National Issues

Otodo-Gbame: Uprooting the Poor in the Name of State Progress -By Immanuel Ibe-Anyanwu

When heavily-armed security operatives escorted bulldozers to overrun Otodo-Gbame, a waterfront community in Lekki, Lagos, an entire community housing thousands of inhabitants was leveled to ruins, with many lives lost. After two grueling evictions in late 2016, residents had obtained a court order halting further demolitions. But while appealing the order, government invaded the community in a last-ditch eviction, breaking the rule of law and the lives leaning on it.

Two years after, Otodo-Gbame, now sand-filled and rid of blood and wreckage, is ready for new development. Pillars are projecting, fences rising. At one end of the land are mixers, pay-loaders, and other construction machinery chugging to the rhythm of work. Renamed Periwinkle Estate, it will host luxury homes, with plots selling from N45 million to N200 million, an amount far beyond the reach of former residents.

“We are scattered everywhere”, says Matthew Akanji, a youth leader in the defunct community, on the whereabouts of the evictees. “Some are still in Lagos, others in Ibadan. After the demolition, we no get nothing — no compensation, no resettlement.” An indigenous Lagosian, Akanji is now without a permanent abode, his family split and kids out of school. Although government adduced security and environmental blight as motivations for the demolitions, findings contained in Public-Private Connection in Urban Displacement, a recent report by the Lagos rights group SPACES FOR CHANGE, suggest state collaboration with the popular chieftaincy Elegushi family, towards gentrification.

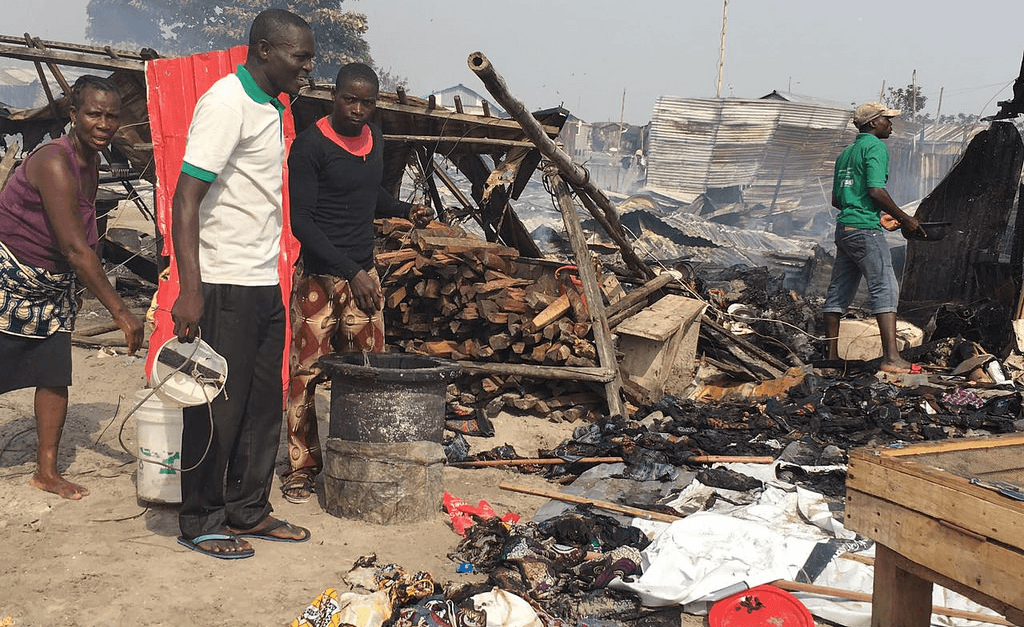

Otodo-Gbame residents after the demolition of their homes.

In October 2016, the Elegushi family had won a court suit contesting ownership of the land. Akanji says Otodo-Gbame inhabitants came originally from Badagry, settling on the land over 50 years ago, claiming a deed of occupancy predating the Land Use Act of 1978, empowers his people to stay there. Besides the court ruling vesting ownership of the land in the said family, the Lagos State House of Assembly also passed a resolution supporting the ruling. “Our only crime is that our land is in a choice area and we don’t have money”, he laments.

