National Issues

The True Price Of Tradition: A Cultural Autobiography On Female Genital Mutilation And The Inherent Value Of Girls -By Cherechi Nwabueze

To gain a more objective and comprehensive understanding of female genital mutilation, it is crucial to engage with diverse perspectives and voices, including those of affected communities and individuals. This is essential to remove subjectivity when assessing the issue of female genital mutilation. It is crucial to recognize that FGM is a complex problem with social, cultural, and historical roots that affect both men and women.

Introduction: Eons ago, in Nigeria, a girl child’s worth was measured by the number of material possessions that her circumcision could fetch. Ten bags of rice, two kegs of wine, and a few cowries were the expected value, with the circumcision being a prerequisite. This outdated tradition confined girls to a life of silence, early marriage, and childbearing. Her existence was confined to the kitchen and the inner room, where she had to battle for her life, pushing out babies with nipples still buried in the lips of her nursing infants. She continuously faced and had to endure numerous challenges, including complications during pregnancy or childbirth, with limited access to education and economic opportunities.

However, as civilization has evolved, the girl child has refused to remain stagnant. She desires to be valued for her potential, not her body. She yearns to be heard and understood, just like her brothers, and to be more than society has traditionally allowed her to be. With access to quality education, healthcare, and the eradication of harmful traditional practices such as female circumcision, the girl child in Nigeria can achieve greatness and build a better future for themselves and their communities. The girl child should be allowed to break free from the shackles of the past and given the chance to reach her full potential.

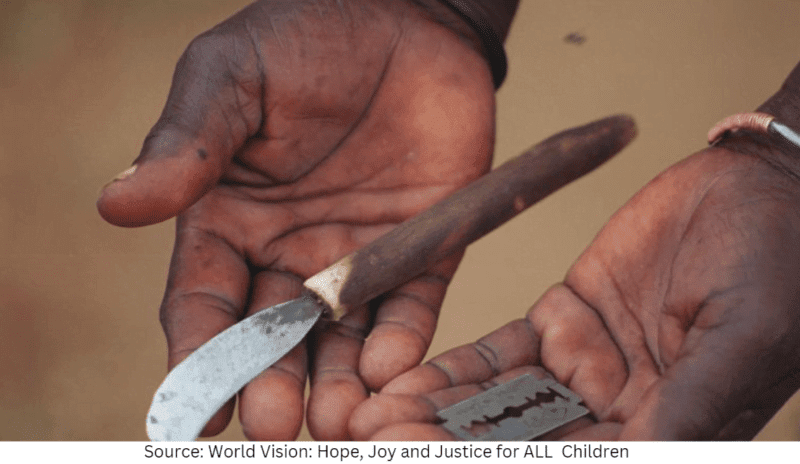

Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria: Female genital mutation (FGM), also known as female circumcision or traditional female surgery is a widely practiced cultural tradition in Nigeria that is deeply ingrained in the population’s ritual and sociocultural context 1,2. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FGM refers to all procedures that involve the partial or total removal of external female genitalia and/or injury to the female genital organs, for non-therapeutic reasons 3. The practice of FGM has been a source of enormous and bitter international controversy since the late 1970s. The debate often reaches an impasse between two well-meaning but seemingly irreconcilable positions: cultural relativism and universalism 1,3. Cultural relativism argues that FGM is a cultural tradition that should be acknowledged and respected by outsiders, whereas universalism views FGM as a violation of human rights regardless of cultural background or tradition 1,3.

Although contemporary anthropologists aim to gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of cultural practices that are now the focus of ethical, legal, and moral debate and acknowledge the difficulties involved in developing cross-cultural understanding, the practice of FGM remains prevalent in Nigeria 3,4,5. FGM is a widespread practice in Nigeria, with an estimated 19.9 million women and girls in Nigeria having undergone the procedure. This makes Nigeria the third-highest country in the world for the practice of FGM 6. Disturbingly, there are increasing rates among girls aged 0-14 from 16.9% in 2013 to 19.2% in 2018, with high prevalence in Ebonyi, Ekiti, Imo, Osun, and Oyo. Shockingly, nearly 3 million girls and women would have undergone FGM in these States in the last five years. 6

Cultural Perspective on Female Genital Mutilation: Growing up in Nigeria meant being exposed to the deeply ingrained cultural practice of female circumcision, which perpetuated gender inequality and discrimination against girls. Despite the community’s vibrant communal life, being a girl child meant facing the burden of a harmful tradition that threatened her physical and mental health. Why are girls subjected to such a painful and harmful procedure? This injustice and violence have ignited a fervent passion for advocating for the rights of girls and women. It is deeply concerning considering the negative impact of female circumcision on girls’ physical and mental health, as well as their opportunities for education and healthcare. Female circumcision is a harmful tradition rooted in deep cultural beliefs that prioritize the value and well-being of men over that of women, reinforcing gender stereotypes and systemic oppression1-3. Girls and women have the right to live free from harm and discrimination, and to have equal access to education, healthcare, and opportunities to succeed and thrive.

Despite extensive research, the origins of this practice remain unknown 3. However, it is evident that FGM is still prevalent in both urban and rural communities 2,3. The most significant reason for the continuation of this harmful practice is that it is an ancient tradition and is considered normal 3. Female genital mutilation is used as a way to welcome girls into womanhood after their first menstruation, and girls who are not subjected to FGM are often stigmatized in the community 2. The practice is sustained for various reasons, including the preservation of chastity and purification, family honor, hygiene, esthetic reasons, protection of virginity and prevention of promiscuity, modification of sociosexual attitudes, increasing the sexual pleasure of husband, enhancing fertility, and increasing matrimonial opportunities 3,7,8. However, these reasons are contrary to the limiting health effect of female circumcision 2,3,6. Although not all men may support FGM, it is still a product of traditional laws instituted by male leaders, while women are sustaining the practice to “protect” the future of their girl child, especially because of the significant value accorded to being married and the social prestige the practice brings to the family 2,3.

