Democracy & Governance

Severance Pay and Severe Pain -By Simon Kolawole

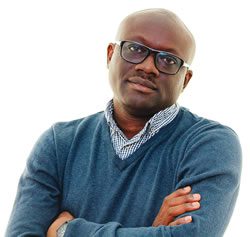

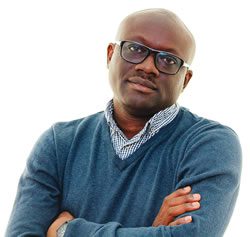

Simon Kolawole

For Mr. Mounir Gwarzo, director-general of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), these are not the nicest of times. He has just been suspended by Mrs Kemi Adeosun, minister of finance, over allegations of impropriety. Gwarzo was accused, among other things, of paying himself a “severance package” of N104,854,154 as a former executive commissioner — shortly after being named DG of the same commission. The argument is that since he was still serving in the same organisation, it was wrong for him to have collected the benefit. “Severance package” is theoretically a one-off exit payment for political appointees.

In other news, Gwarzo does not think his suspension has anything to do with the petition over severance pay. Reports here and there attribute the suspension to Gwarzo’s insistence on conducting a forensic audit of Oando Plc over allegations of insider abuses and irregularities. The forensic audit would have led to the suspension of the Oando management and the appointment of an interim management. Adeosun reportedly asked Gwarzo to impose fines on individual members of the management rather than carry out the audit, for which SEC has already engaged the services of Akintola Williams Deloitte.

Gwarzo was said to have objected, leading to a reportedly heated argument with the minister who allegedly seized the moment to remind him of the petition against him “pending since January”. The SEC DG requested that her directive be put in writing — to which Adeosun was said to have pointed out that she herself takes verbal instructions from President Muhammadu Buhari. Gwarzo left her office and wrote her on November 28, 2017, summarising the discussions at the meeting and asking again that the request be put in an official letter. He got a letter, dated November 29, 2017, quite all right, but it was to suspend him from office over the allegations against him.

The sequence of events and the circumstances would fit perfectly into the narrative that Adeosun decided to dig up the petition because Gwarzo continued to insist on the forensic audit, but the office of the minister has strongly denied the allegations. Oando Plc, understandably, has refused to join issues and would prefer to be left out of the picture. The oil company actually secured a court order to stop the forensic audit which it considers to be a witch hunt. In the final analysis, we are only left to work with rumours and speculations on what really transpired between the minister and the DG. Suspicion is not terribly helpful in this matter. It is neither here nor there.

My bigger interest is in the allegations against Gwarzo — that he got a mouth-watering severance package and that he awarded contracts to a company, Madusa Investments Ltd, in which he has interest. While confirming that he collected the N104 million pay-off in 2015, he denied any wrong doing, citing a board decision way back in 2002 which authorised the payment to DGs and commissioners who had served for a minimum of two years. He also said Madusa is a family business from which he had resigned his directorship when he was appointed a SEC commissioner in 2013. He denied that the company has done any job for, or received any payment, from SEC.

Now that he is being investigated, I think the anti-graft agencies are in a better position to prove or disprove the allegations of impropriety against him. This may sound funny, but we can say that since the ICPC and EFCC are also going to carry out their own “forensic audit” of Gwarzo, it is only proper to ask him to step aside while this is being done so that an interim manager can also be in place. The trouble, though, is that this may further complicate things for Oando and Adeosun — if the forensic audit of Oando does not go ahead eventually, it may prove too difficult to convince Nigerians that there is no truth in Gwarzo’s allegation. Fingers crossed.

My curiosity in this matter, lest I forget, is the legality of the severance pay. If indeed the board of SEC approved as far back as July 2002 — 11 years before Gwarzo became a commissioner — that the benefit should be paid to the DG and “permanent commissioners”, the suspended DG would have no case to answer. The quantum of the pay wouldn’t matter as long as there is no infraction involved. The real issue would be: was it legal or not? Are there documentations to prove it or not? However, if there was no such board decision and Gwarzo collected the benefit illegally, then he would have to keep a date with the hangman.

If he truly followed the letter of the law in collecting the pay-off, there are still more questions to ask — and in asking these questions, we will discover more loopholes in the law or policy, as the case may be. Should he have collected the benefit while still in service even if occupying a different office? It would mean that, technically, he is entitled to another severance pay after his current tenure since the processes of appointing an executive commissioner and DG are different. What this shows us clearly is that there is a lacuna in the policy. Those who made the policy did not take care of a situation where a commissioner is promoted DG after two years.

Gwarzo can even pursue a hypothetical argument — that if he serves as an executive commissioner at SEC for two years, doesn’t collect the severance benefit, gets appointed as the DG of another agency and is removed after one year, then he would have lost out on the benefit completely. On the other hand, if he forgoes the hefty package (let’s say out of “patriotism”) and gets appointed as a minister, his severance pay would be probably N5 million. Therefore, there was a higher incentive for him to quickly claim his benefit as a former SEC commissioner. There is a huge dichotomy between the benefits of a minister and the heads of “specialised agencies” serving under them.

There are loopholes in the way severance pay is defined and structured. I’m sure many public officers have been benefitting from this at federal, state and local levels. While you cannot punish or prosecute someone for what is legally permissible, you can fine-tune the law or policy to address the loopholes. I am, therefore, looking beyond Gwarzo in my argument. I am canvassing a comprehensive and standardised policy on severance pay such that everything will be clear to all. I guess this is the job of the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission and National Salaries, Incomes and Wages Commission. They should be the clearing houses for all such payments.

It gives me severe pains to know that there are some governors who, after getting a second term in office, pay themselves severance for their first term. That means they will collect a second severance pay after the second term, in addition to pension. I am also told that there are some legislators who get paid severance package at the end each term. So if they are re-elected five times, they get paid the benefit five times. I hope I am being misled — it is too bad to be true. We are also made to understand that some former governors who are now senators still collect pensions in addition to their hefty allowances in the national assembly. It may not be illegal but it is immoral.

To be clear, I have not declared Gwarzo culpable or not culpable. That is beyond my pay grade. Whether he is being punished over the Oando issue or over the petitions against him is beside the point. My worry, which I have managed to state clearly, is that we need to work on avoiding the lacuna in the severance benefits. This Gwarzo affair offers us an opportunity to streamline the payment of these benefits. I propose that an active public servant should be entitled to severance pay just once in a lifetime, preferably on final exit from government. That is more morally defensible, so let us standardise it — and legalise it.