National Issues

Rethinking the “Marginalisation” of the South-East -By Udo Jude Ilo

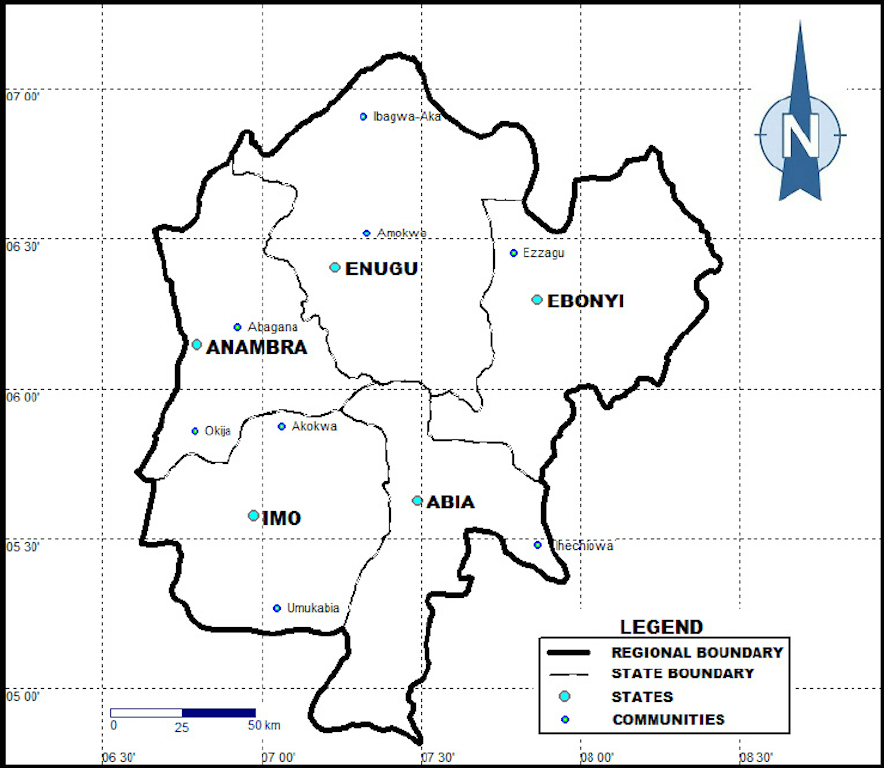

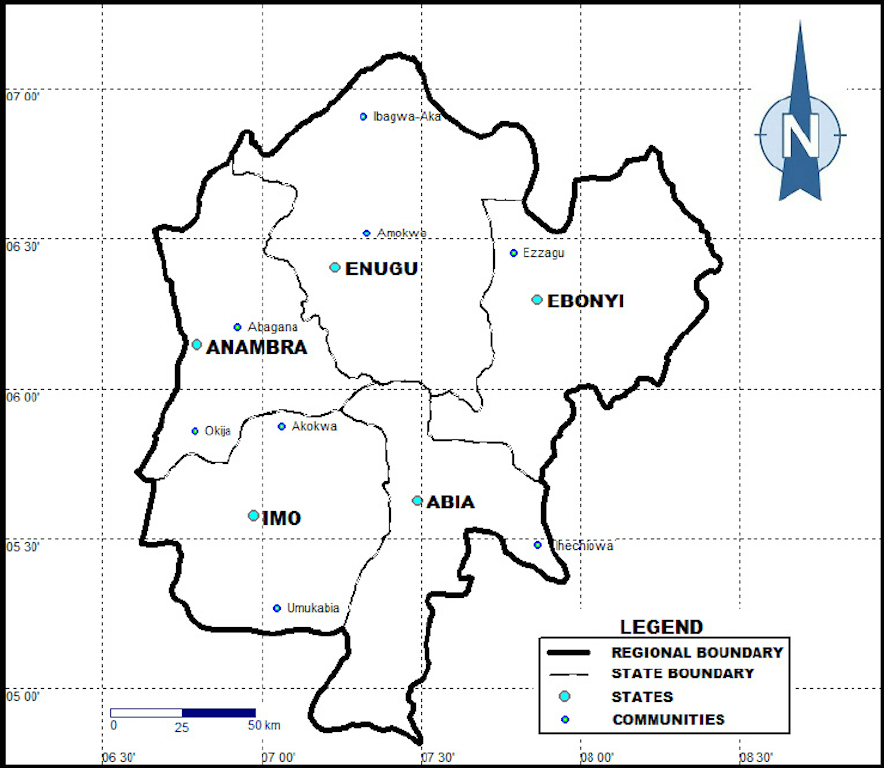

The release of Nnamdi Kanu has energised conversation around the “neglect” of the South-East and the increasing sense of isolation that a lot of youth face in the region. The feeling of victimisation has sustained the agitation for the actualisation of Biafra and a mindset that the South-East’s problem cannot be solved within the current arrangement of the Nigerian State. Olisa Agbakoba’s lawsuit against the federal republic for the injustices done to the South-East presents a legal tilt to the conversation through its meticulous documentation of the neglect of the zone and its compelling case to have these wrongs redressed. Events reinforce the growing frustration of many Nigerians, across every ethnic divide, with the effectiveness of the Nigerian State and the need for deep and honest reflection on how we can create an equitable State that gives Nigerians a sense of belonging.

Nigeria is a unique state where every tribe, ethnic group and clan claim marginalisation. It is a marginalisation that is often rooted in expectations from the state and not in obligations to the state. It is about how fat our share of the national cake ought to be and not how well we have contributed to the national cake. The mentality that Nigeria owes us so much and we owe her so little has almost nearly destroyed patriotism in the country. Understandably, the quality of governance, from the local government to the federal level, has left Nigerians with no hope, no future and no voice. The greatest disservice government has done to Nigerians over the years and which has climaxed under the current administration is the destruction of hope. Under this environment of hopelessness, our frustrations seek outlet in the nostalgia of an ‘ideal’ past or utopian dreams. We often misplace our anger and misdirect our activism.

Collectively, South-East Nigeria may have received trillions of naira since 1999. While this may pale in comparison to the resources received by other regions of Nigeria, it is, in my view, enough to uplift the region. Sadly that has not been the case. The quality of government in most of the states in the South-East in the past 17 years has been anything but sterling. However, the greatest tragedy is not the unfortunate visionless leadership that has blighted the region but rather the docility of the citizens of the South-East in tolerating these set of leaders. The comparison here is not that we have done better than some regions but that given our immense human resources, we cannot excuse the quality of leadership we produced or our inability to hold them accountable. As important as it is for us to demand our fair share from the Nigeria State, we must first live up the guiding philosophy of our forebears – Ana esi na uno amara mma puwa iro, meaning that charity begins at home.

