Forgotten Dairies

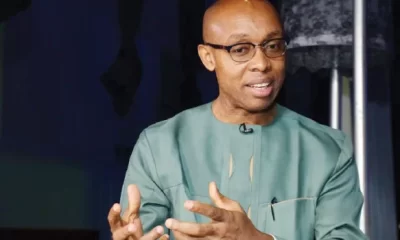

Still on Journalism and Patriotism in Nigeria -By Simon Kolawole

What is patriotism? The definition should be fairly straightforward: loving your country. One of my favourite all-time tunes is the 1988 song, “Nation and the People”, by The Mandators, with the refrain: “Love your country/Your nation and the people”. They sang passionately: “Some are trying to find solutions to all the problems we have/Some are trying to make it impossible for the problems to be solved.” The song progresses deeper philosophically: “Must you sell your father’s land for the love of this vanity now?” If I were to start a civic club for secondary school students in the country, this song would be the anthem. It is an immortal call to patriotism.

If patriotism were that simple to define, why should anyone doubt the loyalty of a journalist to his country when he warns that there is danger ahead and demands that the government should act swiftly and decisively to prevent a calamity? Having grown up and started my journalism career under military regimes in Nigeria, I got the impression at some point in my life that “patriotism” means to “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil”. That is, turn a blind eye to official impropriety. Journalists who report failings in the system are branded as “unpatriotic” by the state and marked for persecution. Till today, this official mindset has not changed.

I am bringing up the topic of “journalism and patriotism” today because of recent events in the land, particularly the resurgence of Boko Haram and the other security challenges. They are, again, highlighting the constant battles we journalists fight in the line of duty: the blackmail and the intimidation we have to deal with from the authorities, who hide under their nebulous definition of “patriotism”. The criteria are so narrow you are forced to wonder what exactly the role of a journalist should be. Is the journalist a thermometer — telling the society its “temperature” — or a thermostat — regulating the “temperature”? We must keep having this debate.

As an aside, I had an amusing experience recently. Sometime in 2017, a whopping fine of $6.5 billion plus $2.3 billion in interests was slammed on Nigeria by an arbitration tribunal in London, UK, in the case brought by P&ID over an alleged breach of contract. Immediately the news broke, I put my team at TheCable, the online newspaper I founded in 2014, on the alert. I asked them to dig up the details and draw out the implications “in the national interest”. The young guys got down to work. What they found out was disheartening: Nigeria had been handling the case nonchalantly. If we did not take critical steps, our foreign assets — forex reserves not excluded — would be jeopardised.

Personally, I was very disturbed. So I adopted a two-pronged approach: on the one hand, I got TheCable team to stay on the story, highlighting the implications and alerting the government and Nigerians to the looming danger; on the other hand, I leveraged on my contacts in government to push for urgent action because it appeared nobody was really worried about the case. Early this year, I spoke with the key government people I had access to, warning them that there was fire on the mountain and we must do everything to quench it, even if it meant sitting down with the P&ID guys to work out a much reasonable settlement. To me, $9.6 billion was murderous.

I would, on a good day, define that as “patriotism” if I was writing a dictionary. But you know what? In the last four weeks, at least three senior government officials have told me I have been classified as a “P&ID consultant”. They said I am “unpatriotic” because of the series of articles we did on the case. In my naivety, I thought the “unpatriotic” people were those who signed that kind of contract, those who failed to defend the country properly in the arbitration, and those did not apply for a review of the award within the 60-day grace in 2017. I didn’t know it was the person running around for a solution without collecting one kobo that would be classified as “unpatriotic”. So it goes.

As a journalist and columnist, I face all kinds of insults, accusations, blackmail and intimidation all the time. I consider them as part of the terms and conditions. If you can’t stand the heat, former US President Harry S. Truman said, get out of the kitchen. Nonetheless, only God knows how many people have been framed up, humiliated or harmed in this country based on spurious security reports, cheap conjectures and irrational suspicion. The danger, I should think, is that the feeble-minded will be coerced to “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil”. In fact, those with strong patriotic instincts will be forced at some point to ask themselves: “Who patriotism epp?”

