Article of Faith

Peregrine: Religion, Techno-progressivism and African Emergence -By Leo Igwe

As the launch in India and the US have shown, attitudes are changing, especially in Europe, Asia, and America. Humans are developing and deploying technologies to exert powers beyond natural limits, to harness and harvest transcendence. Animals have become metaphors for these initiatives. The Peregrine Lander is an exercise in transnaturalism, in the transcendence of natural boundaries and powers.

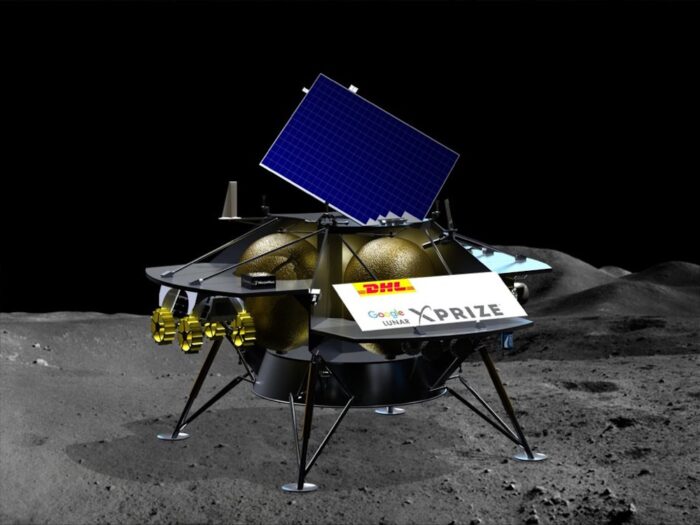

As I write this piece, Peregrine is on its way to the moon, and is scheduled to touch down on February 23, 2024. Peregrine is not a falcon, the fastest-flying bird in the world. No, it is a spacecraft named after the falcon. A Pittsburg-based company, Astrobotics Technology, developed the Peregrine lander. Today, January 8, a vehicle, the Vulcan Centaur rocket, which the United Launch Alliance, a joint venture by Boeing and Lockheed Martine developed, launched and got Peregrine on its way to the moon.

As in the case of the Indian space mission, the launch of the Peregrine lander has a lot of significance. It raises some transhumanist or transnaturalist issues that should disrupt and challenge thoughts and beliefs in Africa. As I noted in another piece, the Indian space mission to the Sun was named after the Sun god. Unlike many Africans, Indians did not resign to praying and worshipping Aditya. They went further, and forged technologies to harness and deliver transcendental thoughts, fantasies, and imaginaries associated with the Sun God. The Sun God ‘became’ an inspirer and ‘motivator’ of a space mission, some space invention and innovation beyond the deity as ‘religiously’ known and believed. They forged technologies to deliver the powers and essences of the Sun God. The same thing applies to this lunar lander. The lander illustrates transnatural thoughts, the technologization of imaginaries, and perceptions beyond the natural speed limits of Peregrine, the falcon.

In this case, Americans used the bird as a metaphor for a device that could fly to the moon, a machine that can, by moving at an extraordinary speed, get to this destination that the natural falcon cannot fly to. This mission again underscores the fact that the universe is not an object to be worshipped. Nature is not something to be ‘venerated’ but something to be explored and harnessed.

Nature is an object of study. The mysteries of the universe are not there to evoke fears and get us to endlessly kneel, pray, and supplicate. The mysteries are there to compel humans to invent and innovate ways and mechanisms to understand nature. The Sun and the moon exist not to be worshipped or divinized, but to be studied and explored. These celestial objects are travel destinations to behold, not abodes of deities. Incidentally, with limited knowledge, past generations of humans divinized and spiritualized these and other natural objects and forces. Hence we have the Sun God, the moon god, the river god or goddess, the god of thunder, the god of fertility and harvest etc. Earlier humans have related to them through worship, prayers, and ritual sacrifice of animals, sometimes of humans. They invested wild and strange animals with extraordinary powers and used worship and ritual sacrifice to make sense of their transcendental thinking and imaginations.

As the launch in India and the US have shown, attitudes are changing, especially in Europe, Asia, and America. Humans are developing and deploying technologies to exert powers beyond natural limits, to harness and harvest transcendence. Animals have become metaphors for these initiatives. The Peregrine Lander is an exercise in transnaturalism, in the transcendence of natural boundaries and powers.

For Africans, this project is replete with lessons and insights that could benefit the region. Africans need to know that living beings such as animals and insects can inspire inventions and innovations that transcend natural limits. That animals and insects can enable the production of technologies that serve the good of humanity. Many African societies associate certain animals with strange and extraordinary powers, including owls, snakes, cats, tortoises, and dogs. Too often, these animals are feared. People believe that they have occult powers. These animals are used for ritual sacrifice, to appease or placate the gods. The mindset that associates these animals with ritual powers is pervasive. Many Africans link bats, snakes, owls, and cats to witchcraft and harmful magic because they are told and brought up to believe that they are evil. Many Africans kill these animals anywhere they see them because they do not associate anything good and positive with these natural beings.

But as the Peregrine lander has shown, natural beings can inspire astounding technological innovations and programs that exceed and supersede the precincts of nature. Many Africans must begin to think in this direction and explore ways of turning their transcendental thoughts about these animals into technological feats. While there are Africans with transnational persuasion, concerns exist that Peregrine-like programs could elicit opposition from religious bodies. Religious and cultural groups may be unhappy with the initiative because they think that such programs offend their sensibilities or violate their sense of sacredness.

For instance, the Peregrine lander carries some cremated human remains for a lunar burial. The Navajo Nation, the largest group of Native Americans in the US, has complained that the moon held a sacred place in Navajo cosmology and allowing the remains to touch down on the moon was a form of desecration. Meanwhile those managing the project have rejected the claim, saying that the lunar burial was an act that adds to the sacredness of the moon, and a cause for celebration. The lunar burial invests the moon with a new layer of sacredness beyond the earth, beyond the limits of Peregrine as we know it. So these technological initiatives may generate hostile reactions from some segments of the society. And as in this case, those reactions should be thoughtfully and creatively managed.

Early in this 21st century, technologies promise real and profound changes. African emergence rests on transcendental thinking and the ability to use technologies to deliver these thoughts and realize social change. Religious and cultural concerns should not be allowed to undermine or jeopardize techno-progressivity, and the technologization of transcendental imaginaries in the region.

Leo Igwe holds a doctoral degree in religious studies and has a research interest in religion and transhumanism