Forgotten Dairies

Why 6th July 1967 Should Matter To All Nigerians -By Henry Chukwuemeka Onyema

More than one hundred years after the War between the States, as the American civil war is properly called, the conflict remains an uncomfortable but recognized presence in American national psyche. The same applies to quite a few other harrowing intranational conflicts. Our problem in Nigeria is that we feel the discomfort but refuse to give the recognition.

Today I was in class with my JS 3 pupils and I told them there were two significant dates in July they should master as History students. Almost to a man, they figured out the first date before I announced it; 4th July, the date USA won her independence from Britain. Though I filled in the details they were rather at home with the idea of American independence in 1776, even though they fought a war.

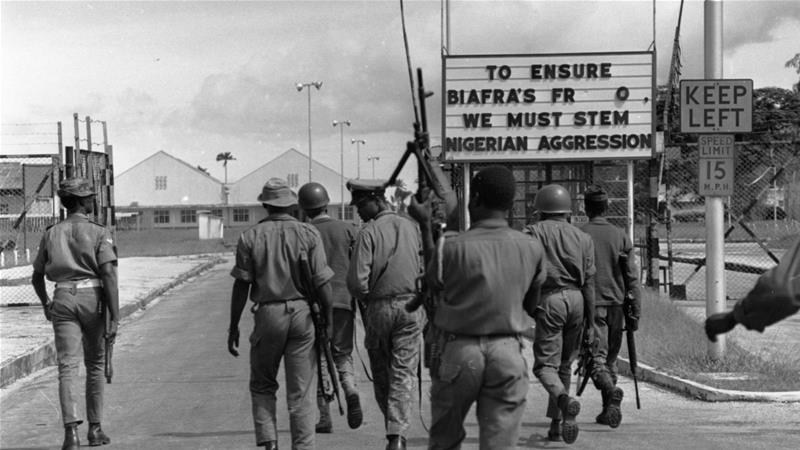

The second date was pretty much like something out of Martian lore: 6th July 1967, when the Nigerian civil war began with an onslaught by Nigerian forces against the Biafran army at Garkem, a small town near Ogoja in present-day Cross Rivers state. Talk about a twisted sense of national values. In a way the situation represents the reality that success has many followers, even in foreign climes. Hence the almighty USA’s Independence Day matters to non-American children but the date of arguably the biggest event in the history of their worse than unpleasant mother country means nothing to them.

Throughout today, I have been mulling over that war. I am an Igbo, from the ethnic group that dominated the break-away Republic of Biafra whose secession from Nigeria on 30 May 1967 triggered off the war. I belong to the generation that experienced the war in relays. This statement is deliberate: the civil war is in the consciousness of most Igbo and other Eastern Nigerians, though to varying degrees. Note, this does not mean being knowledgeable about the war. More than fifty years after the guns fell silent the civil war still bears a rather thick veil for many Nigerians on either side of that conflict, despite what is known, despite the books, novels, archival materials, movies, documents and documentaries. This is not surprising.

More than one hundred years after the War between the States, as the American civil war is properly called, the conflict remains an uncomfortable but recognized presence in American national psyche. The same applies to quite a few other harrowing intranational conflicts. Our problem in Nigeria is that we feel the discomfort but refuse to give the recognition. And till that is done, the ghost of the civil war will assail Nigerians long after the generation who witnessed firsthand how and when Nigeria stopped turning from 1966 to 1970 become part of the ages.

What does it actually mean to recognize the Nigerian civil war as far as Nigerians, especially the post-1970 generations, is concerned? These suggestions may help.

First, difficult as it is, let those who have the responsibility of distilling knowledge about Nigeria’s past strive for objectivity and truth in dispensing information about that fratricidal conflict. The civil war did not just break out because groups of backward tribesmen declared open season on each other. Certain factors led to the stubborn and bloody birth of Biafra. Can we tell the truth, at least to the best of our knowledge? A difficult task, given even the most educated Nigerian’s inclination to be ethnocentric about the most basic fact. Can we research? Can we revise age-old opinions? Even when we present facts can we present them in a spirit of sympathy devoid of the-other-side-is evil mindset?

