Political Issues

Replacing Nigeria’s Patrimony of Oil With the Politics of Hope -By Kingsley Moghalu

The real test of strategic economic nationalism will be how long it takes Nigeria to achieve a diversified industrial economy that can support the value of its currency and reduce the structural impact of dependence on commodities. This is the crucial task that faces Mr. Buhari’s cabinet. For the factors that weigh on Nigeria’s economic prospects are largely political constraints, which create incentives for officials to pursue mis-guided policies.

For too long, Nigerian leaders have acted as though the only decisions they had to make concerned who should get what. When Muhammadu Buhari, the newly elected president, announces his ministerial appointments at the end of the month, he should make clear that his government will follow a different course. He and his colleagues have the power to improve the fortunes of all Nigeria’s people.

Africa’s most populous country faces huge challenges. Its economy, which is also the continent’s largest, has been battered by external shocks, which have been amplified by its excessive reliance on crude oil revenues. As oil prices have fallen, several states became unable to pay workers’ salaries and have had to be bailed out by the federal government.

Unemployment is high, and growth is faltering. After security, engineering a turnround is the greatest challenge for the Buhari administration.

In part, the country’s troubles reflect its failure to save up for a rainy day when oil prices were high. Foreign reserves have been eroded and the country’s currency, the naira, has been devalued twice in the past year.

It also reflects the country’s excessive reliance on volatile natural resources markets. Yet efforts to diversify Nigeria’s economy are hamstrung by the parlous state of its infrastructure. Consider the electricity sector, which generates only one-tenth the amount of power produced in South Africa, in a country that has more than three times as many people. Remedying this shortfall provides an opportunity for foreign and domestic investments.

To make this happen quickly and ensure sustainability, much of the emphasis should be on off-grid renewable energy; Morocco provides the model.

The Nigerian central bank has recently taken measures to control the depletion of foreign reserves, imposing strict controls on foreign exchange transactions in order to prevent the currency from falling further. That has led many in the financial markets to question central bank’s independence; JPMorgan, the US investment bank, removed the country from its Emerging Markets Government Bond Index earlier this month, citing a lack of liquidity in the foreign exchange market.

Oil patrimony is the result of an unimaginative politics, which assumes that government cannot do anything to enlarge a country’s economy, and that its only role is to divide the spoils. Politicians have therefore concentrated on rewarding their supporters — and as the bounty has diminished, that debate has become more and more bitter.

Yet the central bank must demonstrate that it is independent, not only from the government, but also from vested private sector interests, including investors. Although some observers believe that JPMorgan’s action will force foreign investors to sell billions of dollars worth of bond holdings, the extent of the damage may be overstated. (China and India have both sustained years of impressive growth despite never having been listed in JPMorgan’s index.)

Even so, there is no doubt that Mr. Buhari believes the state should play a big role in managing the economy. He has so far proved reluctant, for example, to abolish wasteful petroleum subsidies, apparently believing that to do so would hurt the poor. He is wrong about that. The subsidies overwhelmingly benefit the rich and the middle class. Mr Buhari would achieve far more by doing away with them, and targeting the resulting savings at conditional cash transfers to the indigent.

The real test of strategic economic nationalism will be how long it takes Nigeria to achieve a diversified industrial economy that can support the value of its currency and reduce the structural impact of dependence on commodities. This is the crucial task that faces Mr. Buhari’s cabinet. For the factors that weigh on Nigeria’s economic prospects are largely political constraints, which create incentives for officials to pursue mis-guided policies.

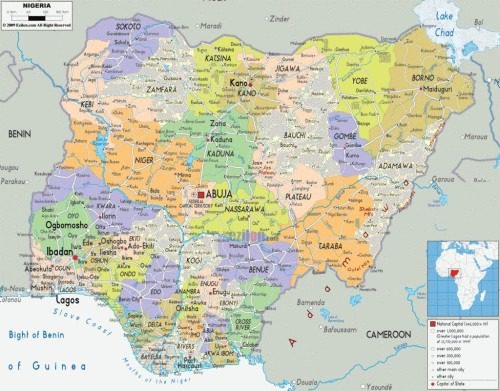

Mr Buhari needs to devolve more powers, responsibility and accountability to the constituent parts of Nigeria’s federation. The federal system, which concentrates too much power in the capital, Abuja, has proved dysfunctional and remote from the people it is supposed to serve. Constitutional amendments are needed to create incentives for economic activity.

Oil patrimony is the result of an unimaginative politics, which assumes that government cannot do anything to enlarge a country’s economy, and that its only role is to divide the spoils. Politicians have therefore concentrated on rewarding their supporters — and as the bounty has diminished, that debate has become more and more bitter.

This politics of oil must be supplanted by something more enlightened. The buck stops with Mr. Buhari, but he cannot bear the responsibility alone. He and his government must set Nigeria and its people on a new and more prosperous course.

Kingsley Moghalu, a professor at The Fletcher School at Tufts University, was a deputy governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria.

This piece was first published in Financial Times on September 21, 2015.