National Issues

Ajaokuta : A Story of Nigeria, Not of Efficient Steel Milling -By Feyi Fawehinmi

As you’ve probably seen in the news, steelmaking in Britain is facing an existential crisis. After losing about £5 billion in total, TATA are understandably fed up and have now thrown in the towel.

There are many reasons why this is the case but, ultimately, the current price of steel in the market just doesn’t support steelmaking for a lot of countries.

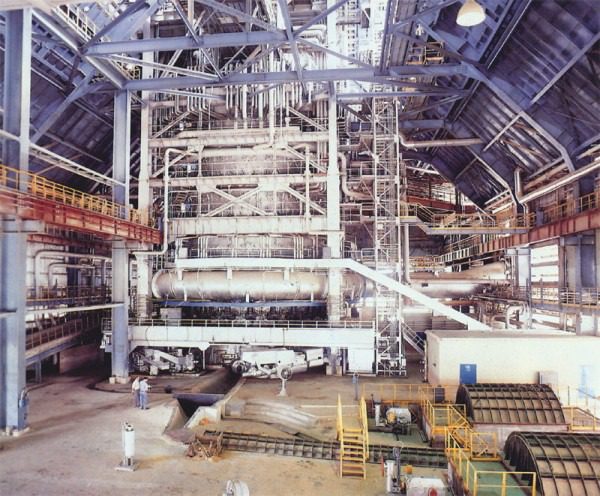

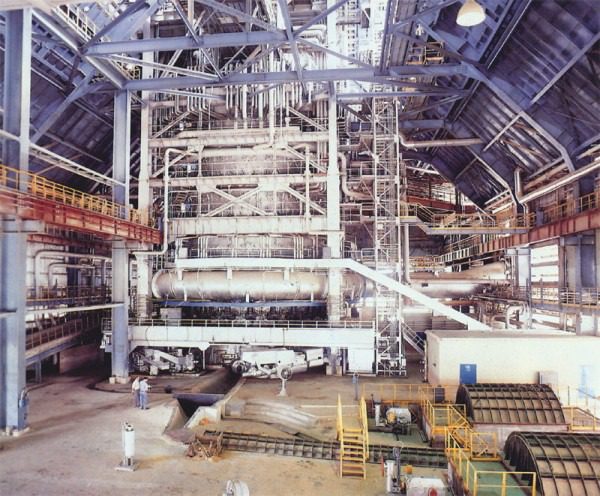

Anyway, three years ago, I wrote about Ajaokuta and how the main issue was a technological problem — the blast furnace technology. Here’s the Financial Times:

“A blast furnace also represents a huge overhead cost because, once fired up, it typically runs for six to 10 years, giving an operator little flexibility. If it is shut down prematurely, cooling damages the brick lining.”

A funny story I heard some years ago was that some manager at Ajaokuta turned off the blast furnace one time because it was wasting energy or something. And… well, you know the rest.

Today, I was roaming the internet and stumbled on a very interesting report that details the origin of Ajaokuta and how it came to be. The report itself, written in 1988, is here. But here’s the part that jumped out at me immediately:

“Two suitable zones were defined: the coastal zone stretching for about 10 kilometres between Forcados and Port Harcourt and the central zone of the country along the banks of River Niger south of Lokoja for 50 kilometres to Onitsha.

Eleven possible locations in these areas were distilled down to three: Warri, Onitsha, and Ajaokuta.

The report recommended Onitsha on the premise that the use of local ores would save precious foreign exchange.

Political factors outweighed the economic considerations, although the reasons are a matter of conjecture. The preliminary report was submitted for consideration in 1974: 3 years after a civil war in which the eastern zone of the country (with Onitsha its boundary and trading capital) attempted to break away and set up a separate nation. With the memories of the war and its scars still fresh, the authorities might have hesitated to site a project of such huge cost in Onitsha. Also, the security of government property and the safety of incoming workers from other regions of the country could not be guaranteed.

In other words, the decision was economically suboptimal but, perhaps, politically justifiable. We suggest that it is no use pretending that non-economic factors are irrelevant. In fact, they tend to be decisive in developing countries, so policy analysts must seek to accommodate them. In contrast, the decision on technology seemed economically sound. The main groups involved were the main contractor (TPE of the USSR), the Nigerian engineers (NSDA), and the consultants to NSDA (SOFRESID of France).”

Read the whole report if you can (or you can jump to page 25, where it starts to get interesting). It’s quite fascinating and perhaps unsurprising that the thing is the giant white elephant that it is today. Read it as a story of Nigeria and not so much about steel.

Here’s one other part:

It appears Nigeria trained engineers to work on the plant in India while trying to build the plant based on Soviet technology. The whole thing was a mess as the Soviets weren’t familiar with the technology that the Indian trained Nigerians demanded in the design.

It reminded me of the story of how the South Koreans built POSCO as narrated by Joe Studwell in How Asia Works:

Such is life.

Feyi Fawehinmi, a qualified accountant, has worked in the UK’s financial services industry in banking, asset management and insurance.