Unfortunately, little thought is given to the fact that the procedure has no health benefit for the girls and has potentially long-term negative implications, including violating their bodies and depriving them of the opportunity to make independent decisions about their bodies 2,3,6. Moreover, girls who undergo FGM are at risk of various health complications, such as infection, shock, damage to the urethra or anus, chronic pelvic infections, vulvar adhesions, perineal lacerations, prolonged labor, and death 2,3,8.

Addressing the Ethical and Cultural Influence on Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria: The plight of the girl child on her long walk to freedom cannot be ignored. If she remains trapped in the practice of FGM, we all are not truly free. To address this deeply ingrained issue, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary 2. Achieving social change within the community through collective, coordinated efforts to abandon the practice of “community-led action” is essential 9. Legislation in Nigeria, combined with health education, improved health literacy, and efforts to empower women, have been instrumental in the fight against the harmful practices of FGM 2. Education and raising the social status of women have been identified as key factors in reducing the prevalence of FGM2. However, it is important to acknowledge that cultural beliefs and traditions play a significant role in the continuation of FGM, and addressing this cultural background is essential to achieve significant progress in eradicating the practice.

It is important to acknowledge that personal biases and perspectives can shape the understanding and approach toward the issue of female genital mutilation (FGM) 10. For a woman who is passionate about women’s rights, it is important to recognize that FGM is not exclusively a woman’s issue; men are also significantly impacted by it and a comprehensive intervention must address this dynamic as well 9,11. For instance, some men may consider uncircumcised women as undesirable partners for marriage, which can exert pressure on women and girls to undergo the procedure against their will. Moreover, men often serve as guardians of tradition and can benefit from the perpetuation of gender inequalities and power imbalances that are reinforced through the practice of FGM. While it is acknowledged that FGM is a form of oppression towards women and girls, it is important to recognize that tradition and culture often hold greater sway on behavior than the law 2,3. This can lead to the marginalization and oppression of women and girls, ultimately harming entire communities. Additionally, it is important to recognize that one’s personal values and norms may differ from those of other girls in the community, and may lead to unintentionally perceiving one’s own beliefs as superior. This could lead to a biased view of other girls and affect their interaction with them. As a result, it may be a struggle to fully understand and empathize with girls who have undergone FGM. Therefore, it is crucial to approach them in a culturally sensitive manner, using appropriate terminology that does not cause offense or alienation 1.

To gain a more objective and comprehensive understanding of female genital mutilation, it is crucial to engage with diverse perspectives and voices, including those of affected communities and individuals 11. This is essential to remove subjectivity when assessing the issue of female genital mutilation. It is crucial to recognize that FGM is a complex problem with social, cultural, and historical roots that affect both men and women 3. Therefore, understanding the cultural influence of both males and females on FGM is critical to comprehensively addressing the issue and creating meaningful change 12. Moreover, recognizing the dynamic and contingent nature of cultural knowledge is necessary to understand the continuous influence of social, political, and economic changes on FGM practices 3. Also, it is crucial to approach FGM with an open mind and a willingness to learn from the experiences of others. Asides from counteracting personal biases and preconceived notions that may hinder progress toward ending the practice, actively seeking out and listening to the experiences and perspectives of those who have undergone FGM, as well as those who work to end the practice, will lead to a deeper understanding of the social, cultural, and possibly the historical roots of FGM 9,11. This can inform more effective strategies for ending FGM and promoting gender equality and human rights.

Finally, let us honor our female ancestors by ensuring that their struggles were not in vain and that future generations can live in a world where gender equality is a reality.

References

- Lane SD, Rubinstein RA. Judging the other: Responding to traditional female genital surgeries. The Hastings Center report. 1996;26(3):31-40. doi: 10.2307/3527930.

- Okeke T, Anyaehie U, Ezenyeaku C. An overview of female genital mutilation in Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 2012;2(1):70-73. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.96942.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Female Genital Mutilation. 1998.

- Taylor JS. Confronting “Culture” in Medicine’s “Culture of no culture”. Academic medicine. 2003;78(6):555-559. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00003.

- Smith-Morris C, Epstein J. Beyond cultural competency: Skill, reflexivity, and structure in successful tribal health care. American Indian culture and research journal. 2014;38(1):29-48. doi: 10.17953/aicr.38.1.euh77km830158413.

- UNICEF. UNICEF warns FGM on the rise among young Nigerian girls. 2022. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/unicef-warns-fgm-rise-among-young-nigerian-girls#:~:text=The%20prevalence%20of%20FGM%20is,%2C%20Imo%2C%20Osun%20and%20Oyo.

- Worsley A. Infibulation and female circumcision: A study of a little‐known custom. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1938;45(4):686-691. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1938.tb11160.x.

- De Silva S. Obstetric sequelae of female circumcision. European journal of obstetrics & gynecology and reproductive biology. 1989;32(3):233-240. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(89)90041-5.

- Panter-Brick C, Clarke SE, Lomas H, Pinder M, Lindsay SW. Culturally compelling strategies for behaviour change: A social ecology model and case study in malaria prevention. Social science & medicine (1982). 2006;62(11):2810-2825. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.009.

- Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney. “Native” anthropologists.1984.

- Wang R. Critical health literacy: A case study from China in schistosomiasis control. Health promotion international. 2000;15(3):269-274. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.269.

- Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(10):e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294