Global Issues

6 Years After Chibok: Are Our Daughters Spoils of War? -By Aisha Muhammed-Oyebode

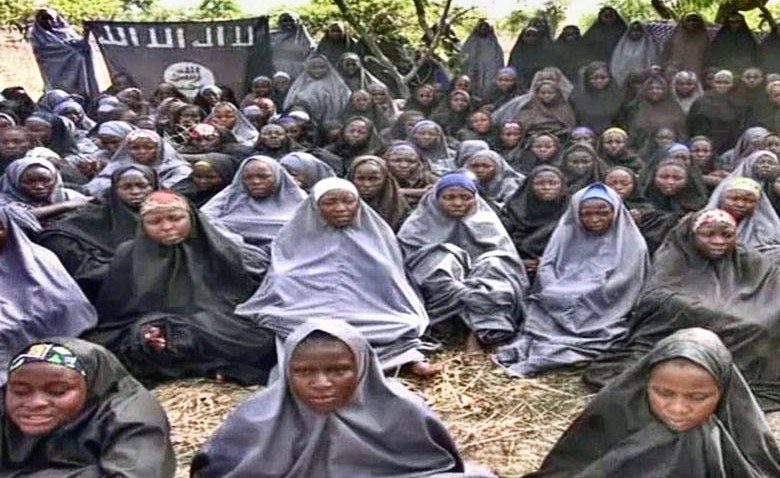

Six years ago, to the day, 276 schoolgirls went missing from the Government Secondary School, Chibok, kidnapped by the terrorist organisation, Jama’atul ahl al-sunnah li da’awati wal Jihad, known as Boko Haram. In the aftermath, we recorded elements of hope, especially with the astounding escape of 57 girls. Then we agonised for two years, a month, and a day, searching and watching in despair and horror as Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau threatened to sell the girls as slaves. Finally, on May 17, 2016, vigilantes wandering in the Sambisa Forest of North-East Nigeria found Amina Ali Nkeki. Hope was restored. Amina had been “freed,” as would the 106 girls to return after her; three by Nigerian para-military intervention, twenty-one by negotiated release in October 2016, and eighty-two more in May 2017. However, today April 14, 112 Chibok girls still remain in captivity.

Over the course of its brutal crusade, Boko Haram has kidnapped and enslaved thousands of Nigeria’s women and girls; sentencing them to radicalisation by the tenets of its extremist ideology and domestic and sexual slavery, much of it perpetrated under the umbrella of marriage. The most sadistic expression of Boko Haram’s instrumentalisation of power remains its insistence on the appropriation of female bodies as a reward for masculinity. Like a number of the kidnapped girls, some of who were as young as eleven when abducted, Amina Ali Nkeki had given birth in captivity to a baby girl, Safiya, who at the time of her release was four months old. Perhaps the youngest of the Chibok girls to be kidnapped, Amina had also returned with a third companion, Mohammed Hayatu, identified as her husband. Amina would later tell her debriefers that the Boko Haram commander who had taken charge of her early on had directed that she should marry Hayatu, and that she had no option but to agree.

Gender driven violence has been a constant hallmark of the Boko Haram insurgency in Northern Nigeria. The insurgents drill their female captives to justify their own enslavement and to believe that their brutal oppression is deserved. Upon realising that many of the girls rescued were found to be pregnant. Kashim Shettima, governor of Borno State, where most of the girls kidnapped were from, spoke of how Boko Haram’s leaders “pray before mating, offering supplications for God to make the products of what they are doing become children that will inherit their ideology.” A class dynamic was also at play. For the young underclass men that largely comprise Boko Haram’s ranks, these abductions were their only contact with educated girls. Under normal circumstances, the daughters of Chibok and others like them, would be above the station of their captors, and therefore inaccessible. It is a powerful paradox that although the nation’s initial neglect of the Chibok girls was perhaps a function of their “disadvantaged backgrounds”, by virtue of their education, they were too prized to be legitimately married off to their captors. For Boko Haram’s young men, the abductions were their means of violently bridging the class divide with girls ordinarily beyond their reach. Uneducated and therefore undesirable as the girls’ suitors, the insurgents claimed them as spoils of war.

This is not unusual. Women and girls historically absent from the battlefield have long suffered a different brand of violence during war and other armed conflict. They are systematically raped, assaulted, and otherwise victimised because of their gender, becoming the silent casualties of a culture of male honour. They endure the same traumas; unstable governments, forced migration, the bombing of their cities, as their male civilian counterparts, but they are also the targeted and silenced victims of sexual violence and exploitation. By forcing the girls into a pathological womanhood via marriage and premature motherhood via rape, Boko Haram deliberately manipulates and distorts another prized ideal of our country; the honour of its women. The victims, already suffering the mental scars of rape and sexual slavery under the guise of marriage, face acute rejection and stigmatisation. Upon return, they are derided as Boko Haram wives, and are habitually referred to as “Annoba”, meaning” ‘epidemic”, and their children as “hyenas amongst dogs.”

No doubt, the men of Boko Haram seized an opportunity with the Chibok girls not only to humble the Nigerian state, but also vent their contempt for women. Shekau’s rhetoric tapped into society’s deep-seated notions of male supremacy, linking medieval sensibilities with present-day patriarchy and worldwide gender-based violence. The same year they kidnapped the Chibok girls, Boko Haram began deploying girls as young as seven as suicide bombers and, in the last six years, has used more women and girls to carry out its attacks than has any other terrorist group in the world.

So how is it that despite the statistics and the evidence, there is an

appalling conspiracy of silence among the Nigerian populace? When girls

abducted by Boko Haram are returned as mangled bodies in body bags or

with pregnant bodies or cradling babies, why are we not more appalled by

what they had suffered? Why is there so little condemnation of this

stark and visible violence on their persons and dishonour to their

families, the community and the nation? Is it because armed conflict

undoubtedly exposes the weaknesses and embedded inequalities inherent in

state structures? It might be tempting to dismiss Boko Haram as an

outlier and its atrocities as exceptional crimes wrought by sadistic

outlaws. However, as one who has been involved in advocacy issues around

women’s rights and gender justice for decades, I find it impossible to

rigorously interrogate the ordeal of the Chibok girls without seeing it

as a metaphor, inextricably linked to the condition of women in Nigerian

society and the forces that disproportionately disadvantage us

socially, economically, and politically.

Difficult as it might be to accept, does the violence perpetrated by Boko Haram against women and girls mirror broadly the violence against women that is entrenched within the social order of the respective regions? Are we complicit by refusing to outlaw the same types of forced marriages and the inherent coercion, lack of consent, oppression and sexual servitude deep rooted within our nation’s laws and stoked by our culture? Otherwise, how it is that six years ago, terror left another fatal stamp on our nation, yet we are still unable to confront the acts of brutality by Boko Haram as the group continues to challenge our collective humanity?

It is time for Nigeria to act.

Aisha Muhammed-Oyebode is the CEO of the Murtala Muhammed Foundation and co-convener #BringBackOurGirls.