National Issues

Almajirinci: Why It Shouldn’t Be About Destitution and Neediness -By Majeed Dahiru

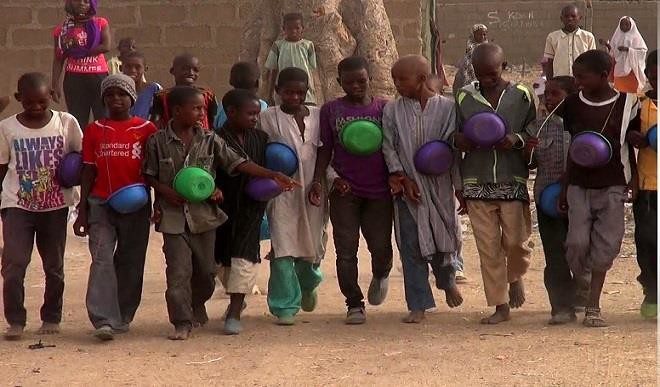

The renewed conversation about the menace of destitute and roaming around out-of-school children, in numbers estimated at 14 million in the predominantly Muslim North, has once again thrown up the unresolved question of the relevance of the traditional Almajiri system of learning in modern Nigeria. This growing army of homeless, hungry, barely clothed and uneducated socio-economically dislocated children is already an exploding time bomb that can no longer be rationalised on the basis of the pursuit of Islamic religious knowledge. Having pondered on the human tragedy that is the menace of out-of-school children, which has unfortunately been bestowed the traditional religious bona fides of an “Almajiri institution”, I have decided to share some aspects of my childhood experience growing up as a Muslim, in a Muslim family and in a predominantly Muslim community.

I was born in Okene, the homestead of Nigeria’s ethnic Ebira people of Kogi State in North-Central Nigeria, to a five generation Muslim family of prominent Islamic scholars. Looking at the numerous mosques adorned with minarets and capped with domes that dot the entire landscape of Okene and environs, from which five times a day the voice of the muezzin is heard intermittently blaring out calls to the Muslim faithful to obligatory prayers, one may not realise that the religion of Islam arrived here only less than two centuries ago. Islam had earlier reached the old Kanen Borno Empire in the present North-Eastern corner of Nigeria as early as the 11th century and in the ancient Hausa city states of Nigeria’s North-West by the 15th century, from the Muslim north of Africa.

However, the successful repelling and crushing of invading Muslim Fulani jihadi forces from the Emirate of Bida around 1885 by an alliance of Ebira tribal warrior chieftains, in an encounter recorded in oral history as “ireku ajinonoh” (Ajinomoh wars), delayed the arrival of Islam in Ebira land from the 19th century to the early 20th century. The existence of a strong guild of blacksmiths amongst the Ebira people of Okene, whose excellent iron smelting skills qualifies as one of the most advanced in black Africa, provided superior weapons to a war-like people who were famous for their mastery of archery. And with a rugged mountainous terrain, which proved treacherous to the invading calvary of horse men from the Emirate of Bida, the Ebira warriors who were fighting from mountain tops secured a decisive victory when they routed the enemy under a hail of burning spears and arrows.

Following the failed military expedition of what would have amounted to compulsory conscription of my ancestors into the religion of Islam by Jihadi forces through conquest, annexation and forcefully incorporation of their lands into the Muslim Fulani Sokoto Empire, Islam, a religion of peace, eventually arrived in Ebira land through the peaceful Da’wah mission of Islamic scholars from the nearby Ilorin Emirate. Within a few years of its arrival in Okene town, the religion of Islam was to spread fast, with majority of the people willingly and without compulsion converting from being animists to Muslims.

Over a century-and-a-half later, Okene is today a predominantly Muslim town with most families having an Islamic heritage spanning five generations, which has seen a near absolute substitution of ancestral traditions, customs and norms with puritan Islamic Prophetic traditions, as evident in the deeply religious way of life of the people. In addition to the general Islamic way-of-life of the people, Okene subsequently emerged as a leading centre of learning and dissemination of Islamic religious knowledge in northern Nigeria, having hundreds of mosques and Madrasahs located in every nook and cranny of Ebira land, which over-the-years have groomed individuals from childhood to adulthood in literacy in Arabic, for Islamic studies. Thus begins my Almajiri story.

