Global Issues

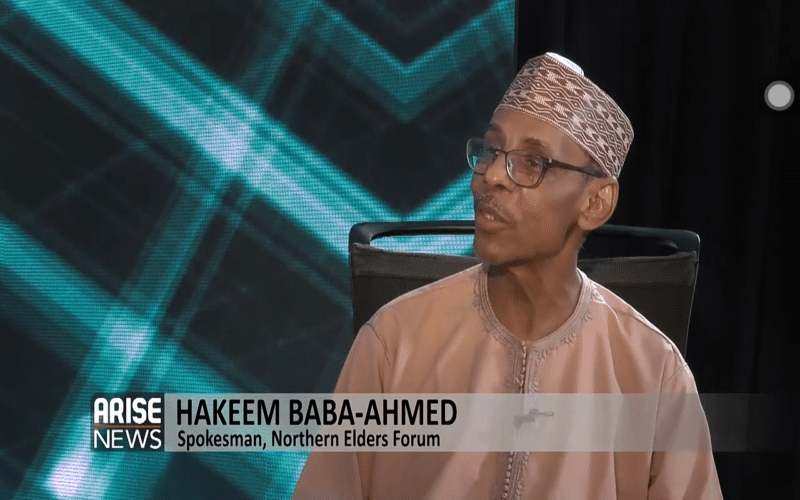

Level Heads And Informed Decisions -By Hakeem Baba-Ahmed

For Nigeria in particular, it was a particularly poor decision to threaten Niger with force because no ECOWAS expedition would even be contemplated without the active support and full commitment of Nigeria to lead it. The ECOWAS garb will never cloth the full-blown role of Nigeria. Indeed, it will be easy to believe that this is virtually a Nigerian project.

Matters have moved very fast since a few dozen soldiers sealed the official residence of Niger Republic’s president, Muhammad Bazoum. It took a few hours to establish whether we were dealing with a full-blown coup d’etat , or an uprising that could be put down in a few hours or a day or two by the rump of the military backed discreetly by French and US local military presence. It turned out to be the former. The constitutional order in West Africa’s largest and poorest country had been overthrown, again.

Niger had joined four other countries in the region to come under military rule, only a few weeks after President Ahmed Bola Tinubu, ECOWAS’s brand new Chairman had declared war on the emerging tide of non-democratic governance and terrorism in the region. President Tinubu had led the ECOWAS to set up a Committee of three Heads of State and President of the Commission to draw up action plans to arrest escalating terrorism and the creeping effrontery and assault of anti democratic forces in the region, and design strategies for quick ends to military regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea.

Initial probes into the intentions of the new military overlords in Niger suggested that they were serious over holding on to power. Citizens in the capital, Niamey trooped out in increasingly larger numbers to welcome the military. Events moved faster. France, US and the rest of the West condemned the coup and demanded a return of the constitutional order. African Union, AU, and ECOWAS followed suit. In the event that the new leaders of Niger and the local multitudes urging them on felt they had seen it all, ECOWAS slammed an ultimatum of a week for restoration of the democratic order, failing which it will dispatch a military expedition into Niger to squash the coup.

Chadian President, himself a current beneficiary of a coup, visited Niger, met and took photographs with Bazoum and left to report to Chairman Tinubu that the coup in Niger was a serious affair. Countless phone calls from all over the world demanded a restoration of the old order. On the other hand, two of Niger’s military-led neighbours and members of ECOWAS said they opposed military action against Niger. Algeria, another neighbour of Niger, said it was against military action, all the time pointing at the current state of Libya as a living testament to use of violence to affect leadership change.

Our President Tinubu and Chairman of the Commission tweaked the diplomatic option by sending former military head of state, Abdussalam Abubakar and the Sultan of Sokoto, himself a former senior military officer to Niger’s new leaders, and a former diplomat, Babagana Kingibe, to Algeria. They all came back empty handed. If there was any doubt that the military rulers of Niger were serious about resisting pressures to stand down, the messages brought back by these emissaries should have advised that the ECOWAS ultimatum was unlikely to cause a change of mind.

Citizens in Niger Republic were mobilized around the threat that an invasion, involving Nigeria’s military and others was hanging over their country. The Nigerian element was particularly played up, given the multiple layers of history, shared values, strategic interests and inter-dependence. You could hear the pitch of lamentations, unprintable language from airwaves and appeals to Nigerians not to destroy centuries of history to please foreign interests all the way from Nigerien towns to Abuja.

Niger recalled its ambassador to Nigeria, an event that would amount to sacrilege under most other circumstances. Nigeria pulled the plug on the electricity it supplied to Niger for the last five decades in return for letting the Niger river flow unhindered to Nigeria’s dams. France was dragged all over the gutter by citizens as the new rulers spoke about resistance and triumph. Russian mercenary forces active in much of the Sahel smelt opportunities to expand their presence in West Africa.