Under Chapter 2 of the 1999 constitution, it our duty to hold government accountable not only at the federal level but also at the local level. What mechanisms have we put in place to ensure that local governments in the South-East are performing their constitutional functions for the benefit of the community? How have we held our state governors accountable? How are our resources being managed? Politicians are happy when we trumpet marginalisation at the national level while overlooking the rot that is perpetrated at home. They distract us by making us believe that our problems are from Abuja. We find reasons to demonise the Nigerian State very quickly without paying close attention to the missed opportunities that face us at home. The greatest source of marginalisation of the South-East are her leaders. Even when they occupied influential positions to right the ‘injustices’ against the region, they had been more involved in self ‘packaging’ than watching out for the people they represent.

We cannot address national marginalisation without confronting economic and political marginalisation imposed on us by our leaders in the South-East. The inability of our governors, over the years, to work together and develop an economic plan for the region that harnesses our local strength and uniqueness is inexcusable. The sacking of non-indigenes from the civil service by the government of Theodore Orji in Abia State was embarrassing – an example of how we destroy ourselves. Those were individuals whose only crime was that they are not from Abia State. This kind of discrimination within a block that claims the same ancestry demonstrates the complicated nature of our challenges and questions the rationale in locating our problems mainly at the federal government.

It doesn’t matter what restructuring we achieve or what autonomy we construct, as long as we cannot get involved in how we are governed at the local level, our marginalisation will persist. The Nigerian State is deeply flawed but not enough to assume that we cannot lift our people and, by extension, lift Nigeria. It is in my view a deeply flawed argument to assume that autonomy solves our problem or that Biafra will wave a magic wand that would take away our foundational inadequacies. We need to do more than just agonise about what could be but must focus more on what is possible within our troubled system. There is urgent need to interrogate the Nigeria project. I firmly believe that Nigeria’s diversity is actually its greatest strength. However, we cannot gloss over the wounds of the past nor the systemic marginalisation that has been wrought on the South-East. As true as this may be, the South-East is much bigger than just a victim. It must look inwards to address its internal inadequacies and build a unified platform that will enable it to take its rightful place within the Nigerian project.

Udo Jude Ilo is a Nigerian and writes as a citizen.