Now, to the main focus today: how should the media report the Boko Haram resurgence? Despite claims that the terror group has been “degraded” or “technically defeated”, the reality is that we are still in trouble. Even President Muhammadu Buhari recently said Boko Haram acquires sophisticated weapons “with ease”. As journalists, are we supposed to continue to report only the victories recorded by the military and black out the blind sides? Is that patriotism? Would we really be helping our country? Can living in denial — as we are expected to do — solve any problem? No. It can only endanger us all. Returning the issue to the front burner is very critical. That’s patriotism.

I have a story to tell. Sometime in 2014, I was invited as a panellist to the Chief of Defence Staff Conference in Abuja. Air Chief Marshall Alex Badeh (late), then chief of defence staff, was there, with Air Marshall Adesola Amosu, then chief of air staff, Mr MD Abubakar, then inspector-general of police, and several other top security chiefs. I was not the lead speaker; I was just a discussant. But as soon as the officers realised I was a journalist, good God, they feasted on me like a hungry lion on bleeding meat. They did not even bother to ask the lead speaker any questions. All questions were directed at me. That day, I bore all the sins of Nigerian journalists. I was a sorry sight.

What was the issue? One military officer after the other said Nigerian journalists were “unpatriotic” because of the reports coming from the warfront in the north-east. They said we were enemies of Nigeria. The military was winning the war, they said, but we were painting a different picture to Nigerians. At gunpoint, I still raised the issue of the welfare of soldiers: how they were eating cold lunch and sour dinner, how they were being given only three sachets of pure water per day in the hellish heat of Maiduguri, how they had no sleeping kits and how they were battle-weary and suffering from PTSD — in addition to poor equipment to confront the more sophisticated insurgents.

The way the officers dismissed the issues put the fear of God in me afresh. One service chief said: “There is nothing wrong with the soldiers sacrificing a little comfort in war front… we did not send them there to be eating fried eggs and baked beans.” When he left office, he was arranged in court by the EFCC for an alleged fraud running into billions — the money meant for the soldiers welfare. He was preaching sacrifice at the conference! Another chief was said to have helped himself with billions while our soldiers were being killed like rats. Boko Haram soon overran three states and starting attacking Abuja and Kano with ease. We were supposed to report that all was well.

The question is: who is unpatriotic? Is it the journalists that were reporting the true situation in the north-east or the security chiefs that were lying to their commander-in-chief while diverting funds meant for operation? In their warped definition, the security chiefs were the “patriots” for painting a false picture — while the saboteurs/traitors were the journalists who reported that a false picture was being painted. General Martin Agwai, former chief of defence staff, came to my rescue that day. He said having spent 37 years in uniform and lived as a civilian for five years then, he could empathise with both sides. It is not simple black and white, he said. I started breathing again.

Before Agwai intervention, the police chief had accused Nigerian journalists of not putting the country first. He said he was in Atlanta, where CNN is based, shortly before the conference. He said robbery goes on in Atlanta but CNN will not report it. Of course, he was incorrect. I watch CNN regularly and they report robbery, murder and mass shooting. BBC reports knife attacks in London and rolls out latest murder statistics. By his logic, we should not be reporting the cases of kidnappings in the country. We should pretend everywhere is safe so that many more Nigerians will walk into the hands of the kidnappers! Is that patriotism? We need to seriously debate this.

In the final analysis, I would argue that journalists should serve the cause of patriotism — but not as defined by the state actors. There is a space for responsibility and restrain, no doubt; in fact, there are situations that require a journalist to be both a thermometer and a thermostat. It is not black or white. You can accuse Nigerian journalists of being sensational and insensitive at times and that would be in order, but that is a topic for another day. It is patriotism we are discussing here. Certainly, a journalist’s perspective may never be acceptable to state actors. Painting a false picture, or hiding the real picture, can end up hurting the country. That cannot be patriotism — for sure.