In its handling of the eviction exercises, government breached the evictees’ fundamental rights to dignity, habitation, and life. Having designated such settlements as illegal, government holds that evictees are not entitled to compensation or resettlement, never mind the attendant human suffering. State laws do not expressly authorise remediation where claimants do not have applicable legal or title rights. However, the SPACES FOR CHANGE report says that the state is constitutionally obligated to humanise such eviction exercises through meaningful engagement with the affected persons, payment of compensation and the provision of alternative accommodation, especially for the most vulnerable. Evidence shows that these steps were not followed. Forced evictions not only threaten the security of the victims but also pushes them deeper into homelessness and poverty, in the end defeating the original intent of reversing the urban sprawl, the report further adds.

After the devastation of Otodo-Gbame, Akanji led a group of his people to a riverine community in Ajah, where they were accommodated by its owners, the Abele-Oje family. It is a swamp overgrown with hyacinths and other coastal flora, dotted by shanties held aloft water by wooden stilts. From dry earth where coastal deposits constitute an eyesore, wooden footbridges lead to upraised homes. There are wooden canoes tethered to stilts, floating on water grey with filth. Being out of school, many of the children have taken to fishing. But beside this patch of land is ongoing commercial dredging, threatened by and threatening human occupation. Heaps of dredged sand rise in pyramids that highlight spatial constraints. With the presence of dredging machinery and trucks moving around to load sand, another confrontation looms.

“Already them don give us quit notice. You can see, some people don already comot”, Akanji says, pointing at wooden studs that once lifted shacks now absent. “Them (the dredgers) give us compensation to pack our things. Four thousand naira each (N4,000). But we don’t know where else to go.”

Leading to the settlement is a short road running from the Lekki-Ajah expressway, revealing the area’s vulnerability to state developmental interest. On both sides of the road are homesteads in sickening disrepair, and people unmistakably living in poverty. “Them don already start to de build gutter. People think say government wan’ do road for them. Na road wey bulldozer go follow enter them de build”, chirps Akanji, laughing mischievously, as he walks me to my car.

A 41-year-old father of three haunted by losses, he remains a jolly fellow, sometimes detached from his fate. “I be electrician. For Otodo-Gbame, them burn my shop where I de also sell electrical fittings. Everything don scatter. But I thank God sha I still dey alive. Many people died. We get their records, all their names, eleven of them. One woman carry pikin for back enter swamp wan’ run when police de shoot. She drown with the pikin”. Most of the dead drowned likewise while fleeing the havoc unleashed on the community. There have been no arrests for the arson and deaths that followed the clampdown, even as residents accuse the police of open and secret complicity.

Such has been the fate of a people placed beneath the law, deemed unworthy of living in Lekki. They have been uprooted by State progress. The State had a duty to develop the city, the evictees the right to exist, each party wielding a valid argument. Except that there was no dialogue, only monologues, as might buried compassion in the execution of state duty. Urban development carries a moral dilemma of evicting the poor and vulnerable as some form of urban sanitation, like eliminating disposable dirt blocking profit and city aesthetics.

For the evictees of Otodo-Gbame, it was sorrow, tears and blood, paving the way for a “Lifestyle to live”, the slogan of Periwinkle Estate. Although the past has been buried in piles of money, memory preserves knowledge of blood in the foundation of this new Estate. Memory of late Avonda Elijah, Aya Daniel, and many others cut down to erect a pack of swanky structures. As construction activities held sway at one end of Periwinkle Estate, two men squatted at the other end, taking a dump. Though unintended, the twin defecation seemed a symbolic moral rebuff at the 10-storey twin towers proposed on the land. Named “Oxygen”, the twin towers bear an ironic, if obscene, name that denotes exactly what was denied those hapless evictees now rotting in the ground.

Immanuel Ibe-Anyanwu is a freelance writer based in Lagos.