Second, the fact is that many of the gentlemen who defeated Biafra on the battlefield are either significant players or influencers of our national political estate, despite their advanced years.eg. President Buhari. Whether they have shed their war-time disposition to the ‘rebel side’ is doubtful. They have arrogated to themselves the role of custodian of Nigeria’s national unity as if God ordained the unity and anyone challenging it deserves divine retribution. However, the fact that they have mismanaged this ‘gem’ since 1970 and thus bear great responsibility for the growth of young generations of Nigerians for whom this unity has no appeal because it has no future in stock for them has not sunk into these supposed elder statesmen. To them, Biafra is a long-rotten corpse. To these younger ones, Biafra holds a large breath of life. In the midst of these contradictory positions, what actually does the civil war mean?

Third, so much demonization of both sides of the war fills the air that its lessons remain unlearned, more than fifty years on. Nigeria’s economic and financial managers will do well to learn how Obafemi Awolowo, Nigeria’s Finance Commissioner during the war, ran the war-economy without borrowing externally.

Compare that with our current deluge of Chinese loans. Biafra’s technological innovations, bureaucratic efficiency and information dissemination capabilities were and still remain ignored. After all they were the ‘rebels.’ That is why the post-1970 generations remain largely unconvinced that Nigeria cannot breathe without foreign economic and technological oxygen.

Reconciliation is incomplete. It is half-hearted, even non-existent in many situations. I salute General Gowon’s 3Rs policy at the end of the war: reconciliation; rehabilitation; reconstruction. But Gowon’s successors did not go further. Which is unsurprising, given the antecedents of his two military successors: Generals Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo. Otherwise if the reconciliation had gone far enough, Ojukwu would have had at least a military formation named after him in Northern Nigeria before his death. (I doubt if any formation is thus named after him in the Nigerian military till date:

I stand to be corrected). Ojukwu for the record was the first indigenous quarter-master of the Nigerian army and commander of the Kano-based Fifth Battalion during the January 1966 coup, a position in which he played significant roles to quash the putsch. Otherwise Benjamin Adekunle, the commander of the Nigerian Marine Commandos, will get himself at least a portrait in war attire at the decrepit War Museum in Umuahia. Otherwise, the Asaba Massacres will be remembered yearly as a solemn, national soul-searching event, and not taken off air when any media programme seeks to discuss it. If all these and other steps had been taken over the years, successive generations of Nigerians would have learnt how to come to terms with the war and why our unity as a country matters.

Finally, how can the Nigerian civil war not remain an albatross around our necks when supposedly national leaders carry out national statecraft with war-glasses on? Secession is not synonymous with the Igbo or even Biafra. Remember Isaac Boro’s Niger Delta Republic in February 1966? Remember the North’s threat to secede following the 1953 call for independence by Anthony Enahoro at the Parliament? The bad blood created by the South’s proposal, sponsored by Enahoro, and opposed by the North, led to the bloody Kano Riots and subsequent British conference for their Nigerian colony. Remember the bloody July 29 1966 coup of Northern troops who were barely restrained from breaking up Nigeria by vested interests? Their latter-day descendants are the Nnamdi Kanus and Sunday Igbohos. What is it about Nigeria that makes secession attractive? Why do many groups feel alienated from Nigeria? Maybe if that war really mattered in our national discourse, successive leaders would seek a Nigeria which most Nigerians will see as home.

Granted, there will always be a minority. They exist, even in USA, who desire to revive the Confederate states and call for the secession of Texas. But even the maverick President Trump never sent the FBI after them. National policy is so accommodating that it pays the descendants of the former separatists to ally with the Union.

If nothing else comes to Nigerians from that troubled period, maybe we can dust the details of the Aburi talks in January 1967 and utilize it as a blueprint for national coexistence.

May the souls of all Nigerians who died between 1966 and 1970 continue to sleep in peace. Let their blood help us build a viable Nigeria, a confederation if need be.

Henry C. Onyema is a historian, teacher and author. Email: henrykd2009@yahoo.com