless cathedral of doom? Zion, by contrast, was not merely Africa as geography but Africa as dignity—a spiritual homeland, a reclamation of wholeness.

Yet Marley refused to romanticize Africa. He saw its betrayals, its civil wars, its leaders who danced with empire under new disguises. His performance at Zimbabwe’s independence was both prophecy and irony: the same nation that celebrated with him would soon drown in the same tyranny it once resisted. Marley understood Edward Said’s wisdom—that the postcolonial story must be read contrapuntally, with all its harmonies and dissonances.

Jamaica itself was a mirror of the postcolonial tragedy. Politically free since 1962, yet economically captive, socially fractured, and still chained to the plantation’s shadow. Marley sang into this contradiction, wielding reggae as a counter-discourse. In War, borrowing the words of Haile Selassie, he stripped away the illusions of progress:

“Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior

Is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned…

Everywhere is war.”

Marley understood that the war was not always fought with guns. It was fought in classrooms with colonial syllabuses that erased African memory, in banks that trapped nations in cycles of debt, in the media where the West monopolized the telling of the African story.

But Marley’s genius was that he never wallowed in victimhood. He transformed lament into resistance, pain into poetry, and despair into defiance. His was a stubborn hope—a call not for pity but for courage:

“Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights!

Don’t give up the fight!”

This is why Marley still matters. His legacy is both a mirror and a map. The mirror forces us to confront our scars—the betrayal of independence, the persistence of exploitation, the chains that changed colour but not weight. The map points us toward Zion—not merely a return to Africa, but a return to truth, to memory, to dignity, to the unyielding conviction that freedom is a song we must all learn to sing.

Marley’s reggae was never accident. It was design. His rhythms carried the memory of slave ships, his drumbeats echoed the forbidden sounds of Africa, his lyrics tore down colonial myths and replaced them with truth. His voice was both balm and battle cry, wound and cure.

And so, the postcolonial struggle remains unfinished. Babylon still prowls the earth. The oppressors have changed their masks, but the system endures. Yet, in the quiet of the night, in the swell of a rally, Marley’s voice still rises, calling us to conscience, calling us to courage:

“Won’t you help to sing

These songs of freedom?

’Cause all I ever have—

Redemption songs.”

In that call lies both judgment and hope—the burden of history and the promise of freedom.