Public opinion in Nigeria was emphatic in cautioning against military activity against Niger. Popular sentiments, particularly in the North, was aghast and deeply hostile to the idea that soldiers from Nigeria and Niger could turn their guns at each other. Informed opinion was uncharacteristically emphatic on the damage that will heavily outweigh any benefit from military action against Niger. When President Tinubu wrote the Senate requesting permission to mobilize the Nigerian military against Niger in compliance with ECOWAS resolutions, Northern Senators said they will not support it. The next day, the Senate declined to grant approval for the request.

The deadline issued by ECOWAS passed without incident. ECOWAS leaders will meet tomorrow to decide next steps in dealing with Niger’s new rulers. This seems like a good time to offer advise that should have been given at the point when decisions regarding appropriate responses to the recent collapse of civil rule in Niger were being considered. First, it is right that ECOWAS should champion the democratization of the region. The damage of military rule to the growth of democratic culture in West Africa is incalculable. There is virtually nothing to show as evidence of the benefits of pervasive and prolonged stay of the military for much of the history of West Africa.

Nonetheless, ECOWAS cannot police this key and commendable goal with force. Except for the unlikely story of its brief presence in The Gambia which was relatively easily ended, ECOWAS is like a ship with multiple leaking holes. Liberia and Sierra Leone were not about democratization. As we see in the case of Niger, military leaders are unlikely to support the ouster of comrades. Ultimately, citizens who are sufficiently mobilised by the superiority and quality of the values of democratic systems over dictators are the best guarantee against non-democratic leadership.

It may take a long time to generate this type of citizenry, but current leaders of democratic West Africa can hasten the process by the quality of governance they show the citizen, as opposed to the leadership which seizes power. This, most importantly, includes the quality of elections that produce leaders. Second, the idea of ECOWAS giving the new rulers a week’s ultimatum should never have been contemplated in the first place. It exposes the leaders who offered it as totally unfamiliar with current geo-politics of the region.

The moment that ultimatum was placed on the table, all other options become merely symbolic. The idea that there is an ECOWAS out there brimming with supreme confidence over its ability to compel a change will trigger a resistance much stronger than the threat. It makes other ultimatums difficult to work, and weakens the organisation’s capacity to compel conduct, or under similar circumstances in future. It makes walking back to other options much more difficult when an ultimatum does not work.

For Nigeria in particular, it was a particularly poor decision to threaten Niger with force because no ECOWAS expedition would even be contemplated without the active support and full commitment of Nigeria to lead it. The ECOWAS garb will never cloth the full-blown role of Nigeria. Indeed, it will be easy to believe that this is virtually a Nigerian project. The Nigerian president is Chairman of ECOWAS. Nigeria did not put up its hand to mention a few reasons why it is particularly uncomfortable over a military expedition in Niger.

A Nigeria that had not rushed to make a major impression on ECOWAS and the world would have weighed its gains in affecting leadership change against what it will lose if it does contribute massively in replacing new rulers of Niger. Niger is not just any neighbour. While it cannot misbehave beyond a degree Nigeria and the world can tolerate, Nigeria’s unique and complex relationship with Niger gives it a lot more leverage to utilise to influence Niger than an entire regional group that would not step a foot into Niger without Nigeria.

It is now going to be difficult to activate a military option in Niger. What else can be done? Well, for Nigeria, the priority must be damage control. Nigeria and Niger are so connected that they can cause a lot of problems for each other. Economically, any stress in relations will impact millions of lives on both sides of the border making both sides considerably poorer. Nigeria does not want non-African interests that could offer Niger some relief at the expense of cordial relations that benefit both of us. Our historical cat-and mouse with France over influence in the region could be affected by the way we handle this problem over Niger. We should not improve the scope of Russian mercenary groups in the Sahel, or cause the French and US interests to dig in or expand to contain them. We can put Nigeriens substantially in darkness for a while.

They can interrupt the gas pipeline that should allow us export gas to the doorstep of Europe. Both of us will suffer massive setbacks in efforts to reduce the influence of terror groups in our communities and in a region that provides them near-perfect rooms for maneouvre. There are thousands of Nigerian refugees in Niger, and the Nigerian military knows how valuable the cooperation of Nigerien and Chadian military are to our fights against Boko Haram and ISIS. All in all, we need level heads when we contemplate the next steps regarding Niger Republic. Ask for release of Bazoum. Set a deadline for return of the constitutional order. Restore good relations between Niger and Nigeria urgently. Use Chad and Nigeria to influence required changes in Niger. Keep this an African affair. Learn from this episode. Africa will not know democracy until it proves better than all other systems.