Forgotten Dairies

Gumi, Modern Fulani Herdsmen Are Not The Neighbours Nigerians Once Knew -By Isaac Asabor

For us to get it right once again, the elites among the Fulanis should speak to their people, preferably through town hall meetings across the states. Governments, in turn, should strengthen security machineries and extend their presence to rural areas. Security provision in metropolitan areas is often prioritized over rural communities, leaving villages vulnerable. Addressing this disparity is critical for rebuilding trust and restoring coexistence.

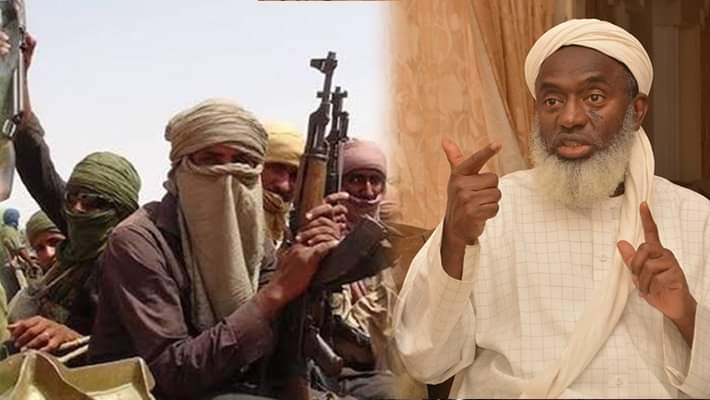

In a recent video circulating widely on social media, Islamic cleric Sheikh Ahmad Gumi urged Nigerians to “learn to live with Fulani herdsmen,” asserting that they are part of the country and that turning them into enemies would be catastrophic. On the surface, this sounds like a call for national cohesion and harmony. But a closer look at Nigeria’s realities exposes a serious flaw: Nigerians have indeed lived with herdsmen for generations, yet it is the modern-day herdsmen, largely Fulani, who have upended centuries of peaceful coexistence with violence, intimidation, and impunity.

Historically, herding and farming communities coexisted with relative harmony. Herdsmen moved cattle across territories, farmers cultivated the land, and local traditions governed grazing routes. Conflicts occurred but were manageable, resolved through communal mechanisms. Families knew when cattle would pass; farmers understood the rhythms of grazing seasons. Mutual respect prevailed.

It is sad that the typical Fulani man who we admired as children in my village in southern Edo State has today become a killer. One could recall with nostalgia how Fulani herdsmen were inspiring to children in the 1970s. We playfully imitated them, herding goats with long sticks amidst cries of “Kai, kai, kai.” The “Abokis,” as they were then called, were friendly. Those who came to our village’s four-day interval market would rent rooms for several days before returning north. They were approachable, spoke passable English, and treated villagers with respect.

Still in the 1970s, a subtle change began. Children began to dread them playfully, calling them “Ogudada,” meaning “ritual killer.” Even then, this mutual suspicion never escalated into violent conflict; the Fulani would jovially respond in kind. Fast forward to today, and one can barely imagine such interactions. Modern Fulani herdsmen have abandoned civility and respect. Attacks on villages, abductions, destruction of farmland, and mass killings are now reported across the country. If they were still in their sane and humanistic self, peaceful coexistence would remain possible.

Modern Fulani herdsmen operate with unprecedented aggression. While Sheikh Gumi frames them as Nigerians deserving protection, he omits that many have abandoned centuries-old rules of coexistence. They now live as armed factions, often disregarding laws, human rights, and basic neighborly respect. They are no longer just pastoralists seeking pasture, they are heavily armed groups whose movements are unpredictable, whose attacks can be devastating, and whose intimidation undermines governance. To treat them merely as neighbors ignores the reality: Nigerians cannot coexist peacefully with groups that have systematically violated the social contract.

Sheikh Gumi’s call for Nigerians to “learn to live together” conveniently casts the blame for discord on the victims, the communities defending their lands and lives. These communities have shown remarkable resilience, often engaging in dialogue and compromise, even as their pleas for security and justice go unheard. Nigerians have not suddenly become intolerant of herdsmen; it is the herdsmen, emboldened by impunity, who have disrupted peace.

What is urgently needed, and what Sheikh Gumi’s platform affords him, is leadership in urging his people to return to peaceful coexistence. If Fulani herdsmen are listening to him, he has the moral authority to instruct them to respect farmers’ rights, adhere to the law, and stop cycles of violence. Such guidance could save lives and restore Nigeria’s fragile social fabric.

To put it bluntly: Nigerians do not need a lecture on tolerance; Nigerians need herdsmen to learn civility. Respect for neighbors, property, and human life are non-negotiable. It is disingenuous to assert that failure to “learn to live together” is Nigeria’s fault while ignoring that many Fulani herdsmen have chosen aggression over dialogue. The asymmetry between communities makes Gumi’s argument dangerously misleading.

Moreover, insisting that herdsmen “cannot be driven out” overlooks the practical reality that communities under threat take measures to protect themselves. Citizens have the right to self-defense and to seek security from the state when the state fails to protect them. Framing this as hostility toward herdsmen, rather than a legitimate response to repeated attacks, twists the narrative and risks alienating the very people Sheikh Gumi urges to harmony.

The role of a religious leader should extend beyond protecting a group’s image; it should encompass moral instruction. If Gumi truly seeks national peace, he must publicly acknowledge that violent, lawless behavior by herdsmen is incompatible with peaceful coexistence. He must encourage restraint, accountability, and adherence to laws. He must insist pastoralists return to traditions that once allowed them to live harmoniously with farmers, rather than shielding them behind abstract notions of “belonging.”

For us to get it right once again, the elites among the Fulanis should speak to their people, preferably through town hall meetings across the states. Governments, in turn, should strengthen security machineries and extend their presence to rural areas. Security provision in metropolitan areas is often prioritized over rural communities, leaving villages vulnerable. Addressing this disparity is critical for rebuilding trust and restoring coexistence.

Nigeria is at a tipping point. The erosion of trust between communities and herdsmen threatens national cohesion. Dialogue alone, without accountability, is insufficient. Gumi’s platform gives him the unique ability to be a bridge, but he must confront the inconvenient truth: modern herdsmen, not Nigerian communities, are disrupting centuries-old peaceful coexistence. Until this reality is addressed openly, any call for Nigerians to “learn to live together” rings hollow and risks further victimizing the very communities that have historically accommodated herders.

“Learning to live together” cannot be a one-sided demand. Coexistence requires mutual respect and compromise. Nigerians have demonstrated patience for generations; the question now is whether Fulani herdsmen are willing to meet their neighbors halfway. They must respect property rights, cease attacks, and participate in structured conflict resolution mechanisms. Until they do, calls for Nigerians to accommodate violence seem impractical, and dangerous.

In conclusion, Nigeria’s problem is not that herdsmen are part of the nation; it is that some herdsmen have forgotten how to be part of society responsibly. Sheikh Gumi’s influence among Fulani herdsmen is considerable, and with it comes responsibility. He must guide his people toward civility, restraint, and respect for Nigerian laws, rather than framing the narrative in a way that absolves them of accountability. Nigerians have been living with herdsmen from time immemorial, but modern Fulani herdsmen have made this coexistence deadly and unsustainable.

Nigeria’s path to peace is simple but non-negotiable: herdsmen must remember how to live as neighbors, not as armed actors imposing fear. Sheikh Gumi, as their apologist and moral authority, has a duty to enlighten them, because if anyone can make them listen, it is him. Until then, calls for Nigerians to “learn to live together” will remain a dangerous abstraction, disconnected from the reality that continues to bleed communities across the country.