The term ‘Almajiri’ is a Hausa corrupted version of the Arabic root word, ‘Al-muhajirun’, which connotes a migrant (student, scholar, worker), etc. And because the Quran, the hadiths and other ancillary sources of the tenets and practices of Islam are written in Arabic, a minimum level of literacy in this language that is important to our faith, is required of us Muslims. This requirement necessitated a religious culture of young children leaving home to study Arabic and Islamic studies at the feet of prominent Islamic scholars in Hausa land and the Kanem Borno areas. It is this class of children that were originally referred to as Almajiri.

However, unlike in the days of old, I didn’t have to migrate from my place of my birth to fulfil this basic requirement of minimum literacy in Arabic language for Islamic studies and religious practices. Desiring of a good life for me, just like every other responsible parent, my father simultaneously enrolled me, at the age of four, in a catholic mission primary school (one of two private schools in the whole of my community), and a Madrasah located right inside my family compound, under the supervision of my grand uncle, Mall Sadiku. Every morning on week days, after the morning meal at 7:00 a.m., I would leave for school and by 1:00 p.m. closing time, I was headed back home. After my afternoon meal, I would then follow my father to the mosque for the Zuhr congregational prayers, after which I walked into the adjoining building that served as our Madrasah, to commence the day’s business.

Like me, other children in the community were simultaneously enrolled in the formal school system, as well as in the nearest Madrasahs to their respective homes, by their parents or guardians, who similarly fed, clothed and sheltered them with care and love. Significantly, my grand uncle and teacher, Mall Sadiku didn’t have to send us to the street to beg for alms for his sustenance, because as a certified Arabic and Islamic scholar, he was a equally gainfully employed public school teacher, whose dedication to imparting knowledge in us was just an act of Ibadah (worship), with the expected reward in the hereafter.

By the age of six, I could read and write in simple English and Arabic, and was due for progression to the next stage of studying the Quran. To this end, I was transferred from the Madrasah in my family compound to a nearby Quranic school that was a walking distance of less than 100 metres from home, and under the tutelage of another prominent Islamic scholar, who like my grand uncle, was also known as Mall Sadiku. My new teacher was a strict disciplinarian who, unlike my grand uncle, wasn’t going to indulge me in any way and he made me work hard at my Quranic studies. Throughout my studies at the feet of the newer Mallam Sadiku, who was not paid a kobo by my parents or those of others for his invaluable services, and who never sent any of us under his care out on the streets with begging bowls for alms and food. The few times some of our parents brought food items as sadaqa to the Madrasah, it was usually shared among all children, including those from whose homes the charity came.

This was because Mallam Sadiku was a self-respecting and hardworking tailor who eked out a living making garments for people. My beloved Mallam Sadiku, who was married to one wife, with whom he raised a small family, would usually seat behind his sewing machine peddling for his income from morning till late afternoon, when he would then take a break to say his prayers and thereafter supervise our studies. And from his modest income, Mall Sadiku was able to feed, clothe and shelter his family, while also sending his own children to formal institutions of learning to acquire education. Discernably, Mall Sadiku deemed his dedication to our religious studies as an act of worship, which would be rewarded in the hereafter.

Beyond the Madrasah, I thereafter furthered my Arabic and Islamic studies in a publicly funded secondary school, which had the provision for a rich curriculum on the subject. To God be the glory, I eventually made a distinction in Islamic Religious Studies in my West Africa School Certificate Examination – a feat I attained without having to roam the streets of Okene, hungry, homeless and destitute. I have subsequently built on my strong Almajiri foundation to continuously develop myself into a better Muslim throughout my adult life.

Therefore, the menace of 14 million out-of-school children, attached to the supervision of a religious leader, while given the honorific of an “Almajiri institution”, is the unique dysfunction of a northern Nigerian Muslim culture, which holds education in contempt, and is without parallel in the larger Muslim world. The human tragedy of 14 million out-of-school children bonded to destitution does not qualify to be described as an Almajiri institution, but rather an oppressive system that can best be designated as a crime against the humanity of these children by their parents and a society that condones such evil of irresponsible parenting. A rudimentary knowledge of Arabic and Islamic studies is only for the purposes of enhancement of the practices of the Muslim religion that should never be a substitute for education or skills acquisition, as they are not mutually exclusive.

Majeed Dahiru, a public affairs analyst, writes from Abuja and can be reached through dahirumajeed@gmail.com.