Forgotten Dairies

An Afternoon at the Table of the Ebora of Africa -By Zayd Ibn Isah

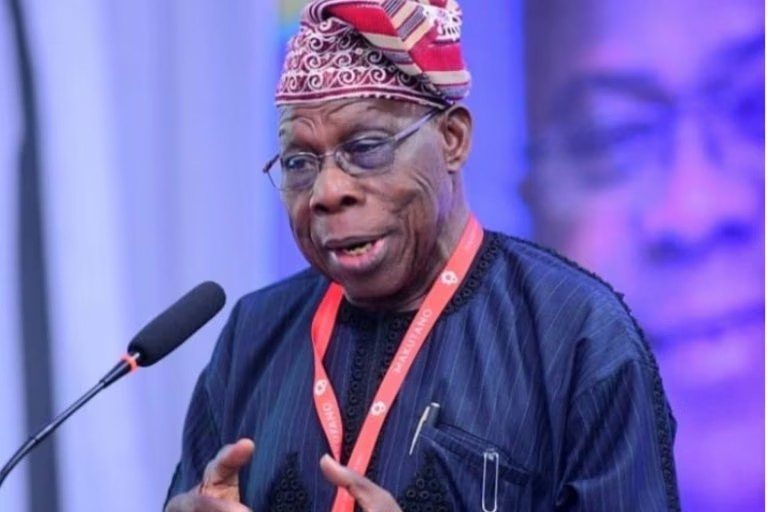

Baba Obasanjo is an enigma. At 88, he still walks with the gait and agility of a youth, alert, firm, and unmistakably present. People at that age are often confined to wheelchairs or reliant on walking sticks, but Baba remains physically and mentally imposing.

There are few Nigerians whose existence gives me as much joy and hope as Baba Olusegun Obasanjo. There are also few Nigerians whose eventual departure from this world would fill me with as much dread as his.

My friends, who know how close I am to Baba, have on several occasions advised me to hurry up with anything I want to do with him, warning that Baba may soon depart this world. I would always reply that Baba is not leaving this world anytime soon. Unfortunately, one of those friends who urged me to hurry up with Baba died recently, a young man full of ideas. His death is a clear reminder that death is no respecter of age.

Even though Baba himself has said he is heading to the departure lounge, my prayer is that he lives for many more years, because this country still needs him.

I have met Baba on two occasions. The most recent was at his palatial Presidential Library in Abeokuta, where I went to present him with a complimentary copy of my new book, for which he graciously wrote the foreword.

I arrived in Ogun State behind schedule and went straight to Ota. When I messaged Baba to inform him that I was in Ota, he replied that he does not live there, that he stays in Abeokuta, at the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library (OOPL). You can therefore imagine my joy when Baba graciously rescheduled my appointment to the following day.

The next morning, I set out from my hotel to Abeokuta and arrived after a two-hour journey, navigating the ever-busy road. The OOPL sits on a vast expanse of land. As I drove toward the White House, Baba’s residence, I marvelled at the architectural beauty of the buildings, the well-trimmed flowers, and the sheer grandeur of the complex. The library itself feels like a tertiary institution.

At the White House, the security guards questioned me. When they asked who I had come to see and I replied, “Baba Obasanjo,” surprise instantly spread across their faces, as though to say, a small boy like you came to see the Ebora of Owu? One of them, however, asked me to call Baba. I did so confidently.

When Baba answered, he called my name immediately.

“Zayd! You are in my house now?”

“Yes, Baba.”

“Wait for me.”

He hung up. That settled all doubts.

Baba had stepped out for a function elsewhere in Abeokuta. While waiting, I decided to visit the bookstore to purchase some of his books for autographing. I bought the complete three volumes of My Watch. Shortly after I returned, Baba arrived.

An elderly man was also waiting to see him. He greeted Baba warmly and followed him inside. I attempted to follow as well but was stopped because Baba had not yet seen me. I was asked to write my name in the visitors’ register, which I did. As one of the aides went in to confirm my presence, Baba was already calling me on the phone.

When I informed them that Baba was calling me inside, I was promptly led in.

I waited in the reception room for Baba to finish his meeting with the other guest. When Baba escorted his visitor out, I stood up, walked forward, and knelt down to greet him.

Baba Obasanjo is an enigma. At 88, he still walks with the gait and agility of a youth, alert, firm, and unmistakably present. People at that age are often confined to wheelchairs or reliant on walking sticks, but Baba remains physically and mentally imposing.

He took photographs with his guest and then returned to see me. I greeted him for the second time. He sat on a small dining-style reception chair at the corner of the room and motioned for me to sit opposite him, which I did.

“Zayd, you went to Ota?” he asked.

“Yes, Baba,” I replied.

“I don’t know why people associate me with Ota,” he said. “I don’t live there.”

I smiled and explained that it was perhaps because of his famous Ota Farm.

There was a brief interruption as someone came in to brief him on an issue. While Baba attended to that, my eyes wandered repeatedly to the Mancala board on the small centre table. I found myself wondering how I would explain to Baba, should he suggest a game, that I had never played it.

When our conversation resumed, I told Baba that I had bought the three volumes of My Watch from the bookstore inside the OOPL for him to autograph. He was visibly pleased and requested Volume One. He autographed it and handed it back to me.

I also autographed my own book and presented it to him. Baba praised the quality of its production. He told me he had already read the manuscript before writing the foreword and that he loved the book.

He then lamented the gradual death of the reading culture in Nigeria. According to him, if an author sells ten thousand copies of a book in Nigeria today, it is nothing short of a miracle. He advised me to take the publicity of the book seriously and to ensure a proper launch, even if only to recoup modest returns.

The icing on the cake came when he said that whenever I decided to launch the book, he would personally attend.

I did not even realise when I fell on my knees to thank him.

Baba has a long history of empowering young people. Someone once said that if I had met Baba when he was in office, I would probably have been part of his cabinet, because he has always had a deep appreciation for young people with potential.

Something else caught my attention while I was with Baba. His cook brought his food to him and spoke to him in Hausa. Baba replied fluently in the same language. Although I was not surprised that Baba understands Hausa, I was surprised that his cook is a Hausa man. Such is the detribalised nature of Baba, and the depth of his love for this country.

Baba ate his food in my presence, and it was time for him to take a nap. He thanked me for coming. We took pictures with my book, and Baba instructed his cook to serve me food, while retiring to his room. I did not wait to eat, as I was not hungry. The wonderful moment I had with Baba had already filled me with joy.

I left the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library fulfilled. After retiring to my hotel room in Lagos, I sent Baba a message of appreciation. Almost immediately, Baba called me to thank me for coming and asked if I was still in Abeokuta. I told him I had returned to Lagos. How thoughtful of him. Baba’s humility is not talked about enough.

The Igbo teach that when a child washes his hands clean, he may dine with kings. That afternoon with Baba was a living expression of that wisdom, proof that nations are sustained not merely by power, but by men whose greatness is matched by humility, and whose tables remain open to merit, memory, and hope.

Zayd Ibn Isah

lawcadet1@gmail.com